Agnes Ballard

Agnes Ballard (September 14, 1877 – November 24, 1969) was an American architect and educator. She was the first female registered architect in Florida, the sixth woman admitted to the American Institute of Architects and the first from Florida. As an educator, she taught geography, biology, chemistry, Latin and mathematics in West Palm Beach, Florida. Ballard was also one of the first women to be elected to a public office in Florida, serving as Superintendent of Public Education for Palm Beach County, Florida for four years.

Agnes Ballard | |

|---|---|

Ballard in 1920 | |

| Born | September 14, 1877 |

| Died | November 24, 1969 (aged 92) |

| Occupation | Architect, educator |

| Years active | 1906–1957 |

Biography

Agnes Ballard was born in Oxford, Massachusetts, on September 14, 1877,[1][2] the daughter of Dana L. Ballard and Jane R. Carpenter, both originally from Vermont.[3] She attended public schools in Worcester, Massachusetts,[1] and went on to attend Wellesley College in 1902.[4] She graduated from Worcester Normal School (a teacher training college) in 1905.[2][5]

Early teaching career

Seeking a challenge after graduation she took a teaching job in Palmer, Michigan, but found she disliked the cold weather there. "I saw so much snow In one season I wanted to go somewhere where I never would see snow again."[1] So, in 1906, at age 29[6], she moved to West Palm Beach, Florida, where she got a job teaching geography, biology and chemistry at Palm Beach High School.[1] In 1908, she moved to a nearby private school opened by Grace Lainhart, where she taught Latin and mathematics.[1]

Seeking a higher salary, she again moved north in 1910, this time to White Plains, New York, but again found the snow was not for her. She returned to Florida to teach in St. Augustine. She moved north once more when she became a private secretary (for the local YWCA, and then an Episcopal church) in La Crosse, Wisconsin. She would soon return to Florida for good, but this time not as a teacher.[1]

Switch to architecture

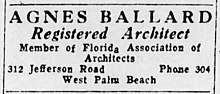

During her time in La Crosse, she had apprenticed at the architectural firm of Percy Dwight Bentley.[7][8] In 1913, she returned to Florida and continued to study architecture.[1] In 1914, she was granted architecture license No. 6 by the State of Florida.[9] She was not only the first woman to be a licensed architect in the state,[10] but she received the first license beyond those the five-member licensing board in Tallahassee issued to themselves.[1] In 1916, she became only the sixth woman to be granted membership in the American Institute of Architects.[7] She ran an ad in the local city directory and became a regular fixture in the local society column.[11]

When she started as an architect, she used her home as an office and studio[12] for her one-woman practice.[6] Asked about her architecture projects, she said she had worked on "apartments, residences and hot dog stands."[1] She became acquainted with fellow architect Addison Mizner, who designed lavish homes in the area. When he organized a local architects' club, Ballard was the secretary.[1]

Superintendent of schools

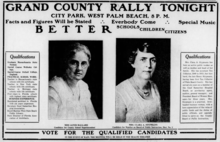

After the 19th Amendment was adopted on August 18, 1920, friends asked Ballard to run for office in the election that fall. She ran for County Superintendent of Schools, alongside Clara Stypmann who ran for the school board.[1] Ballard had worked as a teacher for the school district before, but her six years of architecture experience was also relevant because the district was booming and needed to build new schools.[4] Both candidates won their elections,[5] making them among the first women ever elected to public office in Florida.[13] Ballard took office on January 4, 1921.[4][5]

During her term, Ballard led the district through "boom years of incredible growth."[12][6] She was appointed chairperson of the civic improvement committee of the Florida Association of Architects.[10] Among the building projects that were begun under her was a vocational school at Canal Point, built for the then large sum of $8,000.[4] She was elected President of the Royal Palm Educational Association, an alliance of the school districts of three Florida counties.[5]

But she was a "stern" leader and her term of office was a "rocky one." She sought bond money to build new schools, but local voters were unenthusiastic. As a result she proposed the district buy an early version of a portable classroom. She once fired a male principal who had his students demonstrate at her home until police were called.[6]

In 1924, she had "had enough"[1] and declined to run for re-election. Joseph A. Youngblood took over her post.[5]

Later career

After her term ended, Ballard got into real estate investing and did well until a crash occurred in 1926.[1] That sent her back to teaching and architecture.[1][5]

She contacted Youngblood (her successor) for a teaching job, and she was given one at Conniston Road School.[5] By 1934, she was teaching Latin, algebra, history, English and civics at Palm Beach Elementary.[1] She continued her education during the summer in Gainesville, Florida, and, in August 1936,[14] the University of Florida awarded her a B.A. in Education.[1][4] She made Phi Kappa Phi.[14]

In 1947, she retired from teaching after 19 years of service,[4] taking up architecture again. At this time, she had two draftsmen working for her.[1] In 1957, she retired from her architecture business[1] and again ran for school board, this time at age 80, but failed in this attempt.[5]

After a local article chronicled her forgotten history,[6] the Florida chapter of the American Institute of Architects voted to give her a posthumous award in July 2016.[15]

Personal life

Ballard never married.[9] She had one brother (Willis D.)[16] and one sister (Ethel G.),[17] both of whom she survived.[9] Aside from English and Latin, she spoke five languages[6] including French, Spanish, Italian, German and Russian.[9] She sang and played the organ; she played chess.[9] She was involved in many clubs and other activities, to the extent that her friends called her "Activity" Ballard.[6] She occasionally travelled, visiting England and Scotland in 1908.[1] She also took a trip to Europe in 1926,[5] visiting Paris and the French Riviera.[1] Later in life she visited Alaska on the recommendation of Wilson Mizner (the brother of architect Addison Mizner).[1]

She died on November 24, 1969, in West Palm Beach.[9]

Known architectural works

Many of Ballard's architectural works have not survived to the present day, or are not recorded as being hers.[6] Some that are known to still exist:

- 411 26th Street (1951), a non-contributing property in the Old Northwood Historic District in West Palm Beach[5][15]

- Palm Beach house (1953), renovated by sculptor John Raimondi in 1988[18]

- Lund House (1955) at 3410 Poinsettia Ave, West Palm Beach[19]

See also

- Ida Annah Ryan, the second woman AIA from Florida, also born in Massachusetts

- Marion Manley, the third woman AIA from Florida and the first woman FAIA from the state

- Women in architecture

References

- Ledden, Jack (December 7, 1958). "Off the Cuff". The Palm Beach Post. p. 4. Archived from the original on November 11, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- King, Leone (September 15, 1963). "Miss Ballard Scores In 80's Today... Palm Beach Notes". The Palm Beach Post. p. 7. Archived from the original on November 11, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ""Massachusetts Births, 1841-1915," database with images". FamilySearch. March 11, 2018. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

Agnes Ballard, 14 Sep 1877, Oxford, Massachusetts; citing reference ID #952, Massachusetts Archives, Boston; FHL microfilm 1,428,170.

- Benjamin, Gentry (July 7, 1991). "Woman Led '20s Boom In District". Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on 2017-05-13. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- Pedersen, Ginger (July 27, 2014). "The Rediscovery of Agnes Ballard". Boynton Beach Historical Society. Archived from the original on May 12, 2017. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- Marshall, Barbara (July 8, 2016). "Palm Beach County woman was political trailblazer long before Hillary". The Palm Beach Post. Archived from the original on 2017-05-13. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- Allaback, Sarah (2008). The First American Women Architects. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. pp. 9, 237. ISBN 9780252033216. OCLC 167518574. Retrieved May 12, 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Boudreau, Richard. "Percy Dwight Bentley (1885-1968)". National Attention: Local Connection La Crosse’s contributions to the Arts and Entertainment in America (PDF). pp. 31–33. Retrieved October 16, 2018.

- Lewis, Beryl B. (November 25, 1969). "Miss Agnes Ballard, Architect, Educator". The Palm Beach Post. p. 27. Archived from the original on October 16, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Miss Agnes Ballard Given Appointment - Palm Beach Woman Is Head Of Civic Committee of Florida Architects". Miami Daily Metropolis. July 7, 1921. p. 22. Archived from the original on November 11, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

Miss Ballard was the sixth architect in Florida to receive a certificate of registration and the first woman to receive such a certificate.

- Tuckwood, Jan (November 9, 2016). "Clinton's defeat does not mar women's progress in Palm Beach County". The Palm Beach Post. Archived from the original on 2017-05-13. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- DeVries, Janet M.; L P. Ginger (2015). Legendary Locals of West Palm Beach. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781439653883. OCLC 968040919.

- "Numerous Florida Women Are Holding Public Office". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. February 22, 1946. p. 8. Archived from the original on November 9, 2018. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

The first Florida woman elected to office - although there were many appointments prior to that was Miss Agnes Ballard, who was chosen Palm Beach county superintendent of public instruction in 1924 [sic]

- "U-F Graduates to Hear Pepper". Sarasota Herald. August 28, 1936. p. 6. Archived from the original on November 9, 2018. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

Students making phi kappa phi, highest scholastic fraternity, are as follows: Agnes Ballard, West Palm Beach...

- Marshall, Barbara (July 14, 2016). "Forgotten female leader to be honored, thanks to Palm Beach Post story". The Palm Beach Post. Archived from the original on 2017-05-13. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- "Deaths And Funerals - Ballard, Col. Willis D." The Palm Beach Post. July 1, 1950. p. 4. Archived from the original on November 11, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ""United States Census, 1900," database with images". FamilySearch. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

Agnes Ballard in household of Dana Ballard, Precinct 2 Worcester city Ward 6, Worcester, Massachusetts, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) 1760, sheet 2A, family 37, NARA microfilm publication T623 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1972.); FHL microfilm 1,240,697.

- Savage, Brenda (December 7, 1988). "Artist Sculpts New Design For Old PB Home". Palm Beach Daily News. pp. 8, 4. Archived from the original on November 11, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

Originally encompassing some 1,500 square feet, the home was designed by architect Agnes Ballard in 1953. "She did many cement block structure homes in Palm Beach," Raimondi said. "She was a school teacher. Developers would buy a tract of land here and hire her to do 10 houses at a time. This was during a time when women architects were not considered serious. But she was designing small, functional houses that are open and airy to catch the cross breezes. Her designs are structurally sound."

- Burket, Ella Margaret (January 8, 1956). "Ultra Marine Motif Rule Honeymoon Cottage Colors". The Palm Beach Post-Times. XII (51). p. 27. Archived from the original on November 11, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.