African long-fingered bat

The African long-fingered bat (Miniopterus africanus) is a species of vesper bat in the family Vespertilionidae. It is found only in Kenya. It is found in subtropical or tropical moist montane forests. This species is often considered a synonym of Miniopterus inflatus.[1] The holotype was collected in October 1926 by A. M. Bailey. It was described as a new species in 1936 by Colin Campbell Sanborn.[2]

| African long-fingered bat | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Family: | Miniopteridae |

| Genus: | Miniopterus |

| Species: | M. africanus |

| Binomial name | |

| Miniopterus africanus Sanborn, 1936 | |

Description

It is similar in appearance to the Natal long-fingered bat, but it is much larger. Its dorsal fur is light brown, with the bases of individual hairs darker than their tips. Its ventral fur is lighter than the dorsal fur, with individual hairs brown at the base and gray at the tip. Its forearm is 48.4–50.5 mm (1.91–1.99 in) long. The greatest length of the skull is 16.6–17 mm (0.65–0.67 in) long.[2]

Biology

It is known to be infected with the parasite Polychromophilus melanipherus, which helps support the hypothesis that Haemosporidiasina transitioned from avian hosts to bat hosts in a single evolutionary event. The 2016 study concluded that it was likely that malaria parasites affecting humans and rodents evolved from parasites affecting bats.[3]

The African long-fingered bat's evolutionary lineage diverged from other long-fingered bats approximately 20 million years ago.[4]

In 2013, an individual from this species tested positive for polyomaviruses. However, bats are unlikely to be the source of polyomavirus infection in humans, as none of the lineages found in bats so far is known to infect humans.[5]

Range and habitat

It has only been documented in Kenya.[1] Its type locality is Sanford's Ranch in Mulo, Kenya, which is to the northwest of Addis Ababa. It was collected at 8,000 m (26,000 ft) above sea level.[2] It has been documented roosting in limestone-rich coral caves on the eastern coast of the country.[6]

Conservation

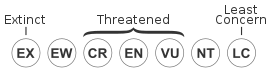

It is currently evaluated as data deficient by the IUCN.[1] Some of the caves that it roosts in are threatened by human activities, such as burning and cutting vegetation growing at the mouths of the caves. Some Kenyans do not understand that bats are important, and may view them as a nuisance or take direct actions to harm them. Caves are also threatened by expanding human population. Kenyans that live near the coastal caves have an overwhelmingly negative view of bats, with 58% of respondents to a questionnaire viewing them as a sign of witchcraft or a bad omen, and 68% thinking that bats are not beneficial in any way. Conversely, this negative perception of the bats may protect them in some way, as one landowner who owned a cave where the African long-fingered bat roosts reported that she did not allow people to enter the cave as she feared it would bring bad omens onto her. This attitude protects the bats in the cave from human disturbance.[6]

References

- Waldien, D.L. & Webala, P. (2020). "Miniopterus africanus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T44859A22073089. Retrieved 10 July 2020.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Sanborn, Colin Campbell. Descriptions and records of African bats. Zoological series. 20. Field Museum of Natural History. pp. 111–112. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- Lutz, H. L.; Patterson, B. D.; Peterhans, J. C. K.; Stanley, W. T.; Webala, P. W.; Gnoske, T. P.; Hackett, S.J.; Stanhope, M. J. (2016). "Diverse sampling of East African haemosporidians reveals chiropteran origin of malaria parasites in primates and rodents". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 99: 7–15. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2016.03.004. PMID 26975691.

- Farkašová, H.; Hron, T.; Pačes, J.; Hulva, P.; Benda, P.; Gifford, R. J.; Elleder, D. (2017). "Discovery of an endogenous Deltaretrovirus in the genome of long-fingered bats (Chiroptera: Miniopteridae)". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (12): 3145–3150. doi:10.1073/pnas.1621224114. PMC 5373376. PMID 28280099.

- Tao, Ying; Shi, Mang; Conrardy, Christina; Kuzmin, Ivan V.; Recuenco, Sergio; Agwanda, Bernard; Alvarez, Danilo A.; Ellison, James A.; Gilbert, Amy T.; Moran, David; Niezgoda, Michael; Lindblade, Kim A.; Holmes, Edward C.; Breiman, Robert F.; Rupprecht, Charles E.; Tong, Suxiang (2013). "Discovery of diverse polyomaviruses in bats and the evolutionary history of the Polyomaviridae". Journal of General Virology. 4 (94): 738–748. doi:10.1099/vir.0.047928-0. PMID 23239573.

- Makori, B. (2015). Survey and Conservation of Cave-Dwelling Bats in Coastal Kenya (PDF) (Report). Karatina, Kenya: Karatina University, School of Natural Resources and Environmental Studies. Retrieved October 9, 2017.