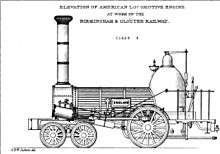

4-2-0

Under the Whyte notation for the classification of steam locomotives, 4-2-0 represents the wheel arrangement of four leading wheels on two axles, two powered driving wheels on one axle and no trailing wheels. This type of locomotive is often called a Jervis type, the name of the original designer.

Front of locomotive at left | |||||||||||||||||||||||

_(14760246992).jpg) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Overview

The 4-2-0 wheel arrangement type was common on United States railroads from the 1830s through the 1850s. The first 4-2-0 to be built was the Experiment, later named Brother Jonathan, for the Mohawk and Hudson Railroad in 1832. It was built by the West Point Foundry based on a design by John B. Jervis. Having little else to reference, the manufacturers patterned the boiler and valve gear after locomotives built by Robert Stephenson of England. A few examples of Stephenson locomotives were already in operation in America, so engineers did not have to travel too far to get their initial ideas.

In England, the 4-2-0 was developed around 1840 from the 2-2-2 design of Stephenson's first Long Boiler locomotive, which he had altered to place two pairs of wheels at the front to improve stability, with the outside cylinders between them.

In the United States, the design was a modification of the 0-4-0 design, then in common use. The 0-4-0 proved to be too rigid for the railroads of the day, often derailing on the tight curves and rapid elevation changes of early American railroads. For the 4-2-0, Jervis introduced a four-wheel leading truck under the locomotive's smokebox. It swiveled independently from the main frame of the locomotive, in contrast to the English 4-2-0 engines which had rigid frames. The pistons powered a single driving axle at the rear of the locomotive, just behind the firebox. This design resulted in a much more stable locomotive which was able to guide itself into curves more easily than the 0-4-0.[1][2]

This design proved so effective on American railroads that many of the early 0-4-0s were rebuilt as 4-2-0s. The 4-2-0 excelled in its ability to stay on the track, especially those with the single driving axles behind the firebox, whose main virtue was stability. However, with only one driving axle behind the firebox, the locomotive's weight was spread over a small proportion of powered wheels, which substantially reduced its adhesive weight. On 4-2-0 locomotives which had the driving axle in front of the firebox, adhesive weight was increased. While this plan placed more of the locomotive's weight on the driving axle, it reduced the weight on the leading truck which made it more prone to derailments.[1][2]

One possible solution was patented in 1834 by E.L. Miller and used extensively by Matthias W. Baldwin. It worked by raising a pair of levers to attach the tender frame to an extension of the engine frame, which transferred some weight from the tender to the locomotive frame and increased the adhesive weight. An automatic version was patented in 1835 by George E. Sellers and was used extensively by locomotive builder William Norris after he obtained rights to it. This system used a beam whose fulcrum was the driving axle. On flat and level surfaces, the beam would be slightly raised, but upon starting or on grades, the resistance made the beam assume a horizontal position which caused the locomotive to tip upward.[1][2]

A more practical solution, first put into production by Norris, relocated the driving axle to a location on the frame in front of the locomotive's firebox. This was done because Baldwin refused to grant rights to Norris to use his patented "half-crank" arrangement. Cantilevering the weight of the firebox and the locomotive crew behind the driving axle placed more weight on the driving axle without substantially reducing the weight on the leading truck. However, Norris's design led to a shorter wheelbase, which tended to offset any gains in tractive force on the driving axle by reducing the locomotive's overall stability. A number of Norris locomotives were imported into England for use on the Birmingham and Bristol Railway since, because of the challenges presented by the Lickey Incline, British manufacturers declined to supply.[1][2]

Once steel became available, greater rotational speeds became possible with multiple smaller coupled wheels. Five years after new locomotive construction had begun at the West Point Foundry in the United States with the 0-4-0 Best Friend of Charleston in 1831, the first 4-4-0 locomotive was designed by Henry R. Campbell, at the time the chief engineer for the Philadelphia, Germantown and Norristown Railway. Campbell received a patent for the design in February 1836 and soon set to work building the first 4-4-0. For the time, Campbell's 4-4-0 was a giant among locomotives. Its cylinders had a 14 inches (356 millimetres) bore with a 16 inches (406 millimetres) piston stroke, it boasted 54 inches (1,372 millimetres) diameter driving wheels, could maintain 90 pounds per square inch (620 kilopascals) of steam pressure and weighed 12 short tons (10.9 tonnes). Campbell's locomotive was estimated to be able to pull a train of 450 short tons (410 tonnes) at 15 miles per hour (24 kilometres per hour) on level track, outperforming the strongest of Baldwin's 4-2-0s in tractive effort by about 63%. However, the frame and driving gear of his locomotive proved to be too rigid for the railroads of the time, which caused Campbell's prototype to be derailment-prone.[1][2]

As the 1840s approached and more American railroads began to experiment with the new 4-4-0 locomotive type, the 4-2-0 fell out of favor since it was not as able as the 4-4-0 to pull a paying load. 4-2-0s continued to be built into the 1850s, but their use was restricted to light-duty trains since, by this time, most railroads had found them unsuitable for regular work.[1][2]

In England, for freight work, four-coupled and six-coupled engines were performing well. However, for passenger work the aim was greater speed. Because of the fragility of cast-iron connecting rods, "singles" continued to be used, with the largest driving wheels possible.

For some reason, British manufacturers did not take up the idea of mounting the forward wheels on a bogie for some years. There were possibly fears about their stability and with a long rigid frame, greater speed was achieved, albeit at the cost of a very rough ride and damage to the track. The culmination of this approach was seen in the Crampton locomotive where, to make the driving wheels as large as possible, they were mounted behind the firebox.[1][2][3]

Usage

South Africa

In 1923, the South African Railways conducted trials with a prototype petrol-paraffin powered road-rail tractor and, in 1924, placed at least two Dutton steam road-rail tractors in service on the new 2 ft (610 mm) narrow gauge line between Naboomspruit and Singlewood in Transvaal. The petrol-paraffin prototype and one of the latter had a 4-2-0 wheel arrangement.[4][5]

The prototype was a modified Dennis tractor which was fitted with a removable bogie between the front wheels to lift them high enough to prevent ground contact. A ball pin on the bogie fit into a socket in the front axle, and the bogie could easily be removed or replaced by running the tractor up a pair of ramps, placed on both sides of the track.[4][6][7][8]

The production model was a modified Yorkshire steam tractor, fitted with jacks at the front to allow a separate bogie to be manoeuvred into position underneath the front axle to guide it on the rails. Without the bogie, the vehicle could still be driven on ordinary roads and had the advantage of being able to be detached and run around the train, without requiring special loops for that purpose. For reversing on the track, as when shunting, the rear wheels were modified to be steerable.[5][9]

United States of America

The first railroad locomotive to operate in Chicago, Illinois was a 4-2-0, the Pioneer, which was built in 1837 by Baldwin Locomotive Works for the Utica and Schenectady Railroad in New York. It was later purchased used by William B. Ogden for the Galena and Chicago Union Railroad, the oldest predecessor of the Chicago and North Western Railway. The locomotive arrived in Chicago by schooner on 10 October 1848 and it pulled the first westbound train out of the city fifteen days later, on 25 October 1848.[10]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 4-2-0. |

- White, John H. Jr. (1968). A history of the American locomotive; its development: 1830–1880. New York, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-23818-0.

- Kinert, Reed (1962). Early American steam locomotives; 1st seven decades: 1830-1900. Seattle, WA: Superior Publishing Company.

- Comstock, Henry B. (1971). The Iron Horse. Toronto, Canada: Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited.

- Espitalier, T.J.; Day, W.A.J. (1945). The Locomotive in South Africa - A Brief History of Railway Development. Chapter VII - South African Railways (Continued). South African Railways and Harbours Magazine, October 1945. pp. 782-783.

- Paxton, Leith; Bourne, David (1985). Locomotives of the South African Railways (1st ed.). Cape Town: Struik. pp. 118–119. ISBN 0869772112.

- Stronach-Dutton Road-Rail - The Roadrail System of Traction

- Transport Problems in South Africa - The Dutton Loco-Tractor Advocated as a Solution. Article in The Commercial Motor, 24 August 1920. p. 14.

- Important Development Roadrail Transport. Article in Commercial Motor, 26 September 1922. pp. 168-169.

- Patent: Dutton Light Railway System and Locomotive Therefor, US 1306051 A, Jun 10, 1919

- SteamLocomotive.com - Chicago Area Steam The Illinois Railway Museum Archived 2018-07-13 at the Wayback Machine (Accessed on 22 August 2016)