Adolf Wamper

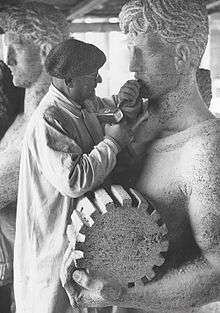

Adolf Wamper (23 June 1901 – 22 May 1977) was a German sculptor. Most of his works were figural, with some in an abstract realist style. During the 1930s he produced monumental sculptures for the Nazi régime; after World War II he taught at the Folkwang University of the Arts.

Early life and education

Adolf Wamper was born in Grevenberg in what is now the town of Würselen, one of five sons raised by their mother, Anna Maria, after their father, Franz Josef Wamper, died in a mining accident in 1907. He was raised Roman Catholic. After finishing school he trained in business and went to work for the Eschweiler Bergwerks-Verein, a leading coal producer. He studied drawing and in 1923 enrolled in the Handwerker- und Kunstgewerbeschule, a school of applied arts in Aachen. He also attended classes for two years at the Aachen Technical University, now RWTH Aachen University. From Aachen he transferred to the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, where he passed his qualifying examinations in 1927 and continued for two further years as an advanced student under Richard Langer.[1][2] He lived in a studio residence in Düsseldorf until 1931. During this time he was already participating in competitions; in 1928 he won the commission to design a monument to be placed in the honorary cemetery for World War I soldiers in Bonn. He exhibited in Cologne in 1930 and at the Reiff Museum in Aachen in 1931. In 1932 he travelled briefly to France and Spain to study art, exhibiting in Paris and Barcelona.[2]

Third Reich

Wamper joined the regional affiliate of the Reichskartell der bildenden Künste, a precursor organisation of the Reichskulturkammer, in 1928; it was superseded by the latter in September 1933 after the Nazis came to power. He joined the Nazi Party on 1 May 1933.[2] He moved to Berlin in 1935, when he was 34, and collaborated with the architect Paul Otto August Baumgarten on the design for the Charlottenburg opera house.[3] He received his first commission for monumental sculpture in 1935, for the two pairs of figures in relief flanking the entrance to the Dietrich-Eckart-Bühne open-air theatre, now the Waldbühne, on the grounds of the 1936 Summer Olympics. On the left, representing Fatherland Celebration, male nudes hold a sword and a spear, a pairing that was to be used more famously by Arno Breker;[4] on the right, representing Artistic Celebration, female nudes hold a laurel wreath and a lyre; the intent was to show the kinship between ancient Greek and Germanic culture.[2][5][6][7][8] Also in 1935, he married Maria Elisabeth Haack, a dentist, and was also involved in the renovation of the Deutsche Oper building, which had become the property of the state and was redesigned to better suit Nazi tastes; he was responsible for the ceiling and for busts of Wagner and Beethoven for the foyer.[2] His work was also part of the sculpture event in the art competition at the 1936 Summer Olympics.[9]

Although he was not in the first rank of officially approved sculptors, such as Breker and Josef Thorak, Wamper continued to receive state commissions until the end of the Nazi period. For example, he created two pairs of figures for the entrance to the Messe Berlin, Agriculture and Handwork and Industry and Commerce (removed in 1978) and reliefs for the Reichsgetreidestelle on Fehrbelliner Platz (destroyed). He also designed a monument in bronze of two warriors for the town of Ahlen, a terracotta relief of Hercules and Hydra for the naval hospital in Stralsund and a statue of Hölderlin for the Hölderlin Society in Tübingen. His Genius of Victory was included in the Great German Art Exhibition of 1940;[2][10] depicting a nude young man with upraised sword, an eagle at his feet,[3] it has been cited as an example of the fascist use of the male body as a symbol of Social Darwinist truth.[11] In 1941 he exhibited The Seasons, a group of four female figures. He was one of 23 sculptors listed in 1940 to work on the reshaping of Berlin under Albert Speer,[2] and in 1944 was placed on the Gottbegnadeten list of artists exempt from military service.[12] He was nonetheless called up in March 1945. (His studio and residence had both been destroyed by bombing and he and his wife had left Berlin for Heepen, now in Bielefeld.) A month later he was captured by U.S. forces and interned at the Golden Mile prisoner-of-war camp at Remagen. While there he used camp mud coated with linseed oil to create the Black Madonna of Remagen, which he gave to the priest in the Kripp section of the town; a facsimile now stands in the Black Madonna Chapel opened in 1987 to commemorate those who died in the camp.[3][13][14]

Post-war

Released in July 1945, Wamper worked with a few students in a small studio in Bielefeld and resumed exhibiting in 1948. Through an acquaintance, Hermann Schardt, who became director there, he was appointed head of the sculpture department at Folkwang University of the Arts in late 1948; he continued to work there until 1970. After the war his work moved away from the monumental, but remained rooted in figurative realism. He created numerous public works, including many for schools, a 1952 relief for the district administration building in Euskirchen, and the Angel of the Flames in front of the town hall in Düren, commemorating the bombing of 16 November 1944. In Essen, his work includes reliefs at the opera house and the entrance to the memorial hall at the Southwest Cemetery;[1] the Market Fountain in the Rüttenscheid section and the monument to the 1963 German Gymnastics Festival are both city landmarks.[2][15][16] He also created the font, altar of the Virgin, and a reredos depicting the Tree of Jesse for the Church of the Birth of the Blessed Virgin (St. Mariä Geburt) in the Frohnhausen section of Essen.[2]

On the occasion of his 65th birthday in 1966, the Folkwang Museum honoured him with an exhibition of sculptures and drawings; on his retirement, the state of North Rhine-Westphalia bestowed the title of professor on him.[2]

He died in Essen in 1977 and was buried with his wife in the Huttrop section; however, the gravesite has been cleared and the reclining sculpture of the couple which marked it has been moved to another location.[2]

- Rüttenscheid Market Fountain

- Monument to 1963 German Gymnastics Festival in Essen

References

- Walther Killy and Rudolf Vierhaus, ed., Dictionary of German Biography Volume 10 Thibaut–Zycha, Munich: Saur, 2006, ISBN 978-3-598-23300-5, p. 343.

- Bettina Oesl, "Adolf Wamper (1901-1977), Bildhauer", Landschaftsverband Rheinland, 6 May 2013, retrieved 16 July 2014 (in German)

- Joe F. Bodenstein, "Adolf Wamper ein Bildhauer der klassischen Schönheit", Prometheus 92, Summer 2004, retrieved 17 July 2014.

- Klaus Wolbert, Die Nackten und die Toten des "Dritten Reiches": Folgen einer politischen Plastik des deutschen Faschismus, Kunstwissenschaftliche Untersuchungen des Ulmer Vereins, Verband für Kunst- und Kulturwissenschaften 12, Gießen: Anabas, 1982, ISBN 9783870380953, p. 212 (in German)

- Antike und Altertumswissenschaft in der Zeit von Faschismus und Nationalsozialismus, University of Zurich colloquium, 14–17 October 1998, ed. Beat Näf with Tim Kammasch, Texts and studies in the history of humanities 1, Mandelbachtal/Cambridge: Edition Cicero, 2001, ISBN 9783934285460, p. 260 (in German)

- Georg Dehio, Handbuch der deutschen Kunstdenkmäler: Berlin, 3rd ed. rev. Sibylle Badstübner-Gröger and Michael Bollé, Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2006, ISBN 9783422031111, p. 229 (in German)

- Photographs, Werner Rittich, Architektur und Bauplastik der Gegenwart, (2nd ed.) Berlin: Rembrandt, 1938, OCLC 490115936 (in German), pp. 56, 58, 59.

- Photographs, Berlin—Reichssportfeld and 1936 Olympics Site: Dietrich-Eckart-Bühne, Third Reich in Ruins, misidentified as by Josef Wackerle.

- "Adolf Wamper". Olympedia. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- Genius of Victory photograph at the exhibit, Haus der Deutschen Kunst, Munich: Part 4—Sculpture, Third Reich in Ruins, retrieved 17 July 2014.

- J. A. Mangan, Shaping the Superman: Fascist Body as Political Icon—Aryan Fascism, Sport in the Global Society, London / Portland, Oregon: Cass, 1999, ISBN 9780714649542, p. 141.

- Ernst Klee, Das Kulturlexikon zum Dritten Reich. Wer war was vor und nach 1945, Frankfurt: Fischer, 2007, ISBN 9783100393265, p. 644 (in German)

- The Black Madonna, Peace Museum Remagen, retrieved 17 July 2014.

- Andrew Rawson, Remagen Bridge: 9th Armoured Infantry Division, Battleground Europe, Crossing the Rhine, Havertown: Pen and Sword, 2004, ISBN 9781783460250, n.p.

- "Rüttenscheider Marktbrunnen", Denkmalliste der Stadt Essen, 24 April 2004 (pdf), archived at the Wayback Machine, 2 October 2013 (in German)

- Denkmal des Deutschen Turnfestes Essen 1963, "Turnfestdenkmal", Denkmalliste der Stadt Essen, 16 September 2004 (pdf), archived at the Wayback Machine, 2 October 2013 (in German)

Further reading

- Wilhelm Westecker. "Adolf Wamper" in Künstler des Ruhrlandes, Essen: Hellweg, 1954. OCLC 81354450. pp. 95–96. (in German)

- Robert Thoms. Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung München 1937–1944. Verzeichnis der Künstler in zwei Bänden Volume II Bildhauer. Berlin: Neuhaus, 2011. ISBN 978-3-937294-02-5.