Acorn woodpecker

The acorn woodpecker (Melanerpes formicivorus) is a medium-sized woodpecker, 21 cm (8.3 in) long, with an average weight of 85 g (3.0 oz).

| Acorn woodpecker | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male in California, United States | |

| |

| Female in Arizona, United States | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Piciformes |

| Family: | Picidae |

| Genus: | Melanerpes |

| Species: | M. formicivorus |

| Binomial name | |

| Melanerpes formicivorus (Swainson, 1827) | |

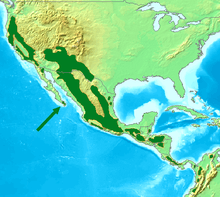

| |

| Range of M. formicivorus | |

.jpg)

Description

The adult acorn woodpecker has a brownish-black head, back, wings and tail, white forehead, throat, belly and rump. The eyes are white. There is a small part on the small of their backs where there are some green feathers. The adult male has a red cap starting at the forehead, whereas females have a black area between the forehead and the cap. The white neck, throat, and forehead patches are distinctive identifiers. When flying, they take a few flaps of their wings and drop a foot or so. White circles on their wings are visible when in flight. Acorn woodpeckers have a call that sounds almost like they are laughing.

Breeding

Habitat

The acorn woodpecker's habitat is forested areas with oaks in the coastal areas and foothills of Oregon, California, and the southwestern United States, south through Central America to Colombia.[2] This species may occur at low elevations in the north of its range, but rarely below 1,000 m (3,300 ft) in Central America, and it breeds up to the timberline. Nests are excavated in a large cavity in a dead tree or a dead part of a tree.

Pairs and communities

Field studies have shown that breeding groups range from monogamous pairs to breeding collectives, sometimes called "coalitions". Cooperative breeding, defined as more than two birds taking care of nestlings in the nest, is a relatively rare evolutionary trait that is thought to occur in only nine percent of bird species.[3] With the acorn woodpecker, cooperative breeding occurs in two ways: coalitions and family groups. Coalitions of adult acorn woodpeckers nest together, localizing to storage granaries.[4] Additionally, adult offspring often stay in their parents' nest and help raise the next generation of woodpeckers.[5] It is generally believed that limited territories drive cooperative breeding behavior in birds, and in the case of the acorn woodpecker, this limited territory is the acorn storage granary.[5]

Breeding coalitions consist of up to seven co-breeding males and up to three joint-nesting females. However, most nests are made up of only three males and two females.[4] Nesting groups can also contain up to ten offspring helpers.[6] These breeding coalitions are typically closely related. The males are often brothers, and the females are usually sisters. Inbreeding is rare, however, meaning that co-breeders of the opposite sex are almost never related.[7]

In groups with more than one breeding female, the females put their eggs into a single nest cavity. A female usually destroys any eggs in the nest before she starts to lay. Once all the females start to lay, they stop removing eggs.[8] Young from a single brood have been found with multiple paternity.[9]

Diet and food storage

Diet

Acorn woodpeckers, as their name implies, depend heavily on acorns for food. Acorns are such an important resource to the California populations that acorn woodpeckers may nest in the fall to take advantage of the fall acorn crop, a rare behavior in birds.[10]

Acorn woodpeckers also feed on insects, sap, and fruit. They can be seen sallying from tree limbs to catch insects, eating fruit and seeds, and drilling holes to drink sap.

Storing acorns

In some parts of their range, such as California, the woodpeckers create granaries or "acorn trees" by drilling holes in dead trees, dead branches, telephone poles, and wooden buildings. They also drill holes in the thick bark of mature living trees, notably the Ponderosa Pine in California. These holes, always above the snow line so that the acorns can be retrieved in winter, can be observed in the hundreds on large trees. They do not harm the tree.

The woodpeckers then collect acorns and find a hole that is just the right size for the acorn. As acorns dry out, they are moved to smaller holes and granary maintenance requires a significant amount of the bird's time. The acorns are visible, and a group defends its granary against potential cache robbers like Steller's jays and western scrub jays.

In parts of its range the acorn woodpecker does not construct a "granary tree", but instead stores acorns in natural holes and cracks in bark. If the stores are eaten, the woodpecker will move to another area, even going from Arizona to Mexico to spend the winter.

Threats and degradation

.jpg)

Acorn woodpeckers, like many other species, are threatened by habitat loss and degradation. Competition for nest cavities by non-native species is an ongoing threat in urbanized areas. Conservation of this species is dependent on the maintenance of functional ecosystems that provide the full range of resources upon which the species depends. These include mature forests with oaks capable of producing large mast crops and places for the woodpeckers to nest, roost, and store mast. Residents are encouraged to preserve mature oak and pine-oak stands of trees and to provide dead limbs and snags for nesting, roosting, and granary sites to help preserve the acorn woodpecker's population.

Popular culture

Walter Lantz is believed to have patterned the call of his cartoon character Woody Woodpecker on that of the acorn woodpecker, while patterning his appearance on that of the pileated woodpecker, which has a prominent crest.[11]

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Melanerpes formicivorus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scofield, D., Alfaro, V., Sork, V., Grivet, D., Martinez, E., Papp, J., Pluess, A., Koenig, W., and Smouse, E. (2010). Foraging patterns of acorn woodpeckers (Melanerpes formicivorus) on valley oak (Quercus lobata Nee) in two California oak savanna-woodlands. Oecologia 166:187–196.

- Cockburn, A. (2006). Prevalence of different modes of parental care in birds. Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences 273:1375-1383.

- Koenig, W.D. (1981). Reproductive success, group size, and the evolution of cooperative breeding in the acorn woodpecker. American Naturalist 22:505–523.

- Hatchwell, B.J., and J. Komdeur. (2000). Ecological constraints, life history traits and the evolution of cooperative breeding. Animal Behaviour 59:1079-1086.

- Haydock, J., and W.D Koenig. (2002). Reproductive skew in the polygynandrous Acorn Woodpecker. American Naturalist 162:277–289.

- Koenig, W.D., Haydock, J., and M. Stanbeck. (1998). Reproductive roles in the cooperatively breeding Acorn Woodpecker: incest avoidance versus reproductive competition Archived 25 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine. American Naturalist 151:243–255.

- Koenig, W.D., Mumme, R.L., Stanback, M., and F.A. Pitelka. (1995). Patterns and consequences of egg destruction among joint-nesting acorn woodpeckers. Animal Behaviour 50:607–621.

- Joste, N., Ligon, D., and Stacey, P. (1985). Shared paternity in the Acorn Woodpecker. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 17(1):39-41.

- Koenig, W.D., and Stahl, J.T. (2007). Condor 109(2):334-350.

- "Woody The Acorn (Not Pileated) Woodpecker". NPR. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

Further reading

- Haydock J., Koenig W. D., & Stanback, M. T. (2001). Shared parentage and incest avoidance in the cooperatively breeding acorn woodpecker. Molecular Ecology, 10, 1515–1525.

- Stiles, F Gary; Skutch, Alexander Frank (1989), A guide to the birds of Costa Rica, Ithaca, New York: Comstock, ISBN 978-0-8014-2287-4

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to the acorn woodpecker. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Melanerpes formicivorus |

- Acorn woodpecker Species Account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Acorn woodpecker (Archived 2009-10-24), a bibliographic resource

- Acorn woodpecker - Melanerpes formicivorus - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- "Acorn woodpecker media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Stamps (for El Salvador, Mexico) with Range Map at bird-stamps.org

- Acorn woodpecker photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Acorn woodpecker at the US Fish & Wildlife Service Digital Repository