Africa Addio

Africa Addio (also known as Africa: Blood and Guts in the United States and Farewell Africa in the United Kingdom) is a 1966 Italian mondo documentary film co-directed, co-edited and co-written by Gualtiero Jacopetti and Franco Prosperi with music by Riz Ortolani. The film is about the end of the colonial era in Africa. The film was shot over a period of three years by Jacopetti and Prosperi, who had gained fame (along with co-director Paolo Cavara) as the directors of Mondo Cane in 1962. This film ensured the viability of the so-called Mondo film genre, a cycle of "shockumentaries"- documentaries featuring sensational topics, a description which largely characterizes Africa Addio. A tie-in book with the same title, written by John Cohen, was released by Ballantine to coincide with the film's release.[1]

| Africa Addio | |

|---|---|

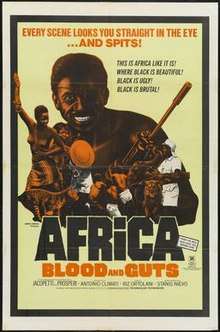

1970 United States theatrical release poster, bearing the title Africa Blood and Guts | |

| Directed by | |

| Produced by | Angelo Rizzoli |

| Written by |

|

| Music by | Riz Ortolani |

| Edited by |

|

| Distributed by | Rizzoli (United States) |

Release date | 1966 |

Running time | 140 minutes |

| Language | Italian |

Historical events depicted

The film includes footage of the Zanzibar revolution, which included the massacre of 1964, which claimed the lives of approximately 5,000 Arabs[2] (estimates range up to 20,000 in the aftermath), as well as of the aftermath of the Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya.

Allegations of staging and inauthenticity

Prior to the film's release, allegations that a scene depicting the execution of a Congolese Simba Rebel had been staged for the camera resulted in co-director Gualtiero Jacopetti's arrest on charges of murder. The film's footage was seized by police, and the editing process was halted during the legal proceedings. He was acquitted after he and co-director Franco Prosperi produced documents proving they had arrived at the scene just before the execution took place.[3][4]

Jacopetti has stated that all images in the film are real and that nothing was ever staged.[5] In the documentary The Godfathers of Mondo, the co-directors stressed that the only scenes they ever staged were in Mondo Cane 2.[3] In the same documentary, Prosperi described their filmmaking philosophy: “Slip in, ask, never pay, never reenact.”[4]

Different versions

The film has appeared in a number of different versions. The Italian and French versions were edited and were provided with narration by Jacopetti himself. The American version, with the explicitly shocking title Africa: Blood and Guts, was edited and translated without the approval of Jacopetti. Indeed, the differences are such that Jacopetti has called this film a betrayal of the original idea.[6] Notable differences are thus present between the Italian and English-language versions in terms of the text of the film. Many advocates of the film feel that it has unfairly maligned the original intentions of the filmmakers. For example, the subtitled translation of the opening crawl in the Italian version reads:

- "The Africa of the great explorers, the huge land of hunting and adventure adored by entire generations of children, has disappeared forever. To that age-old Africa, swept away and destroyed by the tremendous speed of progress, we have said farewell. The devastation, the slaughter, the massacres which we assisted belong to a new Africa– one which if it emerges from its ruins to be more modern, more rational, more functional, more conscious- will be unrecognizable.

- "On the other hand, the world is racing toward better times. The new America rose from the ashes of a few white man, all the redskins, and the bones of millions of buffalo. The new, carved up Africa will rise again upon the tombs of a few white men, millions of black men, and upon the immense graveyards that were once its game reserves. The endeavor is so modern and recent that there is no room to discuss it at the moral level. The purpose of this film is only to bid farewell to the old Africa that is dying and entrust to history the documentation of its agony"[7]

The English version:

- "The old Africa has disappeared. Untouched Jungles, huge herds of game, high adventure, the happy hunting ground- those are the dreams of the past. Today there is a new Africa - modern and ambitious. The old Africa died amidst the massacres and devastations we filmed. But revolutions, even for the better, are seldom pretty. America was built over the bones of thousands of pioneers and revolutionary soldiers, hundreds of thousands of Indians, and millions of Bison. The new Africa emerges over the graves of thousands of whites and Arabs, and millions of blacks, and over the bleak boneyards that once were the game reserves.

- "What the camera sees, it films pitilessly, without sympathy, without taking sides. Judging is for you to do, later. This film only says farewell to the old Africa, and gives to the world the pictures of its agony."[8]

Running length and film credits

Various cuts of the film have appeared over the years. IMDb lists the total runtime as 140 minutes, and a 'complete' version on YouTube runs closest to that at 138 minutes, 35 seconds.[9] This is an Italian language version, with a clear soundtrack and legible English subtitling.

IMDb lists the different runtimes for previously released versions: USA- 122'; Norway- 124'; and Sweden- 116'. An English-language version currently released by Blue Underground runs 128 minutes. The film was released as Africa Blood and Guts in the USA in 1970, at only 83 minutes (over 45 minutes removed in order to focus exclusively on scenes of carnage); according to the text of the box for the Blue Underground release, directors Jacopetti and Prosperi both disowned this version. An R-rated version runs at 80 minutes.

The documentary was written, directed, and edited jointly by Gualtiero Jacopetti and Franco Prosperi and was narrated by Sergio Rossi (not to be confused with the fashion designer of the same name). It was produced by Angelo Rizzoli.

Reception, criticism, and legacy

Reaction to the film was polarized. In Italy, it won the 1966 David di Donatello award for producer Angelo Rizzoli. Some conservative publications, such as Italy's Il Tempo, praised the film.[1] Many commentators, however, accused it of racism and misrepresentation.[10][1] Film directors Octavio Getino and Fernando Solanas harshly criticized the film in their manifesto Toward a Third Cinema, calling Jacopetti a fascist, and asserting that in the film, man is "viewed as a beast," and is "turned into an extra who dies so Jacopetti can comfortably film his execution."[11] Film critic Roger Ebert, in a scathing 1967 review of the shortened American version of the film, called it "racist" and stated that it "slanders a continent." He drew attention to the opening narration:

"Europe has abandoned her baby," the narrator mourns, "just when it needs her the most." Who has taken over, now that the colonialists have left? The advertising spells it out for us: "Raw, wild, brutal, modern-day savages!"[12]

US Ambassador to the United Nations Arthur Goldberg condemned the film as "grossly distorted" and "socially irresponsible," noting the protests of five African UN delegates.[13]

In West Germany, a protest movement against the film emerged after Africa Addio was awarded by the state-controlled movie rating board. The protest was chiefly organized by the Socialist German Student Union (SDS) and groups of African students. In West Berlin, the distributor resigned from showing the film after a series of demonstrations and damage to cinemas.[14]

Jacopetti and Prosperi responded to the criticism by defending their intentions. In the 2003 documentary The Godfathers of Mondo, Prosperi argues that the criticism was due to the fact that, "The public was not ready for this kind of truth," and Jacopetti explicitly states that the film “was not a justification of colonialism, but a condemnation for leaving the continent in a miserable condition.”[4] The subsequent film collaboration between the two men, Addio Zio Tom, explored the horrors of American racial slavery and was intended (in part) to combat the charges of racism leveled against them following the release of Africa Addio[15] (though it too was criticized for perceived racism, particularly by Ebert).[16][1]

In 1968 at the Carnival of Viareggio, a float inspired by the film took part and made by the master of papier-mâché Il Barzella. Some items from this float, along with other memorabilia including a copy of the book by John Cohen, are kept in Museum of Dizionario del Turismo Cinematografico in Verolengo.

Soundtrack

A soundtrack of the music used in the film was later released. The composer was Riz Ortolani (who had scored Mondo Cane that featured the tune later used for the hit single More). When making Africa Addio, lyrics were added to Ortolani's title theme, making a song called "Who Can Say?" that was sung by Jimmy Roselli. The song did not appear in the film, but (unlike the successful song More spawned by Mondo Cane) did appear on the United Artists Records soundtrack album.

Track listing

- "Who Can Say?" (sung by Jimmy Roselli) (02:40)

- "Africa addio" (03:24)

- "I mercenari" (02:17)

- "Il massacro di Maidopei" (04:22)

- "Cape Town" (02:02)

- "Prima del diluvio" (03:18)

- "Le ragazze dell'oceano" (03:55)

- "Verso la libertà" (02:40)

- "Paradiso degli animali" (01:58)

- "Il nono giorno" (04:38)

- "Goodbye Mister Turnball" (02:07)

- "Lo zebrino volante" (02:05)

- "La decimazione" (05:26)

- "Finale Africa addio" (02:15)

References

- Goodall, Mark (October 5, 2017). Sweet & Savage: The World through the Mondo Film Lens. Headpress. ISBN 1909394505.

- Plekhanov, Sergeĭ (2004). A Reformer on the Throne: Sultan Qaboos Bin Said Al Said. Trident Press Ltd. p. 91. ISBN 1-900724-70-7.

- 'A Dog's World: The Mondo Cane Collection, Bill Gibron, December 1, 2003

- Provocateur Gualtiero Jacopetti Dead at 91: Honoring the Man Behind the Mondo Movies Richard Corliss, August 21, 2011

- See the interview with Jacopetti from 1988, reprinted Amok Journal: Sensurround Edition, edited by S. Swezey (Los Angeles: AMOK, 1995), pp. 140-171

- See the interview with Jacopetti, reprinted Amok Journal: Sensurround Edition, edited by S. Swezey (Los Angeles: AMOK, 1995), pp. 140-171.

- Africa Blood and Guts, Gualtiero Jacopetti, et al., 1970

- Africa Addio Archived 2011-02-17 at the Wayback Machine, Gualtiero Jacopetti, et al., 1966

- YouTube, Africa Addio Archived 2016-02-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Goodall, Mark (2006), "Shockumentary evidence: the perverse politics of the Mondo film", in Dennison, Stephanie; Lim, Song Hwee (eds.), Remapping World Cinema: Identity, Culture and Politics in Film, Wallflower Press, p. 121

- Solanas, Fernando; Getino, Octavio (1970–1971). "TOWARD A THIRD CINEMA". Cinéaste. 4 (3): 1–10.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Africa Addio review, Roger Ebert, April 25, 1967

- "GOLDBERG CRITICIZES 'AFRICA ADDIO' FILM". The New York Times. New York City, NY. March 21, 1967. p. 35.

- Niels Seibert: Vergessene Proteste. Internationalismus und Antirassismus 1964–1983. Berlin, 2008.

- The Godfathers of Mondo. Dir. David Gregory. Blue Underground, 2003.

- Farewell Uncle Tom Roger Ebert, 1972

Bibliography

- Stefano Loparco, 'Gualtiero Jacopetti - Graffi sul mondo', Il Foglio Letterario, 2014 - ISBN 9788876064760 (The book contains unpublished documents and the testimonies of Carlo Gregoretti, Franco Prosperi, Riz Ortolani, Katyna Ranieri, Giampaolo Lomi, Pietro Cavara e Gigi Oliviero).