Acrylamide

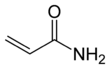

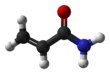

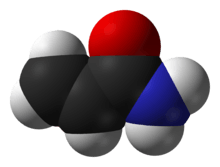

Acrylamide (or acrylic amide) is an organic compound with the chemical formula CH2=CHC(O)NH2. It is a white odorless solid, soluble in water and several organic solvents. It is produced industrially as a precursor to polyacrylamides, which find many uses as water-soluble thickeners and flocculation agents. It is highly toxic, likely to be carcinogenic,[6] and partly for that reason it is mainly handled as an aqueous solution.

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Prop-2-enamide[1] | |||

| Other names

Acrylamide Acrylic amide[2] | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.067 | ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID |

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C3H5NO | |||

| Molar mass | 71.079 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | white crystalline solid, no odor[2] | ||

| Density | 1.322 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | 84.5 °C (184.1 °F; 357.6 K) | ||

| Boiling point | None (polymerization); decomposes at 175-300°C[2] | ||

| 390 g/L (25 °C)[3] | |||

| Hazards | |||

| Main hazards | potential occupational carcinogen[2] | ||

| Safety data sheet | ICSC 0091 | ||

| GHS pictograms |   | ||

GHS hazard statements |

H301, H312, H315, H317, H319, H332, H340, H350, H361, H372[4] | ||

| P201, P280, P301+310, P305+351+338, P308+313[4] | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | 138 °C (280 °F; 411 K) | ||

| 424 °C (795 °F; 697 K) | |||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose) |

100-200 mg/kg (mammal, oral) 107 mg/kg (mouse, oral) 150 mg/kg (rabbit, oral) 150 mg/kg (guinea pig, oral) 124 mg/kg (rat, oral)[5] | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 0.3 mg/m3 [skin][2] | ||

REL (Recommended) |

Ca TWA 0.03 mg/m3 [skin][2] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

60 mg/m3[2] | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

The discovery in 2002 that some cooked foods contain acrylamide attracted significant attention to its possible biological effects.[7] As of 2019, epidemiological studies suggest it is unlikely that dietary acrylamide consumption increases people's risk of developing cancer despite it being a probable carcinogen according to IARC, NTP, and the EPA.[6]

Production

Acrylamide can be prepared by the hydrolysis of acrylonitrile. The reaction is catalyzed by sulfuric acid as well as various metal salts. It is also catalyzed by the enzyme nitrile hydratase.[7] US demand for acrylamide was 253,000,000 pounds (115,000,000 kg) as of 2007, increased from 245,000,000 pounds (111,000,000 kg) in 2006.

-L-asparagine.png)

Acrylamide arises in some cooked foods via a series of steps initiated by the condensation of the amino acid asparagine and glucose. This condensation, one of the Maillard reactions followed by dehydrogenation produces N-(D-glucos-1-yl)-L-asparagine, which upon pyrolysis generates some acrylamide.

Uses

The majority of acrylamide is used to manufacture various polymers, especially polyacrylamide[9][10] used as a thickening agent and in water treatment.[11]

Toxicity and carcinogenicity

U.S. regulation

Acrylamide is classified as an extremely hazardous substance in the United States as defined in Section 302 of the U.S. Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (42 U.S.C. 11002), and is subject to strict reporting requirements by facilities which produce, store, or use it in significant quantities.[12]

Acrylamide is considered a potential occupational carcinogen by U.S. government agencies and classified as a Group 2A carcinogen by the IARC.[13] The Occupational Safety and Health Administration and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health have set dermal occupational exposure limits at 0.03 mg/m3 over an eight-hour workday.[5] In animal models, exposure to acrylamide causes tumors in the adrenal glands, thyroid, lungs, and testes.[2] Acrylamide is easily absorbed by the skin and distributed throughout the organism; the highest levels of acrylamide post-exposure are found in the blood, non-exposed skin, kidneys, liver, testes, and spleen. Acrylamide can be metabolically-activated by cytochrome P450 to a genotoxic metabolite, glycidamide, which is considered to be a critical mode of action to the carcinogenesis of acrylamide. On the other hand, acrylamide and glycidamide can be detoxified via conjugation with glutathione to form acrylamide- and isomeric glycidamide-glutathione conjugates,[14] subsequently metabolized to mercapturic acids and excreted in urine. Acrylamide has also been found to have neurotoxic effects in humans who have been exposed. Animal studies show neurotoxic effects as well as mutations in sperm.[13]

Hazards

Acrylamide is also a skin irritant and may be a tumor initiator in the skin, potentially increasing risk for skin cancer. Symptoms of acrylamide exposure include dermatitis in the exposed area, and peripheral neuropathy.[13]

Laboratory research has found that some phytochemicals may have the potential to be developed into drugs which could alleviate the toxicity of acrylamide.[15]

Occurrence in food and associated health risks

Discovery of acrylamide in foods

Acrylamide was discovered in foods in April 2002 by Eritrean scientist Eden Tareke in Sweden; she found the chemical in starchy foods such as potato chips (potato crisps), French fries (chips), and bread that had been heated higher than 120 °C (248 °F). Production of acrylamide in the heating process was shown to be temperature-dependent. It was not found in food that had been boiled,[16] or in foods that were not heated.[17]

Acrylamide has been found in roasted barley tea, called mugicha in Japanese. The barley is roasted so it is dark brown prior to being steeped in hot water. The roasting process produced 200–600 micrograms/kg of acrylamide in mugicha.[18] This is less than the >1000 micrograms/kg found in potato crisps and other fried whole potato snack foods cited in the same study and it is unclear how much of this is ingested after the drink is prepared. Rice cracker and sweet potato levels were lower than in potatoes. Potatoes cooked whole were found to have significantly lower acrylamide levels than the others, suggesting a link between food preparation method and acrylamide levels.

Acrylamide levels appear to rise as food is heated for longer periods of time. Although researchers are still unsure of the precise mechanisms by which acrylamide forms in foods,[19] many believe it is a byproduct of the Maillard reaction. In fried or baked goods, acrylamide may be produced by the reaction between asparagine and reducing sugars (fructose, glucose, etc.) or reactive carbonyls at temperatures above 120 °C (248 °F).[20][21]

Later studies have found acrylamide in black olives,[22] dried plums,[23][24] dried pears,[23] coffee,[25][26] and peanuts.[24]

The US FDA has analyzed a variety of U.S. food products for levels of acrylamide since 2002.[27]

According to the EFSA, the main toxicity risks of acrylamide are "Neurotoxicity, adverse effects on male reproduction, developmental toxicity and carcinogenicity".[28][29] However, according to their research, there is no concern on non-neoplastic effects. Furthermore, while the relation between consumption of acrylamide and cancer in rats and mice has been shown, it is still unclear whether acrylamide consumption has an effect on the risk of developing cancer in humans, and existing epidemiological studies in humans are very limited and do not show any relation between acrylamide and cancer in humans.[28][30] Food industry workers exposed to twice the average level of acrylamide do not exhibit higher cancer rates.[28]

Acceptable limits

Although acrylamide has known toxic effects on the nervous system and on fertility, a June 2002 report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the World Health Organization attempting to establish basic toxicology (threshold limit value, no-observed-adverse-effect levels, tolerable daily intake, etc.) concluded the intake level required to observe neuropathy (0.5 mg/kg body weight/day) was 500 times higher than the average dietary intake of acrylamide (1 μg/kg body weight/day). For effects on fertility, the level is 2,000 times higher than the average intake.[31] From this, they concluded acrylamide levels in food were safe in terms of neuropathy, but raised concerns over human carcinogenicity based on known carcinogenicity in laboratory animals.[31]

Opinions of health organizations

The American Cancer Society say that laboratory studies have shown that acrylamide is likely to be a carcinogen, but that as of 2019 evidence from epidemiological studies suggest that dietary acrylamide is unlikely to raise the risk of people developing cancer.[6]

The World Health Organization (WHO) has set up a clearinghouse for information about acrylamide that includes a database of researchers and data providers; references for research published elsewhere; information updates about the current status of research efforts; and updates on information relevant to the health risk of acrylamide in food.[32]

HEATOX (heat-generated food toxicants) study in Europe

The Heat-generated Food Toxicants (HEATOX) Project was a European Commission-funded multidisciplinary research project running from late 2003 to early 2007. Its objectives were to "estimate health risks that may be associated with hazardous compounds in heat-treated food, [and to] find cooking/processing methods that minimize the amounts of these compounds, thereby providing safe, nutritious, and high-quality food-stuffs."[33][34] It found that "the evidence of acrylamide posing a cancer risk for humans has been strengthened,"[35] and that "compared with many regulated food carcinogens, the exposure to acrylamide poses a higher estimated risk to European consumers."[33] HEATOX sought also to provide consumers with advice on how to lower their intake of acrylamide, specifically pointing out that home-cooked food tends to contribute far less to overall acrylamide levels than food that was industrially prepared, and that avoiding overcooking is one of the best ways to minimize exposure at home.[33]

Public awareness

On April 24, 2002, the Swedish National Food Administration announced that acrylamide can be found in baked and fried starchy foods, such as potato chips, breads, and cookies. Concern was raised mainly because of the probable carcinogenic effects of acrylamide. This was followed by a strong, but short-lived, interest from the press.

On August 26, 2005, California attorney general Bill Lockyer filed a lawsuit against four makers of french fries and potato chips – H.J. Heinz Co., Frito-Lay, Kettle Foods Inc., and Lance Inc. – to reduce the risk to consumers from consuming acrylamide.[36] The lawsuit was settled on August 1, 2008, with the food producers agreeing to cut acrylamide levels to 275 parts per billion in three years, to avoid a Proposition 65 warning label.[37] The companies avoided trial by agreeing to pay a combined $3 million in fines as a settlement with the California attorney general's office.[38]

In 2016, the UK Food Standards Agency launched a campaign called "Go for Gold", warning of the possible cancer risk associated with cooking potatoes and other starchy foods at high temperatures.[28][39]

In 2018, a judge in California ruled that the coffee industry had not provided sufficient evidence that acrylamide contents in coffee were at safe enough levels to not require a Proposition 65 warning.[40]

Occurrence in cigarettes

Cigarette smoking is a major acrylamide source.[41][42] It has been shown in one study to cause an increase in blood acrylamide levels three-fold greater than any dietary factor.[43]

See also

- Acrydite: research on this compound casts light on acrylamide

- Acrolein

- Deep-frying

- Deep fryer

- Vacuum fryer

- Substance of very high concern

- Heterocyclic amines

- Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

References

- "Front Matter". Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. p. 842. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-FP001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0012". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- "Human Metabolome Database: Showing metabocard for Acrylamide (HMDB0004296)".

- Sigma-Aldrich Co., Acrylamide. Retrieved on 2013-07-20.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1994). "Documentation for Immediately Dangerous To Life or Health Concentrations (IDLHs) - Acrylamide".

- "Acrylamide and Cancer Risk". American Cancer Society. 11 February 2019.

- Ohara, Takashi; Sato, Takahisa; Shimizu, Noboru; Prescher, Günter; Schwind, Helmut; Weiberg, Otto; Marten, Klaus; Greim, Helmut (2003). "Acrylic Acid and Derivatives". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a01_161.pub2.

- Mendel Friedman (2003). "Chemistry, Biochemistry, and Safety of Acrylamide. A Review". J. Agric. Food Chem. 51 (16): 4504–4526. doi:10.1021/jf030204+. PMID 14705871.

- Environment Canada; Health Canada (August 2009). "Screening Assessment for the Challenge: 2-Propenamide (Acrylamide)". Environment and Climate Change Canada. Government of Canada.

- Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics (September 1994). "II. Production, Use, and Trends" (plain text). Chemical Summary for Acrylamide (Report). United States Environmental Protection Agency. EPA 749-F-94-005a. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- "Polyacrylamide". Hazardous Substances Data Bank. United States National Library of Medicine. February 14, 2003. Consumption Patterns. CASRN: 9003-05-8. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- "40 C.F.R.: Appendix A to Part 355—The List of Extremely Hazardous Substances and Their Threshold Planning Quantities" (PDF) (July 1, 2008 ed.). Government Printing Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2012. Retrieved October 29, 2011. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Dotson, GS (April 2011). "NIOSH skin notation (SK) profile: acrylamide [CAS No. 79-06-1]" (PDF). DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2011-139.

- Luo, Yu-Syuan; Long, Tai-Ying; Shen, Li-Ching; Huang, Shou-Ling; Chiang, Su-Yin; Wu, Kuen-Yuh (July 2015). "Synthesis, characterization and analysis of the acrylamide-and glycidamide-glutathione conjugates". Chemico-Biological Interactions. 237: 38–46. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2015.05.002. PMID 25980586.

- Adewale OO, Brimson JM, Odunola OA, Gbadegesin MA, Owumi SE, Isidoro C, Tencomnao T (2015). "The Potential for Plant Derivatives against Acrylamide Neurotoxicity". Phytother Res (Review). 29 (7): 978–85. doi:10.1002/ptr.5353. PMID 25886076.

- "Acrylamide: your questions answered". Food Standards Agency. 3 July 2009. Archived from the original on 2012-02-12.

- Tareke E; Rydberg P; et al. (2002). "Analysis of acrylamide, a carcinogen formed in heated foodstuffs". J. Agric. Food Chem. 50 (17): 4998–5006. doi:10.1021/jf020302f. PMID 12166997.

- Ono, H; Chuda, Y; Ohnishi-Kameyama, M; Yada, H; Ishizaka, M; Kobayashi, H; Yoshida, M (2003). "Analysis of acrylamide by LC-MS/MS and GC-MS in processed Japanese foods". Food Additives and Contaminants. 20 (3): 215–20. doi:10.1080/0265203021000060887. PMID 12623644.

- Jung, MY; Choi, DS; Ju, JW (2003). "A Novel Technique for Limitation of Acrylamide Formation in Fried and Baked Corn Chips and in French Fries". Journal of Food Science. 68 (4): 1287–1290. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.2003.tb09641.x.

- Mottram DS; Wedzicha BL.; Dodson AT. (2002). "Acrylamide is formed in the Maillard reaction". Nature. 419 (6906): 448–449. doi:10.1038/419448a. PMID 12368844.

- Van Noorden, Richard (5 December 2007). "Acrylamide cancer link confirmed". Chemistry World.

- "Acrylamide detected in prune juice and olives" Food Safety & Quality Control Newsletter 26 March 2004, William Reed Business Media SAS, citing "Survey Data on Acrylamide in Food: Total Diet Study Results" Archived 2009-06-05 at the Wayback Machine United States Food and Drug Administration February 2004; later updated in June 2005, July 2006, and October 2006

- Cosby, Renata (September 20, 2007). "Acrylamide in dried Fruits". ETH Life. Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich. Retrieved 2017-05-29.

- De Paola, Eleonora L; Montevecchi, Giuseppe; Masino, Francesca; Garbini, Davide; Barbanera, Martino; Antonelli, Andrea (February 2017). "Determination of acrylamide in dried fruits and edible seeds using QuEChERS extraction and LC separation with MS detection". Food Chemistry. 217: 191–195. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.08.101. PMID 27664625.

- Mucci, LA; Sandin, S; Bälter, K; Adami, HO; Magnusson, C; Weiderpass, E (2005). "Acrylamide intake and breast cancer risk in Swedish women". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 293 (11): 1326–7. doi:10.1001/jama.293.11.1326. PMID 15769965. S2CID 46166341.

- Top Eight Foods by Acrylamide Per Portion Archived 2016-03-02 at the Wayback Machine. p. 17. jifsan.umd.edu (2004). Retrieved on 2012-06-11.

- Survey Data on Acrylamide in Food: Individual Food Products. Fda.gov. Retrieved on 2012-06-11.

- "Food Controversies—Acrylamide". Cancer Research UK. August 19, 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- "Scientific Opinion on acrylamide in food". EFSA Journal. 13 (6): 4104. June 4, 2015. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4104.

- "Acrylamide and Cancer Risk". National Cancer Institute (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). December 5, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- FAO/WHO Consultation on the Health Implications of Acrylamide in Food; Geneva, 25–27 June 2002, Summary Report. (PDF) . Retrieved on 2014-11-09.

- "Acrylamide". WHO. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017.

- Heat-generated Food Toxicants; Identification, Characterisation and Risk Minimisation. (PDF) . Retrieved on 2012-06-11.

- HEATOX, Heat-generated food toxicants: identification, characterisation and risk minimisation. (PDF) . Retrieved on 2012-06-11.

- HEATOX project completed – brings new pieces to the Acrylamide Puzzle. (PDF) . Retrieved on 2012-06-11.

- Attorney General Lockyer Files Lawsuit to Require Consumer Warnings About Cancer-Causing Chemical in Potato Chips and French Fries Archived 2010-02-28 at the Wayback Machine, Office of the attorney general, State of California, Department of justice

- Egelko, Bob (2 August 2008). "Lawsuit over potato chip ingredients settled". SFGate.

- "Settlement will reduce carcinogens in potato chips". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2008-08-21. Retrieved 2008-08-02.

- "Families urged to 'Go for Gold' to reduce acrylamide consumption". Food Standards Agency. January 23, 2017. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- Raymond, Nate (29 March 2018). "Starbucks coffee in California must have cancer warning, judge says". Reuters. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- "Public Health Statement for Acrylamide". ATSDR. CDC. December 2012.

- Vesper, HW; Bernert, JT; Ospina, M; Meyers, T; Ingham, L; Smith, A; Myers, GL (2007). "Assessment of the Relation between Biomarkers for Smoking and Biomarkers for Acrylamide Exposure in Humans". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 16 (11): 2471–2478. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-1058. PMID 18006939.

- Olesen, PT; Olsen, A; Frandsen, H; Frederiksen, K; Overvad, K; Tjønneland, A (2008). "Acrylamide exposure and incidence of breast cancer among postmenopausal women in the Danish Diet, Cancer and Health Study". International Journal of Cancer. 122 (9): 2094–100. doi:10.1002/ijc.23359. PMID 18183576. S2CID 22388855.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Acrylamide. |