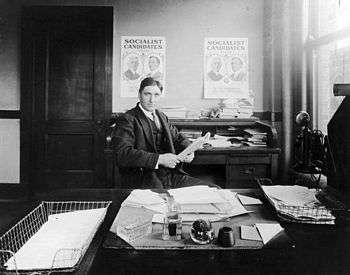

Adolph Germer

Adoph F. Germer (1881–1966) was an American socialist political functionary and union organizer. He is best remembered as National Executive Secretary of the Socialist Party of America from 1916 to 1919. It was during this period that the Left Wing Section of the Socialist Party emerged as an organized faction. Germer was instrumental as one of the leaders of the SPA's "Regular" faction in orchestrating a series of suspensions, expulsions, and "reorganizations" of various Left Wing states, branches, and locals and thereby controlling the pivotal 1919 Emergency National Convention of the SPA, and thus forcing the Left Wing to establish new organizations of their own, the Communist Labor Party of America and the Communist Party of America.

Biography

Early years

Adolph F. Germer was born January 15, 1881, in Welan, East Prussia, Germany the son of a miner.[1] Germer emigrated to the United States with his family in December 1888 and attended public school in Braceville, Illinois. He also attended a Lutheran parochial school and completed his high school coursework via correspondence school.[1] Germer also did course work at LaSalle Extension University.[1]

Germer went to work in the mines like his father at a very early age, first working as a trapper at a coal mine near Staunton, Illinois, at age 11.[1] He was a member of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) from 1894.[1]

Germer escaped a life in the mines by working as a union official. He was elected Secretary of UMWA Local 728 in 1906 and its state legislative committeeman in 1907.[1] That same year he was elected a sub-district vice president of the union.[1] The next year he was elected secretary-treasurer of the sub-district of the UMWA, a position which he retained until 1912.[1] That final year he was also elected representative of the United Mine Workers to the World Miners' Congress in Amsterdam.[1]

Political career

Germer joined the Social Democratic Party of America, forerunner of the Socialist Party of America (SPA) in 1900.[1]

In 1912 Germer was a candidate of the Socialist Party of Illinois for the Illinois legislature.

In 1913, Germer was elected to the governing National Executive Committee of the Socialist Party. At that same time, he worked as an organizer for the UMWA. In December of that year, Germer was arrested while getting off a train at Walsenburg, Colorado, the site of an ongoing mine strike. Germer was held incommunicado in the local jail for nearly a week in solitary confinement and his papers searched. HIs wife, Mabel Germer, was also briefly arrested.[2] Upon his release, Germer continued to work as a UMWA organizer in the bitterly fought Colorado coal strike.

In 1914 Germer was elected Vice President of the Illinois Mine Workers, the state affiliate of the UMWA.[1] He also ran for United States Senate from Illinois as a Socialist in the fall of that year.

From 1916 through 1919, Germer served as National Executive Secretary of the Socialist Party of America, being twice elected by referendum votes of the party membership. His 1916 victory over Carl D. Thompson was made possible by staunch support from the SPA's language federations, many branches of which voted for Germer en bloc, enabling him to defeat the more conservative Thompson.

A staunch antimilitarist and unflinching adherent of the party's anti-World War policies established at its 1917 Emergency National Convention held in St. Louis, Germer was indicted in Chicago by a grand jury under the Espionage Act on Feb. 2, 1918. This secret indictment was made public on March 9 and a trial of Germer and 4 other top members of the Socialist Party began before Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis on Dec. 6, 1918. The trial ended Jan. 4, 1919, and on the 9th day of that same month the jury found Germer and his associates (Victor L. Berger, J. Louis Engdahl, Irwin St. John Tucker, and William F. Kruse) guilty. Landis sentenced each to 20 years in the Federal penitentiary, a sentence which was appealed and later overturned on the basis of judicial bias.

Germer was freed on $25,000 bail pending appeal, a sum put up by a man who was soon to be a political nemesis, the millionaire left wing socialist William Bross Lloyd.

Germer was instrumental in guiding the National Executive Committee in 1919, a group which invalidated the party elections of that year on charges of electoral fraud, and which suspended a number of language federations and reorganized state organizations for purported violations of the SPA's national constitution. It was Germer who organized a caucus of loyal SPA Regulars prior to the opening of the convention on Aug. 30, 1919, and Germer who gaveled that gathering open.

After the bitter 1919 convention, Germer resigned his post as Executive Secretary of the SPA and was replaced by his friend Otto Branstetter. Germer continued to draw a salary from the SPA, working as a National Organizer for the party from October 1919 through 1920.[1] In that year he left the nearly bankrupt national party to work for the relatively more prosperous Local New York as an organizer, a position which he retained through 1922.[1] Germer was also Assistant Secretary of Local New York, working under his friend and ally Julius Gerber from August 1921.

In November 1921, Germer stood as a Socialist candidate for the New York State Assembly in the 16th A.D.

After the 1921 election, Germer moved to Massachusetts, where he served as State Secretary of the Socialist Party of Massachusetts, starting in December.[3] He remained in that position until some time the next year.[3]

Return to union organizing

Thereafter, he left the employment of the Socialist Party, obtaining a job as a worker in the oil industry in California in 1923, where he was a member of the Oil Field, Gas Well and Refinery Workers Union.[1] He later worked as an organizer for that union.[1]

Germer was active in the 1924 Presidential campaign of Robert M. La Follette Sr..

In 1926, Germer returned to Chicago, where he worked for a large real estate firm, remaining in that occupation until the onset of the depression in 1930.[3]

In 1930, Germer was elected a vice president of the reorganized United Mine Workers of America.[3] The following year, he returned to his hometown of Mt. Olive, Illinois and went to work again as a miner until the mine was closed due to the economic downturn.[3]

In June 1931, Germer took a position as editor of the Rockford Labor News, remaining in that role until the end of 1933.[3]

In November 1935, Germer was appointed by John L. Lewis as the first field representative for the Congress of Industrial Organizations. It this capacity, Germer was a participant in the organizing campaigns and strike activities of the auto and rubber workers of the upper Midwest.[3] Germer was particularly important as a key organizer in the 1937 United Auto Workers strike against General Motors.

Germer officially retired from the AFL-CIO on April 1, 1955, but he continued to serve the organization on special assignments.[3]

Death and legacy

After retirement, Germer moved back home to Illinois, dying in Rockford, IL in May 1966.

The main part of Germer's papers are held by the State Historical Society of Wisconsin located at Madison and are available on microfilm. Another smaller assortment, relating to his activity from 1945 to 1947 with the World Federation of Trade Unions, reposes at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York.

An oral history interview was conducted with Germer on his experience as a United Auto Workers organizer in 1959. That material rests at the Reuther Library of Wayne State University, located in Detroit, Michigan.

Footnotes

- Solon DeLeon with Irma C. Hayssen and Grace Poole (eds.), The American Labor Who's Who. New York: Hanford Press, 1925; pg. 84.

- "Germer in Jail," The Party Builder, whole no. 59 (December 20, 1913), pg. 1.

- "Adolph Germer Papers, 1898-1966: Biography/History," Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison.

Works

- "Report to the National Executive Committee," The American Socialist, Special Business Supplement, circa January 1, 1917.

- Organize or Pay! Organizational leaflet no. 1. Chicago: National Office of the Socialist Party, Jan. 1917.

- Report of Executive Secretary [to the] Emergency National Convention, St. Louis, April 7, 1917. St. Louis: n.p., 1917.

- Not Guilty: Charge of Federal Judge Clarence W. Sessions in the Conspiracy Case against Adolph Germer et al. in the District Court of the United States for the Western District of Michigan, Southern Division, Grand Rapids, Michigan, October 9, 1917, to October 18, 1917. Chicago: National Office of the Socialist Party, 1917.

- Defeated? Organizational leaflet no. 13. Chicago: National Office of the Socialist Party, 1918.

- "Report of Executive Secretary to National Executive Committee," August 8, 1918. Published by 1000 Flowers Publishing, Corvallis, OR, 2007.

- In the United States Circuit Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit. October term, A.D. 1918. Victor L. Berger, Adolph Germer, William F. Kruse, Irwin St. John Tucker and J. Louis Engdahl, plaintiffs in error, vs. United States of America, defendant in error. Error to the District Court of the United States for the Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Division, K.M. Landis, Judge ... Brief for the plaintiffs in error. With Messrs. Berger, Kruse, Tucker, and Engdahl. Chicago: The Court, 1919.

- 100 years — For What? Being the Addresses of Victor L. Berger, Adolph Germer, J. Louis Engdahl, William F. Kruse and Irwin St. John Tucker to the Court that Sentenced Them to Serve 100 years in Prison. With Messrs. Berger, Kruse, Tucker, and Engdahl. Chicago: National Office, Socialist Party, n.d. [1919].

- "Letter to Morris Hillquit in Upstate New York from Adolph Germer in Chicago," March 22, 1919. Corvallis, OR: 1000 Flowers Publishing, 2005.

- "A Report to NEC," The Socialist, June 4, 1919. Corvallis, OR: 1000 Flowers Publishing, 2005.

- "National Secretary Germer's Letter of Resignation," New York Call, vol. 12, no. 261 (Sept. 18, 1919).

Further reading

- Randolph Boehm and Martin Paul Schipper, A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of the Adolph Germer Papers. Frederick, MD: University Publications of America, 1987.

- John H.M. Laslett (ed.), "End of an Alliance: Selected Correspondence Between Socialist Party Secretary Adolph Germer, and UMW of A Leaders in World War One," Labor History, vol. 12, no. 4 (Fall 1971), pp. 570–595.

- Lorin Lee Cary, Adolph Germer: From Labor Agitator to Labor Professional. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Wisconsin, 1968.

- Lorin Lee Cary, "Adolph Germer and the 1890s Depression," Illinois State Historical Society Journal, vol. 68 (1975), pp. 337–343. In JSTOR

- Lorin Lee Cary, "Institutionalized Conservatism in the Early CIO: Adolph Germer, a Case Study," Labor History, Vol. 13, no. 4 (Fall 1972), pp. 475–504.

External links

- Works by or about Adolph Germer at Internet Archive

- "Socialist Party of America (1897-1946): Party History," Early American Marxism website. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- "Finding Aid for the Adolph Germer Papers," University of Wisconsin. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- Guide to the Adolph Germer. Papers, 1945-1947. 5256. Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Martin P. Catherwood Library, Cornell University.