Story of Ahikar

The Story of Ahiqar, also known as the Words of Ahikar, is a story first attested in Aramaic from the fifth century BCE that circulated widely in the Middle and Near East. It has been characterised as "one of the earliest 'international books' of world literature".[1]

The principal character is the Aramean Ahiqar (Aramaic: אחיקר, also transliterated as Aḥiqar, Arabic Hayqar, Greek Achiacharos and variants on this theme such as Armenian: Խիկար Xikar), a sage known in the ancient Near East for his outstanding wisdom.

Origins and development

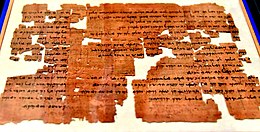

At Uruk, a Cuneiform text has been found including the name Ahuqar, suggesting that Ahikar was a historical figure around the seventh century BCE.[2] However, the story as it is now known is thought to have originated in Aramaic in Mesopotamia, probably around the late seventh or early sixth century BCE.[3] The first attestation is a papyrus fragment of the fifth century BCE from the ruins of Elephantine.[4] The narrative of the initial part of the story is expanded greatly by the presence of a large number of wise sayings and proverbs that Ahikar is portrayed as speaking to his nephew. It is suspected by most scholars that these sayings and proverbs were originally a separate document, as they do not mention Ahikar. Some of the sayings are similar to parts of the Biblical Book of Proverbs, others to the deuterocanonical Wisdom of Sirach, and others still to Babylonian and Persian proverbs. The collection of sayings is in essence a selection from those common in the Middle East at the time.

There are references in Romanian, Slavonic, Armenian, Arabic and Syriac literature to a legend, of which the hero is Ahikar. It was pointed out by scholar George Hoffmann in 1880 that this Ahikar and the Achiacharus of Tobit are identical. It has been contended that there are traces of the legend even in the New Testament, and there is a striking similarity between it and the Life of Aesop by Maximus Planudes (ch. xxiii–xxxii). An eastern sage Achaicarus is mentioned by Strabo.[5] It would seem, therefore, that the legend was undoubtedly oriental in origin, though the relationship of the various versions can scarcely be recovered.[6]

British classicist Stephanie West has argued that the story of Croesus in Herodotus as an adviser to Cyrus I is another manifestation of the Ahikar story.[7]

Narrative

In the story, Ahikar was chancellor to the Assyrian kings Sennacherib and Esarhaddon. Having no child of his own, he adopted his nephew Nadab/Nadin, and raised him to be his successor. Nadab/Nadin ungratefully plotted to have his elderly uncle murdered, and persuades Esarhaddon that Ahikar has committed treason. Esarhaddon orders Ahikar be executed in response, and so Ahikar is arrested and imprisoned to await punishment. However, Ahikar reminds the executioner that the executioner had been saved by Ahikar from a similar fate under Sennacherib, and so the executioner kills a prisoner instead, and pretends to Esarhaddon that it is the body of Ahikar.

The remainder of the early texts do not survive beyond this point, but it is thought probable that the original ending had Nadab/Nadin being executed while Ahikar is rehabilitated. Later texts portray Ahikar coming out of hiding to counsel the Egyptian king on behalf of Esarhaddon, and then returning in triumph to Esarhaddon. In the later texts, after Ahikar's return, he meets Nadab/Nadin and is very angry with him, and Nadab/Nadin then dies.

Book of Tobit

In the Book of Tobit (second or third century BCE), Ahikar appears as Tobit's nephew, in royal service at Nineveh and, in the summary of W. C. Kaiser, Jr.,

'chief cupbearer, keeper of the signet, and in charge of administrations of the accounts under King Sennacherib of Assyria', and later under Esarhaddon (Tob. 1:21–22 NRSV). When Tobit lost his sight, Ahikar took care of him for two years. Ahikar and his nephew Nadab were present at the wedding of Tobit's son, Tobias (2:10; 11:18). Shortly before his death, Tobit said to his son: 'See, my son, what Nadab did to Ahikar who had reared him. Was he not, while still alive, brought down into the earth? For God repaid him to his face for this shameful treatment. Ahikar came out into the light, but Nadab went into the eternal darkness, because he tried to kill Ahikar. Because he gave alms, Ahikar escaped the fatal trap that Nadab had set for him, but Nadab fell into it himself, and was destroyed' (14:10 NRSV).[8]

Note however that the Greek does not have "Ahikar" or "Nadab" in these verses, but "Αχιαχαρος" (Achiacharus in KJV), "Νασβας" (Nasbas in KJV) in 11:18, and "Αμαν" (Aman in KJV) in 14:10.[9]

Editions and translations

- The Story of Aḥiḳar from the Aramaic, Syriac, Arabic, Armenian, Ethiopic, Old Turkish, Greek and Slavonic Versions, ed. by F. C. Conybeare, J. Rendel Harris and Agnes Smith Lewis, 2nd edn (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1913), available at archive.org

- Platt, Rutherford H., Jr., ed. (1926). The forgotten books of Eden. New York, NY: Alpha House. p. 198–219. (audiobook)

- The Say of Haykar the Sage translated by Richard Francis Burton

Citations

- Ioannis M. Konstantakos, 'A Passage to Egypt: Aesop, the Priests of Heliopolis and the Riddle of the Year (Vita Aesopi 119–120)', Trends in Classics, 3 (2011), 83–112 (p. 84), DOI 10.515/tcs.2011.005.

- W. C. Kaiser, Kr., 'Ahikar uh-hi’kahr', in The Zondervan Encyclopedia of the Bible, ed. by Merrill C. Tenney, rev. edn by Moisés Silva, 5 vols (Zondervan, 2009), s.v.

- Ioannis M. Konstantakos, 'A Passage to Egypt: Aesop, the Priests of Heliopolis and the Riddle of the Year (Vita Aesopi 119–120)', Trends in Classics, 3 (2011), 83–112 (p. 84), DOI 10.515/tcs.2011.005.

- W. C. Kaiser, Kr., 'Ahikar uh-hi’kahr', in The Zondervan Encyclopedia of the Bible, ed. by Merrill C. Tenney, rev. edn by Moisés Silva, 5 vols (Zondervan, 2009), s.v.

- Strabo, Geographica 16.2.39: "...παρὰ δὲ τοῖς Βοσπορηνοῖς Ἀχαΐκαρος..."

-

- "Croesus' Second Reprieve and Other Tales of the Persian Court," Classical Quarterly (n.s.) 53 (2003): 416–437.

- W. C. Kaiser, Kr., 'Ahikar uh-hi’kahr', in The Zondervan Encyclopedia of the Bible, ed. by Merrill C. Tenney, rev. edn by Moisés Silva, 5 vols (Zondervan, 2009), s.v.

- See Tobit in Wikisource.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Story of Ahikar |