Ahiram sarcophagus

The Ahiram sarcophagus (also spelled Ahirom, 𐤀𐤇𐤓𐤌 in Phoenician) was the sarcophagus of a Phoenician king of Byblos (c. 850 BC),[1][2] discovered in 1923 by the French excavator Pierre Montet in tomb V of the royal necropolis of Byblos. Ahirom is not attested in any other Ancient Oriental source, although some scholars have suggested a possible connection to the contemporary King Hiram mentioned in the Hebrew Bible (see Hiram I).

| Ahiram sarcophagus | |

|---|---|

The Sarcophagus of Ahiram in its current location (Lebanon). | |

| Material | Limestone |

| Writing | Phoenician language |

| Created | c. 850 BC |

| Discovered | 1923 |

| Present location | National Museum of Beirut |

| Identification | KAI 1 |

The sarcophagus is famed for its bas relief carvings, and its Phoenician language inscription. One of five known Byblian royal inscriptions, the inscription is considered to be the earliest known example of the fully developed Phoenician alphabet.[3] For some scholars it represents the terminus post quem of the transmission of the alphabet to Europe.[3]

Discovery

The sarcophagus was found following a landslide in the cliffs surrounding Byblos (in now modern-day Lebanon) in late 1923, which revealed a number of Phoenician royal tombs. The tomb of Ahirom was ten metres deep.[4][5][6]

Sarcophagus

The sarcophagus of Ahiram was discovered by the French archaeologist Pierre Montet in 1923[7] in Byblos.[8] Its low relief carved panels make it "the major artistic document for the Early Iron Age" in Phoenicia.[9] Associated items dating to the Late Bronze Age either support an early dating, in the 13th century BC or attest the reuse of an early shaft tomb in the 11th century BC.

The major scene represents a king seated on a throne carved with winged sphinxes. A priestess offers him a lotus flower. On the lid two male figures face one another with seated lions between them. These figures have been interpreted by Glenn Markoe as representing the father and son of the inscription. The rendering of figures and the design of the throne and a table show strong Assyrian influences.[9] A total absence of Egyptian objects of the 20th and 21st dynasties in Phoenicia[10] contrasts sharply with the resumption of Phoenician-Egyptian ties in the 22nd Dynasty of Egypt.[11]

Inscriptions

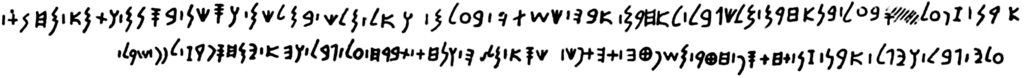

An inscription of 38 words is found on parts of the rim and the lid of the sarcophagus. It is written in the Old Phoenician dialect of Byblos and is the oldest witness to the Phoenician alphabet of considerable length discovered to date:[12]

According to the recent re-edition of the Ahirom inscriptions and a some years later new reconstruction of a lacuna within the inscription (both by Reinhard G. Lehmann,[13][14]) the translation of the sarcophagus inscription reads:

A coffin made it [Pil]sibaal, son of Ahirom, king of Byblos, for Ahirom, his father, lo, thus he put him in seclusion. Now, if a king among kings and a governor among governors and a commander of an army should come up against Byblos; and when he then uncovers this coffin – (then:) may strip off the sceptre of his judiciary, may be overturned the throne of his kingdom, and peace and quiet may flee from Byblos. And as for him, one should cancel his registration concerning the libation tube of the memorial sacrifice.

The formulas of the inscription were immediately recognised as literary in nature, and the assured cutting of the archaic letters suggested to Charles Torrey[7] a form of writing already in common use. A 10th-century BC date for the inscription has become widely accepted.

Halfway down the burial shaft another short inscription was found incised at the southern wall. It had been first published as a warning to an excavator not to proceed further,[15] but now is understood as part of some initiation ritual which remains unknown in detail.[16] It reads:

Concerning knowledge:

here and now be humble (you yourself!)

‹in› this basement!"

King Ahiram

Ahiram himself is not entitled a king, neither of Byblos nor of any other city state. It is said that he was succeeded by his son Ithobaal I who is the first to be explicitly entitled King of Byblos,[17] which is due to an old misreading of a text lacuna. According to a new reconstruction of the lacuna the name of Ahiram's son is to be read [Pil]sibaal, and the reading Ithobaal should be disregarded.[14] The early king list of Byblos is again subject to further study.

Literature

- Pierre Montet: Byblos et l'Egypte, Quatre Campagnes des Fouilles 1921-1924, Paris 1928 (reprint Beirut 1998: ISBN 2-913330-02-2)): 228–238, Tafel CXXVII-CXLI

- Ellen Rehm: Der Ahiram-Sarkophag, Mainz 2004 (Forschungen zur phönizisch-punischen und zyprischen Plastik, hg. von Renate Bol, II.1. Dynastensarkophage mit szenischen Reliefs aus Byblos und Zypern Teil 1.1)

- Reinhard G. Lehmann: Die Inschrift(en) des Ahirom-Sarkophags und die Schachtinschrift des Grabes V in Jbeil (Byblos), Mainz 2005 (Forschungen zur phönizisch-punischen und zyprischen Plastik, hg. von Renate Bol, II.1. Dynastensarkophage mit szenischen Reliefs aus Byblos und Zypern Teil 1.2)

- Jean-Pierre Thiollet: Je m'appelle Byblos. Paris 2005. ISBN 2-914-26604-9

- Michael Browning "Scholar updates translation of ancient inscription", in: The Palm Beach Post, Sunday, July 3, 2005 p. 17A.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Category:Sarcophagus of Ahiram. |

- Reinhard G. Lehmann: Wer war Aḥīrōms Sohn (KAI 1:1)? Eine kalligraphisch-prosopographische Annäherung an eine epigraphisch offene Frage, in: V. Golinets, H. Jenni, H.-P. Mathys und S. Sarasin (Hg.), Neue Beiträge zur Semitistik. Fünftes Treffen der ArbeitsgemeinschaftSemitistik in der Deutschen MorgenländischenGesellschaft vom 15.–17. Februar 2012 an der Universität Basel (AOAT 425), Münster: Ugarit-Verlag 2015, pp. 163-180

External links

- Press release on new deciphering and translation (in German)

References

- Finkelstein, Israel (2016). "The swan-song of Proto-Canaanite in the ninth century BCE in light of an alphabetic inscription from Megiddo".

- The date remains the subject of controversy, according to Glenn E. Markoe, "The Emergence of Phoenician Art" Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research No. 279 (August 1990):13-26) p. 13. "Most scholars have taken the Ahiram inscription to date from around 1000 B.C.E.", notes Edward M. Cook, "On the Linguistic Dating of the Phoenician Ahiram Inscription (KAI 1)", Journal of Near Eastern Studies 53.1 (January 1994:33-36) p. 33 JSTOR. Cook analyses and dismisses the date in the thirteenth century adopted by C. Garbini, "Sulla datazione della'inscrizione di Ahiram", Annali (Istituto Universitario Orientale, Naples) 37 (1977:81-89), which was the prime source for early dating urged in Bernal, Martin (1990). Cadmean Letters: The Transmission of the Alphabet to the Aegean and further West before 1400 BC. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 0-931464-47-1. Arguments for a mid-9th to 8th century BC date for the sarcophagus reliefs themselves—and hence the inscription, too—were made on the basis of comparative art history and archaeology by Edith Porada, "Notes on the Sarcophagus of Ahiram," Journal of the Ancient Near East Society 5 (1973:354-72); and on the basis of paleography among other points by Ronald Wallenfels, "Redating the Byblian Inscriptions," Journal of the Ancient Near East Society 15 (1983:79-118).

- Cook, p1

- René Cagnat, Nouvelles Archéologiques, Syria 4 (1923): 334–344

- Pierre Montet, "Les fouilles de Byblos en 1923," L’Illustration 3 (May 3, 1924), 402–405.

- Calligraphy and Craftsmanship in the Ahirom inscription. Considerations on skilled linear flat writing in early first millennium Byblos, Reinhard G. Lehmann

- Torrey, Charles C. (1925). "The Ahiram Inscription of Byblos". Journal of the American Oriental Society. Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 45. 45: 269–279. doi:10.2307/593505. JSTOR 593505.

- Pritchard, James B. (1968). Archaeology and the Old Testament. Princeton: Univ. Press.; Moscati, Sabatino (2001). The Phoenicians. London: Tauris. ISBN 1-85043-533-2.;

- Markoe, Glenn E. (1990). "The Emergence of Phoenician Art". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 279 (279): 13–26. doi:10.2307/1357205. JSTOR 1357205. [pp. 13, 19-22]

- J. Leclant, "Les relations entre l'Égypte et la Phénicie du voyage de Ounamon à l'expédition d'Alexandre", in The role of the Phoenicians in the Interaction of Mediterranean Civilisations, W. Ward, ed. (Beirut: American University) 1968:11.

- For a recent discussion under aspects of aert history, see Ellen Rehm: Der Ahiram-Sarkophag, Mainz 2004 (Forschungen zur phönizisch-punischen und zyprischen Plastik, hg. von Renate Bol, II.1. Dynastensarkophage mit szenischen Reliefs aus Byblos und Zypern Teil 1.1)

- The most recent scholarly book which deals with all aspects of the inscription is Reinhard G. Lehmann, Die Inschrift(en) des Ahirom-Sarkophags und die Schachtinschrift des Grabes V in Jbeil (Byblos), (Mainz), 2005 (Forschungen zur phönizisch-punischen und zyprischen Plastik, hg. von Renate Bol, II.1. Dynastensarkophage mit szenischen Reliefs aus Byblos und Zypern Teil 1.2)

- Reinhard G. Lehmann: Die Inschrift(en) des Ahirom-Sarkophags und die Schachtinschrift des Grabes V in Jbeil (Byblos), 2005, p. 38

- Reinhard G. Lehmann, Wer war Aḥīrōms Sohn (KAI 1:1)? Eine kalligraphisch-prosopographische Annäherung an eine epigraphisch offene Frage, in: V. Golinets, H. Jenni, H.-P. Mathys und S. Sarasin (Hg.), Neue Beiträge zur Semitistik. Fünftes Treffen der ArbeitsgemeinschaftSemitistik in der Deutschen MorgenländischenGesellschaft vom 15.–17. Februar 2012 an der Universität Basel (AOAT 425), Münster: Ugarit-Verlag 2015, pp. 163-180

- by René Dussaud, in Syria 5 (1924:135-57).

- Reinhard G. Lehmann: Die Inschrift(en) des Ahirom-Sarkophags und die Schachtinschrift des Grabes V in Jbeil (Byblos), 2005, p. 39-53

- Vance, Donald R. (1994). "Literary Sources for the History of Palestine and Syria: The Phœnician Inscriptions". The Biblical Archaeologist. The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 57, No. 1. 57 (1): 2–19. doi:10.2307/3210392. JSTOR 3210392.