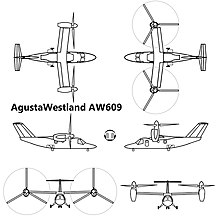

AgustaWestland AW609

The AgustaWestland AW609, formerly the Bell/Agusta BA609, is a twin-engined tiltrotor VTOL aircraft with a configuration similar to that of the Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey. It is capable of landing vertically like a helicopter while having a range and speed in excess of conventional rotorcraft. The AW609 is aimed at the civil aviation market, in particular VIP customers and offshore oil and gas operators.

| AW609 | |

|---|---|

| |

| AW609 in aeroplane mode at Paris Air Show 2007 | |

| Role | VTOL corporate transport |

| National origin | United States / Italy |

| Manufacturer | Bell/Agusta Aerospace AgustaWestland Leonardo |

| First flight | 6 March 2003 |

| Introduction | 2020 (expected) [1] |

| Status | Under development / flight testing |

Development

Origins and program changes

The BA609 drew on experience gained from Bell's earlier experimental tiltrotor, the XV-15.[2][3] In 1996, Bell and Boeing had formed a partnership to develop a civil tiltrotor aircraft; however, in March 1998, it was announced that Boeing had pulled out of the project. In September 1998, it was announced that Agusta had become a partner in the development program.[2] This led to the establishment of the Bell/Agusta Aerospace Company (BAAC), a joint venture between Bell Helicopter and AgustaWestland, to develop and manufacture the aircraft.[4] The Italian government subsidized Agusta's development of a military tiltrotor, and as the AW609 has civilian aspects, the European Commission requires AgustaWestland to pay back progressive amounts per aircraft to the Italian state to avoid a distortion of competition.[5] As of 2015, Bell continues to perform contract work on the AW609 program while considering commercial potential for the bigger V-280 tiltrotor, where military production may reach larger numbers and hence reduce unit cost.[6][7] However, in 2016, Bell preferred the 609 for commercial applications and kept the V-280 for military use only. Bell also stated that conventional helicopters were not part of Bell's future for military customers.[8]

The aircraft's purpose is to take off and land vertically, but fly faster than a helicopter.[9] Over 45 different aircraft have flown proving VTOL and STOL capabilities, of which the V-22, Harrier "jump jet" family, Yakovlev Yak-38 and Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II jets have proceeded to production.[10][11] By 2008, Bell had estimated that very light jets and large offshore helicopters like the Sikorsky S-92 had reduced the potential market for tiltrotors.[12] Also in 2008, it was reported that limited funding of the program by both Bell and AgustaWestland had resulted in slow flight testing progress.[13][14]

On 21 September 2009, AgustaWestland chief executive Giuseppe Orsi said that corporate parent Finmeccanica had authorised buying Bell Helicopter out of the program to speed it up,[15] as Bell was dissatisfied with the commercial prospects[16] and wanted to spend the resources on other programs.[13] In 2013 AgustaWestland estimated a market of 700 aircraft over 20 years.[17] By 2011, negotiations centred on the full transfer of technologies shared with the V-22,[14][18] however Bell stated that no technology was shared with the V-22.[13] At the 2011 Paris Air Show, AgustaWestland stated that it will assume full ownership of the programme, redesignating the aircraft as "AW609", and that Bell Helicopter will remain in the role of component design and certification.[19] In November 2011, the exchange of ownership was completed, following the granting of regulatory approval[20] - media estimated that the transfer happened at little cost.[21]

Testing

On 6 December 2002, the first ground tests of the BA609 prototype began, and the first flight took place on 6 March 2003 in Arlington, Texas, flown by test pilots Roy Hopkins and Dwayne Williams. After 14 hours of helicopter-mode flight testing, the prototype was moved to a ground testing rig to study the operational effects of the conversion modes.[22] Following the completion of ground-based testing, on 3 June 2005 the prototype resumed flight testing, focusing on the expansion of its flight envelope.[23] On 22 July 2005, the first conversion from helicopter to aeroplane mode while in flight took place.[24] By October 2008, 365 flight-hours had been logged by two prototype aircraft.[25] The AW609 demonstrated a safe dual-engine failure in normal cruise flight on 15 May 2009.[26] By February 2012, this had risen to 650 hours, and it was reported that 85 percent of the AW609's flight envelope had been explored.[20] Test pilot Paul Edwards has stated that the AW609 was not susceptible to the vortex ring state phenomena, naturally slipping out of the vortex on its own since both rotors will not simultaneously enter the vortex ring state.[27]

In 2011, AgustaWestland began construction of a third prototype; that prototype was still not fully assembled by February 2015. The company plans to conduct test flights in Italy in the summer of 2015. AgustaWestland planned to then disassemble it and ship it to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to prepare it for tests of the de-icing system in Minnesota. A fourth prototype, to be used in the development and testing of new avionics and control systems, was also underway.[28][29] By November 2012, over 700 flight hours had been accumulated by the two operational prototypes.[30] In January 2014, it was reported that in excess of 850 flying hours had been accumulated by the two prototypes; accumulated flight data is used to further develop representative simulators, which are in turn being used to support the development program.[31]

By March 2015, the two prototype aircraft had accumulated 1,200 hours (of about 2,000 hours necessary for certification[32]), and two more aircraft were expected to fly that year.[33] Flight test maximums had progressed to a weight of 18,000 lb (8,200 kg), a speed of 293 kn (337 mph; 543 km/h), and 30,000 ft (9,100 m) altitude.[34] In 2015, AgustaWestland reported that the AW609 flew 721 miles (1,161 km) from Yeovil, UK, to Milan, Italy, in 2 hours 18 minutes.[35] In September 2015, the first AW609 prototype was reportedly nearing the end of its service life, while a third prototype was finishing construction at the company's Vergiate facility and a fourth prototype was being built in Philadelphia.[27]

On 30 October 2015, the second of the two prototypes (N609AG) crashed near AgustaWestland's Vergiate facility in north west Italy, killing both pilots.[36]

Certification

_static_display_(21471922133).jpg)

In 2002, Type certification of the aircraft was projected for 2007,[37] while in 2007, certification was projected for 2011.[38] In August 2012, the aircraft was forecast to receive Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) certification in early 2016.[39] The company expects to achieve FAA certification in 2017.[40] Some delays were caused by lack of funding for the FAA,[41] others by the V-22 troubles,[42] while AgustaWestland also spent time increasing performance and reducing cost.[40]

In 2012, the FAA stated that the AW609 was to be certified in compliance with both helicopter and fixed-wing aircraft rules; additionally, new codes were to be developed to cover the transition phase between the two modes.[43] Of the 217 Pilot Training Tasks, 10 are unique tiltrotor tasks.[44] AW609 Certification Basis is established by FAA under the provisions of Part 21.17(b) for "Special Class Aircraft" along with a portion of Part 25 (fixed-wing aircraft) and 29 (helicopter) and new specific tiltrotor parts[45][43] in a new category called "powered lift".[40] In January 2013, the FAA defined US tiltrotor noise rules to comply with ICAO rules, expecting the AW609 to be available within 10 years. Noise certification will cost $588,000, which is the same as for a large helicopter.[46][47]

In February 2014, the AW609 was taken on its first customer demonstration flights, in both airplane and helicopter modes,[48][49] and began certification flights.[50]

In early summer 2014, the AW609 performed FAA-monitored autorotation tests; more than 79[32] power-off conversions from airplane mode to helicopter mode were made across 10 flight hours; during these tests it was stated that the minimum autorotation altitude is 3,000 ft (910 m), and that the system keeps rotor rpm above the minimum 70% for stable recovery.[51] The test pilots subsequently received the Iven C. Kincheloe Award for their role in the tests.[32][52]

Further developments

At the Farnborough Air Show in July 2012, AgustaWestland announced that it was to offer a higher-weight variant of the AW609 (up to 17,500 pounds or 7,900 kilograms[32]); this model would trade some of its vertical takeoff performance for increased payload capacity.[43] Officials from AgustaWestland have suggested that this short take off and vertical landing (STOVL) variant may be an attractive option for search and rescue and maritime operators.[53] According to senior vice-president of marketing Roberto Garavaglia, the Italian government is interested in acquiring several AW609s for coastal patrol duties; due to an agreement with Bell, these may not feature armament.[17][40]

In June 2013, AgustaWestland announced that work to integrate design changes as part of a major modernisation would delay the AW609's certification by up to one year.[54] These design changes primarily involved aerodynamic improvements, aimed at achieving a 10% reduction in drag and a significant reduction in overall weight, increasing the AW609's performance and capabilities. Separate improvement programs were underway on the aircraft's engines and avionics systems.[55][56] In 2015, AgustaWestland announced the development of external fuel tanks which would permit 800 nmi (920 mi; 1,500 km) flights carrying six passengers over three hours.[57]

In 2013, AgustaWestland was considering a US-based final assembly point for production AW609s; managing director Robert LaBelle stated that 35% of the customers for the tiltrotor are expected to come from the US market.[17] Reportedly, the primary production line was to be located in Italy while a second production line in the US was under consideration.[54] In 2015 AgustaWestland announced that the AW609 will be produced at its Philadelphia facility,[33][58] the production site for the AW139, AW119 KXe and AW169.[32] Two to three AW609 aircraft will be assembled there beginning in 2017, and once production matures, a second final assembly line is being considered for Italy.[32]

In 2015, Bristow Helicopters and AgustaWestland agreed to develop dedicated offshore oil and gas transport and search and rescue configurations for the AW609.[59] Bristow Group signed a joint development agreement with AgustaWestland at Heli-Expo on 3 March 2015 which will allow Bristow to exclusively direct the direction of the tiltrotor for offshore missions such as oil and gas operations.[60] The changes could extend beyond the AW609 to potentially affect the design of larger and more advanced models that AgustaWestland is planning to introduce in the early 2020s. The introduction of tiltrotors would allow for point-to-point operations, flying oil company personnel to platforms from major population centers with a greater margin of safety. Industry journalists viewed the agreement as an approval of the tiltrotor technology from the commercial industry, where previously only the military were interested.[11][60]

Design

The AW609 is a tiltrotor aircraft capable of performing vertical landings whereas conventional fixed-wing aircraft cannot, allowing the type to serve locations such as heliports or very small airports, while possessing twice the speed and the range of any available helicopter.[61] AgustaWestland promotes the type as "...combining the benefits of a helicopter and a fixed-wing aircraft into one aircraft".[62] The AW609 appears to be outwardly similar to the military-orientated V-22 Osprey; however, the two aircraft share few components. Unlike the V-22, the AW609 has a pressurised cabin.[61][63] As of 2013, multiple cabin configurations have been projected, including a standard nine-passenger layout, a six-to-seven-passenger VIP/executive cabin, and a search and rescue model featuring a hoist/basket and four single seats; medevac and patrol/surveillance-orientated variants has also been proposed.[64] For increased passenger comfort, the cabin is both pressurised and equipped with soundproofing.[62] Access to the cabin is via a 35-inch-wide (89 cm), two-piece clamshell door center-set into the fuselage underneath the wings.[32]

The AW609 is powered by a pair of Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6C-67A turboshaft engines, which each drive a three-bladed proprotor. These engines possess roughly twice the horsepower of the similarly sized AgustaWestland AW169 helicopter.[65] Both of the engine and proprotor pairs are mounted on a load-bearing rotatable pylon at the wing's ends, allowing the proprotors to be positioned at various angles. In helicopter mode, the proprotors can be positioned between a 75- and 95-degree angle from the horizontal, with 87 degrees being the typical selection for hovering vertically.[66] In airplane mode, the proprotors are rotated forward and locked in position at a zero-degree angle, spinning at 84% RPM.[31] The flight control software reportedly handles much of the complexity of the transitioning between helicopter and airplane modes;[31] automated systems also serve to guide pilots to the correct tilt angle and air speed settings.[66]

When flying in airplane mode, the majority of lift is produced by the AW609's wings, which are slightly forward-swept. Both the wing and the main fuselage are made largely of composite materials.[62] The 34-foot-long (10 m) wings feature flaperon control surfaces which are normally automatically controlled; in vertical flight, the flaperons drop to a 66-degree downwards angle to reduce the wing area being encountered by downwash from the proprotors. A high-mounted rudderless vertical stabiliser is attached the rear of the fuselage to stabilise flight while in aircraft mode.[66] In the event of a single engine failure, either engine can provide power to both proprotors via a drive shaft; the AW609 is also capable of autorotation.[39][63] The AW609 has been designed to develop Full Transport Category/Class 1 performance to operate safely even when flown under single engine conditions. It is equipped with a de-icing system, and is to be certified for flying into known icing conditions.[62] Building on experiences with the V-22, the AW609 is outfitted with a sink rate warning system.[67]

Avionics include a triple-redundant digital fly-by-wire flight control system, a head-up display system, and Full Authority Digital Engine Controls (FADEC). The cockpit has been designed so that the AW609 can be flown by a single pilot in instrument flight rules conditions.[39][68][69] Several of the aircraft's controls, such as blade pitch, are designed to resemble and function like their counterparts on conventional rotorcraft, enabling helicopter pilots to transition to the type more easily.[31][66] Elements of the aircraft's controls feature touchscreen interfaces.[62] Shortly following AgustaWestland's full acquisition of the program, a substantial modernisation of the AW609's design was initiated in 2012; these changes included new engines and the redesigning of the cockpit. As part of the design refresh, new flight management systems, Northrop Grumman inertial and GPS navigation systems, and various other avionics from Rockwell Collins were adopted.[54][70][71]

Operational history

Bell/Agusta aimed the aircraft "at the government and military markets".[72] Another key market for the AW609 has been the expansion of offshore oil and gas extraction operations, which requires aircraft capable of the traversing the increasing distances involved.[73] In 2001, Bell estimated a market for 1,000 aircraft.[74] Bell/Agusta stated in 2007 that they intend for the BA609 to compete with corporate business jets and helicopters, and that the BA609 would be of interest to any operator that has a mixed fleet of fixed wing and rotary wing aircraft.[75] In 2004, Lt. Gen. Michael Hough, USMC deputy commandant for aviation, requested that Bell conduct studies into arming the BA609, potentially to act as an escort for V-22s.[76] However, AgustaWestland's deal with Bell for taking over the BA609 program precludes the aircraft from carrying arms.[17][40]

In 2001, Terry Stinson, then chairman and CEO of Bell Helicopters, declared that costs will amount to "at least US$10 million".[77] In 2004, Don Barbour, then executive marketing director, stated that "early orders were taken at a price of between $8 and $10 million... since 1999, orders have been at a price to be confirmed no later than 24 months before aircraft delivery.[78] In 2012, industry reporters estimated that unit cost may come to $30 million,[20][79] while in 2015 some believed the price to be around $24 million.[32][33]

Orders were 77 in 1999,[80] and 70 in 2012, dependent on the final unit price.[79] As of March 2015, there are 60 orders for the AW609.[58] The company intends to have production facilities ready for completing orders right after FAA certification in 2017.[81]

Bristow Helicopters intends to order 10 or more.[82] Michael Bloomberg, the U.S. billionaire businessman and politician, is "near the top" of the list of buyers who have put a deposit down on the AW609 tiltrotor aircraft.[83] In February 2015, the Italian Army released a white paper documenting its vision of future procurement efforts, it included the intention to procure a force of tiltrotor aircraft for rapid troop-transport and medical evacuation duties; it has been speculated in the media that the AW609 is a likely candidate for the requirement.[84] On 10 November 2015, United Arab Emirates selected a search and rescue variant of the AW609, signing a memorandum of understanding three with an option for three more.[85] As of May 2019, no contract for the United Arab Emirates has been signed.[86]

Notable accidents and incidents

On 30 October 2015, the second of the two prototypes (N609AG), which first flew in 2006, crashed near AgustaWestland's Vergiate facility in North West Italy, killing long-time test pilots Pietro Venanzi and Herb Moran.[36][87] The aircraft broke up in midair after 27 minutes of flight, on a flight plan that included high speed testing.[88][89] Investigators consider the most likely cause to be changes in flight control laws and tail changes. These led to a "Dutch roll" instability while diving at 293 kn (337 mph; 542 km/h) where previously only 285 kn (328 mph; 528 km/h) had been achieved.[90][91][92] The Italian authorities seized the third prototype in May 2016,[93] and returned it for flight testing in July.[94]

The final report stated that during a high-speed dive with a left turn, "slight lateral-direction oscillations" started on roll-out and grew in amplitude and frequency. The pilot attempted to correct the roll with "counterphase input roll manoeuvres and then pedal inputs", but this did not dampen the oscillations. They instead became divergent, bringing the sideslip angle at 10.5°, well above the 4° maximum allowed, "inducing contact of the right proprotor with the right wing due to excessive flapping of the proprotor blades". This severed fuel and hydraulic lines in the wing leading edge, triggering a fire.[95][96]

Specifications (BA609)

Data from Jane's all the World's Aircraft 2004-05[97]The International Directory of Civil Aircraft, 2003–2004,[4] Jane's 2000, the BA609 and AW609 data sheets[72][98] and others[57][66][99]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2

- Capacity: 6 to 9 passengers or 5,500 lb (2,500 kg) payload

- Length: 13.4 m (44 ft 0 in)

- Wingspan: 10 m (32 ft 10 in) (distance between prop-rotor centres)

- Width: 18.3 m (60 ft 0 in) rotors turning

- Height: 4.6 m (15 ft 1 in) to top of fin

- Empty weight: 4,765 kg (10,505 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 7,620 kg (16,799 lb)

- Cabin height: 4 ft 8 in (1.42 m)

- Cabin width: 4 ft 10 in (1.47 m)

- Cabin length: 13 ft 5 in (4.09 m)

- Powerplant: 2 × Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6C-67A turboshaft engines, 1,447 kW (1,940 hp) each

- Main rotor diameter: 2× 7.9 m (25 ft 11 in)

- Main rotor area: 49 m2 (530 sq ft) each - 3-bladed prop-rotors

Performance

- Maximum speed: 509 km/h (316 mph, 275 kn)

- Cruise speed: 509 km/h (316 mph, 275 kn) maximum

- Range: 1,389 km (863 mi, 750 nmi) normal fuel + 2,500 kg (5,500 lb) payload at 463 km/h (288 mph; 250 kn)

- Ferry range: 1,852 km (1,151 mi, 1,000 nmi)

- Endurance: 3 hours with normal fuel

- Service ceiling: 7,620 m (25,000 ft)

- Hover Ceiling out of Ground Effect (HOGE): 1,525 m (5,003 ft)

- g limits: +3.1 -1

- Rate of climb: 7.616 m/s (1,499.2 ft/min) at sea level

- Disk loading: 77.4 kg/m2 (15.9 lb/sq ft) max

Avionics

- Rockwell Collins Pro Line 21 package, including:

- VOR

- DME

- ILS

- ADF

- dual VHF radios

- Rockwell Collins ALT-4000 radar altimeter

- GPS

- TCAS

- FDR

- 3x LCD displays with standby instruments

- Rockwell Collins WXR-800 solid-state weather radar

See also

Related development

Related lists

References

- https://www.verticalmag.com/news/leonardo-focusing-on-first-delivery-of-aw609-as-it-enters-mass-production/

- Maisel, Martin D.; Giulianetti, Demo J.; Dugan, Daniel C. (2000). The History of the XV-15 Tilt Rotor Research Aircraft (PDF). Monographs in Aerospace History No. 17. NASA. ISBN 0-16-050276-4. NASA SP-2000-4517.

- "XV-15 Completes Demonstration On Coast Guard Cutter" Helicopter News via HighBeam, 2 July 1999. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- Frawley, Gerard (2003). The International Directory of Civil Aircraft, 2003–2004. Aerospace Publications. p. 48. ISBN 1-875671-58-7.

- "State aid: Commission agrees with Italy amount of subsidies Augusta Westland needs to reimburse for projects that have civilian uses". States News Service. 12 January 2011. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2015 – via HighBeam Research.

- Black, Thomas. "Bell Helicopter exploring civilian market for new tilt-rotor aircraft" Archive

- "Helicopter market eyes civilian tilt-rotor models". Financial Times. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- "HELI-EXPO: Bell rules out future conventional military helicopter developments". Flightglobal.com. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- Venanzi & Wells 2013, p. 5.

- Venanzi & Wells 2013, p. 37.

- Osborne, Tony (6 March 2015). "Podcast: Exciting And Strange Developments From Heli-Expo". Aviation Week & Space Technology. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- McKenna, James T. (15 March 2008). "Are the S-92 and Light Jets Shrinking the BA609 Market?". Rotor & Wing. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2015 – via HighBeam Research.

- Huber, Mark (30 June 2011). "AgustaWestland Buys Bell's Stake in BA609 Tiltrotor". Aviation International News. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- Osborne, Tony (5 March 2011). "Heli-Expo 2011: AgustaWestland to take over BA609 tiltrotor project". Shephard Media. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- Peruzzi, Luca (21 September 2009). "AgustaWestland looks to take full control of BA609 civil tiltrotor programme". Flight International. Retrieved 14 February 2012 – via FlightGlobal.com.

- Skinner, Tony (29 November 2011). "AgustaWestland and Bell complete 609 transaction". Shephard Media. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- Huber, Mark (1 January 2013). "AgustaWestland AW609 Moves Forward, May Be Built in Texas". Aviation International News.

- Trimble, Stephen (14 March 2011). "Bell, AgustaWestland disagree on future of BA609 partnership". Flight International. Retrieved 14 February 2012 – via FlightGlobal.com.

- "AgustaWestland Takes Full Ownership of the BA609 Programme" (Press release). AgustaWestland. 21 June 2011. Archived from the original on 27 June 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- Wynbrandt, James (11 February 2012). "AW609 Finally Ready for its Close-up". Aviation International News. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- Huber, Mark (3 January 2012). "Finmeccanica Slide Could Impact New AgustaWestland Programs". Aviation International News. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- "BA609 Ground Runs Convert Helicopter To Airplane". VTOL.org. American Helicopter Society. March 2005. Archived from the original on 27 September 2006.

- "Bell Returns BA609 to Test Flight". VTOL.org. American Helicopter Society. June 2005. Archived from the original on 27 September 2006.

- "BA609 Tilt Rotor Makes Airplane Conversion". VTOL.org. American Helicopter Society. July 2005. Archived from the original on 27 September 2006.

- Padfield, R. Randall (7 October 2008). "BA609 Civil Tiltrotor Still on Schedule". Aviation International News. Archived from the original on 16 October 2008. Retrieved 20 October 2008.

- Venanzi & Wells 2013, p. 32.

- Perry, Dominic (16 September 2015). "AgustaWestland prepares for AW609 certification push". Flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015.

- Sarsfield, Kate (6 December 2011). "AgustaWestland at full tilt to deliver AW609 on time". Flight International. 180 (5320): 18.

- Osbourne, Tony (2–15 March 2015). "Tilting times". Aviation Week & Space Technology: 52–3.

- Morrison, Murdo (13 November 2012). "In focus: AgustaWestland exploits buoyant civil helicopter mark". Flight International via FlightGlobal.com.

- Head, Elan (20 January 2014). "Flying the AW609: A Preview". Vertical. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- Huber, Mark (3 March 2015). "AgustaWestland to build AW609 in Philadelphia". Aviation International News. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Niles, Russ (3 March 2015). "Tiltrotor Production Planned". AVweb. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- Erdos, Rob (5 March 2015). "AW609 Tiltrotor Making Strides Toward Certification". Vertical Magazine. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- "The AW609 TiltRotor sets speed record on 1000 km journey: 2 hours 18 minutes from UK to Italy" (Press release). Finmeccanica. 15 September 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- Perry, Dominic (30 October 2015). "AW609 crash kills two pilots in northern Italy". FlightGlobal.com.

- "Bell aiming for BA609 certification in 2007", Flightglobal, Reed Business Information, 8 October 2002, archived from the original on 8 March 2015, retrieved 8 March 2015

- Cox, Mike; Hubbard, Greg (18 June 2007). "BAAC 609 Flight Test Continues Development Pace" (Press release). Bell Helicopter. Archived from the original on 15 July 2007.

- Thurber, Matt (2 August 2012). "AgustaWestland Taps P&WC, Rockwell Collins and BAE for AW609 Civil Tiltrotor". Aviation International News.

- Osborne, Tony (2 December 2013). "Certification Flight-Test Work Nears For AW609". Aviation Week & Space Technology. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- Sutton, Oliver (16 June 2000). "FAA inaction threatens civilian tiltrotors". Helicopter News. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2015 – via HighBeam Research.

- Fairbank, Katie (13 January 2003). "New aircraft will be 1st commercial tilt-rotor". The Dallas Morning News. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2015 – via HighBeam Research.

- Dubois, Thierry (9 July 2012). "AgustaWestland Offers Higher Weight AW609 Option". Aviation International News. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- Venanzi & Wells 2013, p. 16.

- Venanzi & Wells 2013, p. 17.

- Federal Aviation Administration (8 January 2013). "Noise Certification Standards for Tiltrotors". Federal Register. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- "FAA Publishes Modified Noise Rules For Tiltrotors". Aero-News Network. 11 January 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- Wynbrandt, James (26 February 2014). "AgustaWestland Offers Demo Flights on AW609 Tiltrotor at Heli-Expo 2014". Aviation International News. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- "AgustaWestland Completes First Customer Demonstration of AW609" (Press release). AugustaWestland. 27 February 2014. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Osborne, Tony (25 February 2014). "AW609 Begins Certification Flying". Aviation Week & Space Technology. Archived from the original on 17 August 2014. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- Huber, Mark (2 June 2014). "Test Pilot's Take on Autorotating the Tiltrotor". Aviation International News. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- "AW609 Test Pilots Receive Iven C. Kincheloe Award" (Press release). AgustaWestland. 21 October 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- Croft, John (7 February 2012). "In focus: Global demand grows for helicopters able to access remote oil and gas fields". Flight International via FlightGlobal.com.

- Perry, Dominic (10 June 2013). "AgustaWestland AW609 certification slips to 2017". Flight Internationals via FlightGlobal.com.

- Perry, Dominic (13 September 2013). "AgustaWestland tests enhancement package on AW609". Flight International. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- "AgustaWestland AW609 TiltRotor Aerodynamic Improvements Set To Boost Performance" (Press release). AgustaWestland. 3 September 2013. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014.

- "AgustaWestland Announces Further AW609 TiltRotor Performance and Product Improvements" (Press release). AgustaWestland. 3 March 2015. Archived from the original on 31 March 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- "AgustaWestland Begins Production Phase of AW609 Tiltrotor". Aviation Today. 3 March 2015. Archived from the original on 5 March 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- "AgustaWestland and Bristow Sign Exclusive Platform Development Agreement for the AW609 Tiltrotor Program". Vertical (Press release). AgustaWestland. 3 March 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- Osborne, Tony (6 March 2015). "Bristow Taps Tiltrotors For Future Needs". Aviation Week. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- Aston, Adam (22 October 2007). "Selling CEOs on a Troubled Bird". BusinessWeek. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- "AW609: Convertiplane". Leonardo. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Stephens, Ernie (28 April 2014). "Pilot Report: Flying the AW609". Aviation Today. Archived from the original on 20 May 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- Huber, Mark (4 March 2013). "AW609 Program Accelerating Under AgustaWestland". Aviation International News.

- de Briganti, Giovanni (4 December 2012). "AgustaWestland Completes AW609 Tiltrotor Takeover". Defense-aerospace.com. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- Stephens, Ernie (1 December 2014). "The AW609 Tilt Rotor: 2014's Best Ride". Aviation Today. Archived from the original on 2 December 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- Venanzi & Wells 2013, p. 20.

- Trautvetter, Chad (12 July 2012). "AgustaWestland Names Three Key Suppliers For AW609 Civil Tiltrotor". Aviation International News. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- "Rockwell Collins' Pro Line Fusion selected for AW609". Shephard Media. 26 October 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- "AgustaWestland AW609 TiltRotor Aerodynamic Improvements Set To Boost Performance" (Press release). AgustaWestland. 3 September 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- "Northrop Grumman Provides Inertial Navigation Products for TiltRotor Vertical Take-off and Landing Aircraft" (Press release). Northrop Grumman. 24 February 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- "Products: BA609". AgustaWestland. Archived from the original on 6 June 2010.

- Kay, Marcia Hillary (1 August 2007). "40 Years Retrospective: It's Been a Wild Ride". Rotor & Wing. Archived from the original on 8 June 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- Keeter, Hunter (22 May 2001). "BA609 Team Confident V-22 Woes Won't Hurt Program, Will Apply Lessons". Defense Daily. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2015 – via HighBeam Research.

- Croft, John (15 February 2008). "Civil rotorcraft special: Rotorcraft makers strive to break the civil rotorcraft 'speed limit'". Flight International via FlightGlobal.com. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- "Bell asked to come up with a tilt-rotor gunship to escort V-22s". Dallas Business Journal. 6 July 2004. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- Cowan, Rory (2001). "Bell Takes 'Cautious' Stance on Economy". Aviation Week. Retrieved 10 October 2009.

- "Bell Augusta: BA609". Aviation International News. 2004. Archived from the original on 23 February 2004.

- Dubois, Thierry; Huber, Mark (February 2012). "New Rotorcraft 2012" (PDF). Aviation International News. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

...is now believed to have soared to $30 million.

- Sarsfield, Kate (6 October 1999), "Bristow order launches AB139", Flightglobal, Reed Business Information, archived from the original on 8 March 2015, retrieved 8 March 2015

- Head, Elan (25 April 2014). "AgustaWestland completes autorotation trials for AW609 program". Vertical. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Huber, Mark (3 March 2015). "Bristow Commits To Being Partner and Customer for AW609 Civil Tiltrotor". Aviation International News. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Haughney, Christine; Grynbaum, Michael M. (13 April 2012). "In His Helicopter, Bloomberg Can Rule Skies, and Even Get to Albany". The New York Times. p. A1. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- Kington, Tom. "Italian Army Lays Out Future Vision." Defense News, 14 January 2015.

- Mustafa, Awad; Mehta, Aaron (10 November 2015). "UAE Picks AW609 for Tiltrotor Requirement". www.defensenews.com. TEGNA. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- Jennings, Gareth (31 May 2019). "UAE deal for AW609 tiltrotors looks in doubt". Jane's 360. London. Archived from the original on 31 May 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- Johnson, Oliver (30 October 2015). "AW609 prototype crashes; both pilots killed". Vertical. Archived from the original on 3 November 2015.

- Johnson, Oliver (9 November 2015). "AgustaWestland: AW609 was performing high-speed tests on day of crash". Vertical.

- "AW609 Broke Up in Midair; Int'l Team Seeks Clues". Rotor & Wing International. 16 December 2015.

- Perry, Dominic (24 June 2016). "AW609 control laws initiated 'Dutch roll': investigators". FlightGlobal. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- Head, Elan (25 June 2016). "AW609 flight control laws may have contributed to fatal accident". Vertical. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- "Tronzano Vercellese (VC), AW609 registration marks N609AG: Interim Statement". Agenzia Nazionale per la Sicurezza del Volo. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- Jennings, Gareth (26 May 2016). "Italian authorities seize AW609 prototype as investigations into fatal crash continue". IHS Jane's Defence Weekly. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- Head, Elan (12 July 2016). "Third AW609 prototype returned to Leonardo". Vertical. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- Perry, Dominic (10 May 2017). "Flawed flight-control logic triggered AW609's in-flight break-up: report". FlightGlobal. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- "Tronzano Vercellese (VC), AW609 registration marks N609AG; Final Report". Agenzia Nazionale per la Sicurezza del Volo. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- Jackson, Paul, MRAeS, ed. (2005). Jane's all the World's Aircraft 2004-05. London: Jane's Publishing Group. ISBN 0-7106-2614-2.

- "AW609 Tiltrotor" (PDF). AgustaWestland. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 April 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- "Agusta Westland AW609 Tiltrotor". Aeroglob. Archived from the original on 14 April 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

Bibliography

- Venanzi, Pietro; Wells, Dan (November 2013). AW609 TiltRotor Flight Test Program Overview (PDF). 2013 Flight Test Symposium. November 2013. Fort Worth, Texas. AgustaWestland. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Acree, Jr., Cecil W.; Johnson, Wayne R. (2006). Performance, Loads and Stability of Heavy Lift Tiltrotors (PDF). AHS Vertical Lift Aircraft Design Conference. 18–20 January 2006. San Francisco, California. NASA. 20060013409. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to AgustaWestland AW609. |

- AgustaWestland AW609 at LeonardoCompany.com

- AW609 promotional video by AgustaWestland at YouTube.com

- Video of VIP and Rescue interiors, interview with test pilot by AVweb