Acmella oleracea

Acmella oleracea is a species of flowering herb in the family Asteraceae. Common names include toothache plant, paracress, Sichuan buttons, buzz buttons,[2] tingflowers and electric daisy.[3] Its native distribution is unclear, but it is likely derived from a Brazilian Acmella species.[4] It is grown as an ornamental and attracts fireflies when in bloom. It is used as a medicinal remedy in various parts of the world. A small, erect plant, it grows quickly and bears gold and red inflorescences. It is frost-sensitive but perennial in warmer climates.

| Acmella oleracea | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | A. oleracea |

| Binomial name | |

| Acmella oleracea (L.) R.K.Jansen | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Its specific epithet oleracea means "vegetable/herbal" in Latin and is a form of holeraceus (oleraceus).[5][6]

Culinary uses

For culinary purposes, small amounts of shredded fresh leaves are said to add a unique flavour to salads. Cooked leaves lose their strong flavour and may be used as leafy greens. Both fresh and cooked leaves are used in dishes such as stews in northern Brazil, especially in the state of Pará. They are combined with chilis and garlic to add flavor and vitamins to other foods.[7]

The flower bud has a grassy taste followed by a strong tingling or numbing sensation and often excessive salivation, with a cooling sensation in the throat.[7] The buds are known as "buzz buttons", "Sichuan buttons", "sansho buttons", and "electric buttons".[8] In India, they are used as flavoring in chewing tobacco.[8]

A concentrated extract of the plant, sometimes called jambu oil or jambu extract, is used as a flavoring agent in foods, chewing gum, and chewing tobacco.[9][10][11][12] The oil is traditionally extracted from all part of the plant.[9] EFSA and JECFA reviewed a feeding study in rats conducted by Moore et al. and both authorities recognized that the no adverse effect level for spilanthol was 572 mg/kg b.w./day, yielding a safe dose of spilanthol of 1.9 mg/kg b.w./day, or 133.5 mg/70-kg-male/day, 111 mg/58-kg-female/day, or 38 mg/20-kg-child/day.[11][12]

Jambu extract as a flavoring agent is described as having a citrus, herbal, tropical or musty odor, and its taste can be described as pungent, cooling, tingling, numbing, or effervescent. Thus, as described,[13] the flavor use of jambu extract includes the ability induce a mouth-watering sensation and the ability to promote the production of saliva. Spilanthol, the major constituent of jambu extract,[14] is responsible for the perception of a mouth-watering flavor sensation, as well as the ability to promote salivation as a sialogogue, perhaps through its astringent action or its pungent taste.[15][16]

Jambu extract can also be used in cosmetics and shampoos.[17]

Cultivation

This plant prefers well-drained, black (high organic content) soil. If starting outdoors, the seeds should not be exposed to cold weather, so start after last frost. Seeds need direct sunlight to germinate, so should not be buried.[18]

Medicinal uses

A decoction or infusion of the leaves and flowers is a traditional remedy for stammering, toothache, and stomatitis.[7]

An extract of the plant has been tested against various yeasts and bacteria and was essentially inactive.[19] It has been shown to have a strong diuretic action in rats.[20]

As a bush plant used for treating toothache, the analgesic effect of the Spilanthes plant has been attributed to the presence of constituents containing an N-isobutylamide moiety, such as spilanthol, a substance that has been found to be an effective sialogogue, an agent that promotes salivation.[21] Spilanthol is absorbed trans-dermally and through the buccal mucosa.[22][23] Spilanthol may activate TRPA1, a specific transient receptor potential (TRP) ion channel in the oral cavity.[24] In addition to capsaicin, allyl isothiocyanate, and cinnamaldehyde,[25] spilanthol is also reported to affect the catecholamine nerve pathways present in the oral cavity that promote the production of saliva,[14] which is responsible for its ability to induce a mouth-watering sensation when used as a flavor (and associated with the tingling or pungent flavoring sensation in some individuals).

Since 2000, there are several medicinal activities reported for Acmella oleracea:[14][26]

| Pharmacological activity | Species | Part used | Type of extract | Models used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimalarial, larvicidal | S. acmella Murr. | Flowers | Ethanol | Anopheles, Aedes, Culex larvae |

| Antinociception, antihyperalgesic | S. acmella | Flowers | CWE | Formalin test of nociception and carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia in rats |

| Antinociception, antihyperalgesic | Acmella uliginosa, (Sw.) Cass | Flowers | Methanol | Chemicals (acetic acid-induced abdominal constriction and formalin-, capsaicin-, glutamate-induced paw-licking test) and thermal models (hot-plate test) of nociception in mice |

| Immunomodulatory | S. acmella Murr. | Leaves | Ethanol | Macrophage function in mice |

| Immunomodulatory | S. acmella | Leaves | Ethanol | Neutrophil adhesion test in rat |

| Antiviral | S. americana | Flowers | NA | NA |

| Insecticidal | S. calva | Leaves and flowers | Petroleum ether, ethyl acetate and methanol | Helopeltis theivora |

| Antimalarial, larvicidal | S. acmella, S. calva, S. paniculata | Flowers | Hexane | A. stephensi, A. culicifacies, C. quinquefasciatus larvae |

| Antioxidant | S. acmella | Leaves, stems | Methanol | DPPH, SOD assay |

| Antihepatoxic | S. ciliata | Whole plant | Ethanol | Paracetamol-induced hepatic damage in rats |

| Antimicrobial | S. calva | Roots | Methanol | Oral microflora: Streptococcus mutans, Lactobacillus acidophilus and Candida albicans |

| Anti-inflammatory | S. acmella | Aerial parts | Ethanol | Lipopolysaccharide-activated murine macrophage model |

| Antimalarial, larvicidal | S. mauritiana | Aerial parts | Methanol extract | Aedes aegypti larvae |

| Insecticidal | S. acmella Murr. | Leaves and flowers | Aqueous | Chilo partellus |

| Diuretic | S. acmella | Flowers | CWE | Hydrated rats |

| Antioxidant | S. acmella Murr. | Aerial parts | Chloroform, hexane, ethyl actate, methanol | 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) assay |

| Antimicrobial | S. americana | Whole plant | Aqueous, ethanol and hexane | Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus hemolytic, Bacillus cereus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli |

| Antipyretic | S. acmella Murr. | NA | Aqueous | Aspirin-treated rats |

| Diuretic | S. acmella | Leaves | Petroleum ether, chloroform and ethanol | Hydrated Wistar albino rats |

| Antimicrobial | S. paniculata | Leaves | NA | Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Candida

albicans and Microsporum gypseum |

| Antimicrobial | S. mauritiana | Roots and flowers | NA | Staphylococcus, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, Escherichia and Klebsiella, Salmonella |

| Antimicrobial | S. mauritiana | Roots and flowers | NA | Candida species and Aspergillus species |

| Antimicrobial | S. acmella Linn. | Flower heads | Petroleum ether | Fusarium oxysporium, F. moniliformis, Aspergillus Niger and A. paraciticus |

| Local anaesthetic | S. acmella Murr. | NA | Aqueous | Xylocaine-induced guinea pig and frog |

| Antimalarial, larvicidal | S. mauritiana | Leaves | Crude powder | A. gambiae, Culex larvae |

| Anti-inflammatory | S. acmella | Aerial parts | Aqueous | Carragenan-induced paw edema in rats |

| Aphrodisiac | S. acmella L. Murr. | Flowers | Ethanol | Nitric oxide release in human corpus cavernosum cell line and penile erection in rats |

| Insecticidal | S. acmella | NA | NA | Periplaneta Americana |

| HIV-1 protease inhibitor | S. acmella L. | Whole plant | Chloroform, methanol and water | In vitro HIV-1 protease solution assay method |

| Analgesic | S. acmella | Aerial parts | Aqueous | Acetic acid-induced writhing response in albino mice |

| Pancreatic lipase-inhibitory | S. acmella | Flowers | Ethanol | In vitro test |

| Vasorelaxant | S. acmella Murr. | Aerial parts | Chloroform, hexane, ethyl acetate, methanol | Phenethylephrine-induced rat |

| Antimutagenic | S. calva | NA | Chloroform | Ames Salmonella/microsome assay |

| Convulsant | S. acmella | Whole plant | Hexane | Electroencephalograph response of rats |

Active chemicals

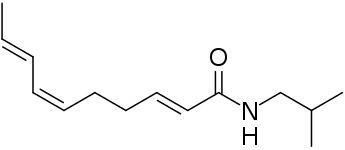

Spilanthol: (2E,6Z,8E)-deca-2,6,8-trienoic acid isobutyl amide

Spilanthol: (2E,6Z,8E)-deca-2,6,8-trienoic acid isobutyl amide (2E,7Z,9E)-Undeca-2,7,9-trienoic acid isobutyl amide, another alkylamide from Acmella oleracea

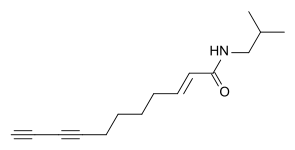

(2E,7Z,9E)-Undeca-2,7,9-trienoic acid isobutyl amide, another alkylamide from Acmella oleracea (2E)-Undeca-2-en-8,10-diynoic acid isobutyl amide

(2E)-Undeca-2-en-8,10-diynoic acid isobutyl amide

The most important taste-active molecules present are fatty acid amides such as spilanthol, which is responsible for the trigeminal and saliva-inducing effects of the plant.[27] It also contains stigmasteryl-3-O-b-D-glucopyranoside and a number of triterpenes. The isolation and total synthesis of the active ingredients have been reported.[28]

Biological pest control

Extracts were bioassayed against yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti) and corn earworm moth (Helicoverpa zea) larvae. The spilanthol proved effective at killing mosquitoes, with a 24-hour LD100 of 12.5 µg/mL, and 50% mortality at 6.25 µg/mL. The mixture of spilanthol isomers produced a 66% weight reduction of corn earworm larvae at 250 µg/mL after 6 days.[27]

See also

References

- Flann, C (ed) 2009+ Global Compositae Checklist

- Bradt, Hilary; Austin, Daniel (2017). Madagascar. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 106. ISBN 9781784770488.

- Wong, James (September 2012). James Wong's Homegrown Revolution. W&N. p. 197. ISBN 978-0297867128.

- Acmella oleracea. Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine PROTA.

- Parker, Peter (2018). A Little Book of Latin for Gardeners. Little Brown Book Group. p. 328. ISBN 978-1-4087-0615-2.

oleraceus, holeraceus = relating to vegetables or kitchen garden

- Whitney, William Dwight (1899). The Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia. Century Co. p. 2856.

L. holeraceus, prop. oleraceus, herb-like, holus, prop. olus (oler-), herbs, vegetables

- Benwick, B. S. Like a Taste That Tingles? Then This Bud's for You. Washington Post. October 3, 2007.

- It's Shocking, But You Eat It. All Things Considered. NPR. February 28, 2009.

- Burdock, George A. (2005). Fenaroli's Handbook of Flavor Ingredients (5th ed.). CRC Press. p. 983. ISBN 0849330343.

- "Flavors and Extracts Manufacturers of the United States. Safety Assessment of Jambu Oleoresin, Washington, D.C.". FEMA: 12.

- Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food and Additives (2007). "Evaluation of certain food additives and contaminants. Flavoring Agents: Aliphatic and Aromatic Amines and Amides". World Health Organization Technical Report Series. 65 (947): 1–225. PMID 18551832.

- "Scientific Opinion on Flavouring Group Evaluation 303 (FGE.303): Spilanthol from chemical group 30". EFSA Journal. 9 (3): 1995. March 2011. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2011.1995.

- Moore, G.E. "28-Day dietary toxicity study in rodents. Study No. 11326. Product Safety Labs, East Brunswick, NJ. Unpublished report to the Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association of the United States, Washington, D.C., USA" (PDF). Retrieved 2 January 2014. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Tiwari, KL; SK Jadhav; V. Joshi (November 2011). "An updated review on medicinal herb genus Spilanthes". Journal of Chinese Integrative Medicine. 11. 9 (11): 1170–1178. doi:10.3736/jcim20111103. PMID 22088581.

- Chopra, R.N.; Nayar, S.L.; Chopra, I.C. (1956). "Glossary of Medicinal Plants". Council of Scientific & Industrial Research. New Delhi, India.

- Patel, V.K.; Patel, R.V.; Venkatakrishna-Bhatt, H.; Gopalakrishna, G.; Devasankariah, G. (1992). "A clinical appraisal of Anacyclus pyrethrum root extract in dental patients". Phytotherapy Research. 6 (3): 158–159. doi:10.1002/ptr.2650060313.

- Europe EP1861486A1, "A process of preparing jambu extract, use of said extract, cosmetic compositions comprising thereof and cosmetic products comprising said cosmetic compositions", issued 2017-05-17

- "Spilanthes acmella Seeds". Archived from the original on 2014-03-28. Retrieved 2014-03-28.

- Holetz, F. B.; et al. (2002). "Screening of some plants used in the Brazilian folk medicine for the treatment of infectious diseases". Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 97 (7): 1027–31. doi:10.1590/S0074-02762002000700017. PMID 12471432.

- Ratnasooriya, W. D.; et al. (2004). "Diuretic activity of Spilanthes acmella flowers in rats". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 91 (2–3): 317–20. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2004.01.006. PMID 15120455.

- Rani, S.A.; Murty, S.U. (2006). "Antifungal potential of flower head extract of Spilanthes acmella Linn". African J. Biomedical Research. 9: 67–68. doi:10.4314/ajbr.v9i1.48776.

- Boonen, J.; Roche, N.; Burvenich, C.; DeSpiegeler, B (2010). "Transdermal behavior of the N-alkylamide spilanthol (affinin) from Spilanthes acmella (Compositae) extract". Ethnopharmacology. 127 (1): 77–84. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2009.09.046. PMID 19808085.

- Boonen, J. B.; Roche, N.; Burvenich, C.; DeSpiegeler, B (2010). "LC-MS profiling of N-alkylamides in Spilanthes acmella extract and the transmucosal behavior of its main bio-active spilanthol". J. Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 53 (3): 243–249. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2010.02.010. PMID 20227845.

- Riera, C.E; Menozzi-Smarrito, C.; Affolter, M.; Michlig, S.; Munari, C.; Robert, F.; Vogel, H.; Simon, S.A.; le Coutre, J. (2009). "Compounds from Sichuan and Melegueta peppers activate, covalently and non-covalently, TRPA1 and TRPV1 channels". British Journal of Pharmacology. 157 (8): 1398–1409. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00307.x. PMC 2765304. PMID 19594761.

- Iwasaki, Y. Tanabe; Kobata, K.; Watanabe, T. (2008). "TRPA1 agonists – allyl isothiocyanate and cinnamaldehyde – induce adrenal secretion" (PDF). Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 72 (10): 2608–2614. doi:10.1271/bbb.80289. PMID 18838811.

- Savadi, RV; R Yadav; N Yadav (June 2010). "Study on immunomodulatory activity of ethanolic extract of Spilanthes acmella Murr. leaves" (PDF). CSIR: 204–207. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- Ramsewak, R. S.; et al. (1999). "Bioactive N-isobutylamides from the flower buds of Spilanthes acmella". Phytochemistry. 51 (6): 729–32. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(99)00101-6. PMID 10389272.

- Ley, J. P.; et al. (2006). "Isolation and synthesis of acmellonate, a new unsaturated long chain 2-ketol ester from Spilanthes acmella". Nat. Prod. Res. 20 (9): 798–804. doi:10.1080/14786410500246733. PMID 16753916.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Acmella oleracea. |