Agitprop

Agitprop (/ˈædʒɪtprɒp/;[1][2][3] from Russian: агитпроп, tr. Agitpróp, portmanteau of agitatsiya, "agitation" and propaganda, "propaganda")[4] is political propaganda, especially the communist propaganda used in Soviet Russia, that is spread to the general public through popular media such as literature, plays, pamphlets, films, and other art forms with an explicitly political message.[5]

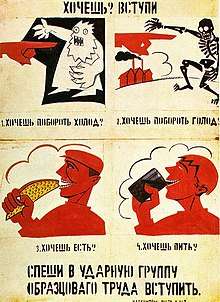

"1. You want to overcome cold?

2. You want to overcome hunger?

3. You want to eat?

4. You want to drink?

Hasten to join shock brigades of exemplary labor!"

The term originated in Soviet Russia as a shortened name for the Department for Agitation and Propaganda (отдел агитации и пропаганды, otdel agitatsii i propagandy), which was part of the central and regional committees of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.[6] Within the party apparatus, both agitation (work among people who were not Communists) and propaganda (political work among party members) were the responsibility of the agitpropotdel, or APPO. Its head was a member of the MK secretariat, although he or she ranked second to the head of the orgraspredotdel.[7] Typically Russian agitprop explained the ideology and policies of the Communist Party and attempted to persuade the general public to support and join the party and share its ideals. Agitprop was also used for dissemination of information and knowledge to the people, like new methods of agriculture. After the October Revolution of 1917, an agitprop train toured the country, with artists and actors performing simple plays and broadcasting propaganda.[8] It had a printing press on board the train to allow posters to be reproduced and thrown out of the windows as it passed through villages.[9]

It gave rise to agitprop theatre, a highly politicized theatre that originated in 1920s Europe and spread to the United States; the plays of Bertolt Brecht are a notable example.[10] Russian agitprop theater was noted for its cardboard characters of perfect virtue and complete evil, and its coarse ridicule.[11] Gradually the term agitprop came to describe any kind of highly politicized art.

Forms

During Russian Civil War agitprop took various forms:

- Use of the press: Bolshevik strategy from the beginning was to gain access to the primary medium of dissemination of information in Russia: the press.[12] The socialist newspaper Pravda resurfaced in 1917 after being shut down by the Tsarist censorship three years earlier. Prominent Bolsheviks like Kamenev, Stalin and Bukharin became editors of Pravda during and after the revolution, making it an organ for Bolshevik agitprop. With the decrease in popularity and power of Tsarist and Bourgeois press outlets, Pravda was able to become the dominant source of written information for the population in regions controlled by the Red Army .[13]

- Oral-agitation networks: The Bolshevik leadership understood that to build a lasting regime, they would need to win the support of the mass population of Russian peasants. To do this, Lenin organized a Communist party that attracted demobilized soldiers and others to become supporters of the Bolshevik ideology, dressed up in uniforms and sent to travel the countryside as agitators to the peasants.[14] The oral-agitation networks established a presence in the isolated rural areas of Russia, expanding Communist power.

- Agitational trains and ships: To expand the reach of the oral-agitation networks, the Bolsheviks pioneered using modern transportation to reach deeper into Russia. The trains and ships carried agitators armed with leaflets, posters and other various forms of agitprop. Train cars included a garage of motorcycles and cars in order for propaganda materials to reach the rural towns not located near rail lines. The agitational trains expanded the reach of agitators into Eastern Europe, and allowed for the establishment of agitprop stations, consisting of libraries of propaganda material. The trains were also equipped with radios, and their own printing press, so they could report to Moscow the political climate of the given region, and receive instruction on how to custom print propaganda on the spot to better take advantage of the situation.[15]

- Literacy campaign: The peasant society of Russia in 1917 was largely illiterate making it difficult to reach them through printed agitprop. The People's Commissariat of Enlightenment was established to spearhead the war on illiteracy.[16] Instructors were trained in 1919, and sent to the countryside to create more instructors and expand the operation into a network of literacy centers. New textbooks were created, explaining Bolshevik ideology to the newly literate members of Soviet society, and the literacy training in the army was expanded.[17]

See also

- Agit-train

- Blue Blouse

- Propaganda in the Soviet Union

- Left Column (theater troupe)

- Russian Telegraph Agency (ROSTA)

Literature

- The Soviet Propaganda Machine, Martin Ebon, McGraw-Hill 1987, ISBN 0-07-018862-9

- Rusnock, K. A. (2003). "Agitprop". In Millar, James (ed.). Encyclopedia of Russian History. Gale Group, Inc. ISBN 0-02-865693-8.

- Vellikkeel Raghavan (2009). Agitation Propaganda Theatre. Chandigarh: Unistar Books. ISBN 81-7142-917-3.

References

- Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- "agitprop". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- "agitprop(n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica Article (July 11, 2002). "agitprop". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- "Agitprop". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Merridale, Catherine (1990). Moscow Politics and the Rise of Stalin. London: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 142. ISBN 978-1-349-21044-2. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "Agitprop Train". YouTube. 2007-06-15. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- Paul A. Smith, On Political War, p. 124, National Defense University Press, 1989

- Richard Bodek (1998) "Proletarian Performance in Weimar Berlin: Agitprop, Chorus, and Brecht", ISBN 1-57113-126-4

- Richard Pipes, Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime, p. 303, ISBN 978-0-394-50242-7

- Kenez, pp. 5–7

- Kenez, pp. 29-31

- Kenez, pp. 51-53

- Kenez, p. 59.

- Kenez, p. 74

- Kenez, pp. 77-78

Sources

- Schütz, Gertrud (1988). Kleines Politisches Wörterbuch. Berlin: Dietz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-320-01177-2.

- Kenez, Peter (November 29, 1985). The Birth of the Propaganda State: Soviet Methods of Mass Mobilization, 1917–1929. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 342. ISBN 978-0-521-31398-8.

- Ellul, Jacques (1973). Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes. New York: Vintage Books. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-394-71874-3.

- Tzu, Sun (1977). Samuel B. Griffith (translator) (ed.). The Art of War. Oxford University Press. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-19-501476-1.

- Lasswell, Harold D. (April 15, 1971). Propaganda Technique in World War I. M.I.T. Press. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-262-62018-5.

- Huxley, Aldous (1958). Brave New World Revisited. New York: Harper & Row.

- Andrew, Christopher; Mitrokhin, Vasili (September 20, 2005). The World Was Going Our Way: The KGB and the Battle for the Third World. New York: Basic Books. p. 736. ISBN 978-0-465-00311-2.

- Andrew, Christopher (March 1, 1996). For the President's Eyes Only: Secret Intelligence and the American Presidency from Washington to Bush. New York: HarperPerennial. ISBN 978-0-06-092178-1.

- Riedel, Bruce (March 15, 2010). The Search for Al Qaeda: Its Leadership, Ideology, and Future (2nd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 978-0-8157-0451-5.

- Clark, Charles E. (2000). Uprooting Otherness: The Literacy Campaign in Nep-Era Russia. Susquehanna University Press.

External links