Adenoid

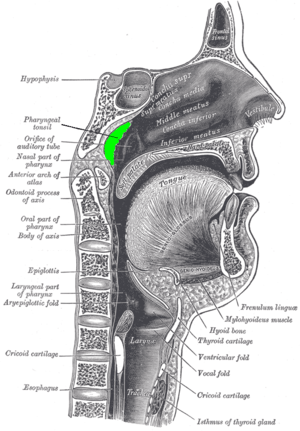

In anatomy, the adenoid, also known as the pharyngeal tonsil or nasopharyngeal tonsil, is the superior-most of the tonsils. It is a mass of lymphatic tissue located behind the nasal cavity, in the roof of the nasopharynx, where the nose blends into the throat. In children, it normally forms a soft mound in the roof and back wall of the nasopharynx, just above and behind the uvula.

| Adenoids | |

|---|---|

Location of the adenoid | |

| Details | |

| System | Lymphatic system |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | tonsilla pharyngea |

| MeSH | D000234 |

| TA | A05.3.01.006 |

| FMA | 54970 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The term adenoid is also used to represent adenoid hypertrophy, the abnormal growth of the pharyngeal tonsils.[1]

Structure

The adenoid is a mass of lymphatic tissue located behind the nasal cavity, in the roof of the nasopharynx, where the nose blends into the throat. The adenoid, unlike the palatine tonsils, has pseudostratified epithelium.[2] The adenoids are part of the so-called Waldeyer ring of lymphoid tissue which also includes the palatine tonsils, the lingual tonsils and the tubal tonsils.

Development

Adenoids develop from a subepithelial infiltration of lymphocytes after the 16th week of embryonic life. After birth, enlargement begins and continues until aged 5 to 7 years.

Microbiome

Species of bacteria such as lactobacilli, anaerobic streptococci, actinomycosis, Fusobacterium species, and Nocardia are normally present by 6 months of age. Normal flora found in the adenoid consists of alpha-hemolytic streptococci and enterococci, Corynebacterium species, coagulase-negative staphylococci, Neisseria species, Haemophilus species, Micrococcus species, and Stomatococcus species.

Clinical significance

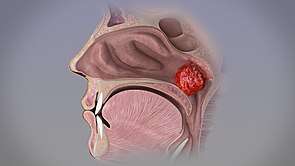

Enlargement

An enlarged adenoid, or adenoid hypertrophy, can become nearly the size of a ping pong ball and completely block airflow through the nasal passages. Even if the enlarged adenoid is not substantial enough to physically block the back of the nose, it can obstruct airflow enough so that breathing through the nose requires an uncomfortable amount of work, and inhalation occurs instead through an open mouth. The enlarged adenoid would also obstruct the nasal airway enough to affect the voice without actually stopping nasal airflow altogether.

Symptomatic enlargement between 18 and 24 months of age is not uncommon, meaning that snoring, nasal airway obstruction and obstructed breathing may occur during sleep. However, this may be reasonably expected to decline when children reach school age, and progressive shrinkage may be expected thereafter.

Adenoid facies

Enlargement of the adenoid, especially in children, causes an atypical appearance of the face, often referred to as adenoid facies.[3] Features of adenoid facies include mouth breathing, an elongated face, prominent incisors, hypoplastic maxilla, short upper lip, elevated nostrils, and a high arched palate.[4]

Removal

Surgical removal of the adenoid is a procedure called adenoidectomy. Adenoid infection may cause symptoms such as excessive mucus production, which can be treated by its removal. Studies have shown that adenoid regrowth occurs in as many as 19% of the cases after removal.[5] Carried out through the mouth under a general anaesthetic (or less commonly a topical), adenoidectomy involves the adenoid being curetted, cauterized, lasered, or otherwise ablated. The adenoid is often removed along with the palatine tonsils.

In popular culture

In 1861 George Catlin published many engravings illustrating adenoid facies and its complications in his book Breath of Life, where he advocated nose-breathing.[6][7]

In his 1984 autobiographical book Boy: Tales of Childhood, author Roald Dahl devotes a chapter to the time he had his adenoids removed without any anaesthetic. This occurred in 1924, when Dahl was 8 years old.

In Gravity's Rainbow, by American novelist Thomas Pynchon, Lord Blatherand Osmo is “assimilated by his own growing Adenoid, some horrible transformation of cell plasma it is quite beyond Edwardian medicine to explain”. Osmo's travail is remotely experienced by Pirate Prentice, a major character.

References

- "Definition of ADENOID". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2018-05-05.

- Histology at KUMC lymphoid-lymph06

- Jefferson, Yosh (2017-02-01). "Mouth breathing: adverse effects on facial growth, health, academics, and behavior". General Dentistry. 58 (1): 18–25, quiz 26–27, 79–80. ISSN 0363-6771. PMID 20129889.

- Wahba, Mohammed. "Adenoid facies". Radiopaedia.org. Radiology Reference Article. Retrieved 2016-11-06.

- Lesinskas, Eugenijus; Drigotas, Martynas (2009-04-01). "The incidence of adenoidal regrowth after adenoidectomy and its effect on persistent nasal symptoms". European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 266 (4): 469–473. doi:10.1007/s00405-008-0892-5. ISSN 1434-4726. PMID 19093130.

- Catlin, George (1864). The breath of life or mal-respiration and its effects upon the enjoyments & life of man.

- Wylie, A (1927). "Rhinology and laryngology in literature and folklore". The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 42 (2): 81–87. doi:10.1017/S0022215100029959.

External links

- "Anatomy diagram: 25420.000-1". Roche Lexicon - illustrated navigator. Elsevier. Archived from the original on 2014-01-01.

- Adenoids: What They Are, How To Recognize Them, What To Do For Them

- Histology at usuhs.mil

- Histology at udel.edu

- /drtbalu otolaryngology online