32nd Texas Cavalry Regiment

The 32nd Texas Cavalry Regiment, sometimes incorrectly named Andrews's 15th Texas Cavalry Regiment,[1] was a unit of volunteer cavalry mustered into the Confederate States Army in May 1862 and which fought during the American Civil War. The regiment was formed around companies from Richard Phillip Crump's 1st Texas Cavalry Battalion which fought in Indian Territory and at Pea Ridge. Many of the soldiers died of disease in the unhealthy camps near Corinth, Mississippi. The cavalrymen were dismounted in July 1862 and served as infantry for the rest of the war. The regiment fought at Richmond, Ky., Stones River, and Chickamauga in 1862–1863, in the Meridian and Atlanta campaigns and at Nashville in 1864, and at Spanish Fort and Fort Blakeley in 1865. The regiment's 58 surviving members surrendered to Federal forces on 9 May 1865.

| 32nd Texas Cavalry Regiment | |

|---|---|

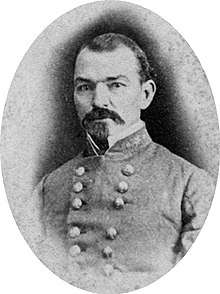

.jpg) Lieutenant Colonel Julius A. Andrews | |

| Active | May 1862 – 9 May 1865 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Cavalry, Infantry |

| Size | Regiment |

| Equipment | Rifled musket |

| Engagements |

|

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Julius A. Andrews |

History

Formation

The 32nd Texas Cavalry was accepted into Confederate service in May 1862 at Corinth. It was formed from companies that formerly belonged to Richard Phillip Crump's 1st Texas Cavalry Battalion. The unit that became Company G of the 32nd Texas Cavalry fought at the Battle of Chustenahlah on 26 December 1861.[1] On 7–8 March 1862, the 1st Texas Cavalry Battalion fought at the Battle of Pea Ridge as part of James M. McIntosh's cavalry brigade.[2] On the first day, the battalion participated in a cavalry charge that drove off two Federal cavalry regiments and seized three cannons.[3] The deaths of McIntosh and his superior Benjamin McCulloch early in the battle led to a loss of command control. This caused many Confederate units to remain idle for most of the day. In the afternoon, Albert Pike finally took command and led several units to join the other half of the army, but the 1st Texas Battalion and other units marched back to camp and out of the battle.[4]

Georgia native Julius A. Andrews first enlisted as a sergeant major in the 1st Louisiana Battalion at age 21. He was soon released and went to Texas where he joined Crump's battalion as Adjutant. When the 32nd Texas Cavalry was formed in May 1862, Andrews was elected colonel. The other elected field officers were Lieutenant Colonel James A. Weaver of Hopkins County and Major William E. Estes of Bowie County.[1]

1862–1863

During its stay in disease-ridden camps during the Siege of Corinth, the 32nd Texas Cavalry suffered the deaths of more than 150 men from measles, pneumonia, chronic diarrhea, and other illnesses. Other soldiers became so debilitated that they were discharged from service. The regiment was assigned to the brigade of Joseph L. Hogg along with the 10th Texas, 11th Texas, and 14th Texas Cavalry Regiments. Hogg soon died and was replaced by T. H. McCray as brigade commander. In July 1862, the regiment was dismounted and served the remainder of the war as an infantry unit. The other regiments of the brigade were also dismounted around this time. McCray's brigade was transferred to Edmund Kirby Smith's forces.[1]

In late August, Smith's forces advanced toward Lexington, Kentucky.[5] Opposing them were two brigades under William "Bull" Nelson. After a day of skirmishing, Patrick Cleburne's division was reinforced by a second Confederate division under Thomas James Churchill, which included McCray's brigade.[6] The Battle of Richmond began when Cleburne encountered Mahlon Dickerson Manson's Union brigade near Mount Zion Church.[7] McCray's brigade arrived and began attacking the Federal right flank.[6] McCray's brigade was deployed with the 10th, 11th, 14th, and 32nd (15th) Texas Cavalry, and the 31st Arkansas Infantry Regiment, going from left to right.[7] Though Charles Cruft's Union brigade soon arrived, the Confederates practically annihilated the Federals, inflicting losses of 206 killed, 844 wounded, and 4,303 captured on a force that counted 6,500 soldiers. The Confederates sustained losses of 78 killed, 372 wounded, and one missing out of 6,850 troops engaged.[6] According to another source, the 32nd Texas lost five killed, including two captains, at least six wounded, and 13 captured.[1]

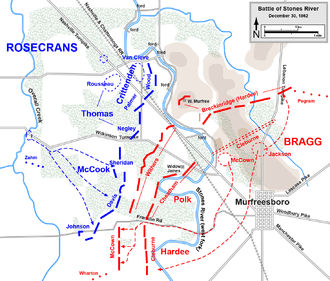

In the Battle of Stones River on 31 December 1862–2 January 1863, the brigade was commanded by Mathew Ector. The brigade no longer included the 31st Arkansas.[8] Douglas's Texas Battery was attached to the brigade.[9] McCown's division attacked the Federal right flank at dawn on the first day with the brigades of James Edwards Rains on the left, Ector in the center, and Evander McNair on the right. The assault took the Union troops completely by surprise. Ector's brigade defeated August Willich's Union brigade and captured its commander. Within minutes McCown's victorious Confederates captured eight artillery pieces and 1,000 Federals.[10] By chasing after the routed Union troops, Rains's brigade swung too far to the left. Ector aligned his brigade with Rains's soldiers and the two generals soon found that McNair's brigade was nowhere in sight. With McCown's troops too far to the left, Cleburne's division of the second line soon found itself in the front line.[11]

Later in the morning McCown reassembled his brigades and allowed the men to replenish their ammunition. McCown then ordered Rains to shift his brigade to the division's right flank attack to the northeast.[12] As Rains's troops burst out of the woods into the open ground near the Nashville Pike, they ran into a concentration of rallied Federal troops. Rains was killed and his brigade repulsed.[13] McCown was unable to coordinate his brigades and Ector's brigade became the next unit to challenge the Union defenses near the turnpike. Colonel Andrews soon found his own regiment and the 14th Texas Cavalry in an unequal battle with Samuel Beatty's Federal brigade. Andrews convinced Ector to withdraw and the two regiments pulled back into the woods. While the 14th and 32nd were pursued into the trees, other Federal troops compelled the 10th and 11th Texas Cavalry to pull back.[14] Ector's brigade reported losing 28 killed, 276 wounded, and 48 missing at Stones River.[9] The 32nd Texas Cavalry lost five killed, 36 wounded, and three missing. In summer 1863, Ector's brigade transferred to Mississippi in a futile attempt to relieve the Siege of Vicksburg.[1] After Stones River, the 11th Texas Cavalry was remounted and transferred to another brigade.[15]

For the Battle of Chickamauga on 19–20 September 1863, Ector's brigade served in States Rights Gist's division in William H. T. Walker's corps. Ector's brigade was made up of Stone's Alabama and Pound's Mississippi Sharpshooter Battalions, the 29th North Carolina Infantry Regiment, the 9th Texas Infantry Regiment, and the 10th, 14th, and 32nd Texas Cavalry.[16] Early on 19 September, John T. Croxton's Federal infantry brigade came into contact with Henry Brevard Davidson's Confederate cavalry brigade. Nathan Bedford Forrest was at hand and he rapidly sent infantry brigades under Claudius C. Wilson and Ector into the expanding conflict. Along the Reed's Bridge Road, Ector's troops came up against Ferdinand Van Derveer's Union brigade. Ector withdrew his troops from the unequal contest after 30 minutes because his troops lacked effective artillery support.[17] Ector and Wilson took such serious losses on the first day that their brigades were reduced to about 500 men each. On 20 September, Gist's division was ordered into action with Peyton H. Colquitt's 980 soldiers in the front line and Ector's and Wilson's men in a supporting line. The attack was repulsed with heavy losses and Colquitt was killed. Ector's and Wilson's troops covered the retreat of Colquitt's survivors.[18] Ector's brigade suffered losses of 59 killed, 239 wounded, and 138 missing.[19] Chickamauga was the worst experience of the war for the 32nd Texas Cavalry. Out of 217 officers and men, the regiment lost 13 killed, 65 wounded, and 40 missing. Andrews was badly wounded in the thigh.[1]

1864–1865

After Chickamauga, Ector's brigade transferred to Mississippi where it joined the division of Samuel Gibbs French in Leonidas Polk's corps. The brigade participated in the Meridian campaign in early 1864.[15] For the Atlanta Campaign, Ector's brigade included the 29th and 39th North Carolina Infantry, the 9th Texas Infantry, Jacques's Battalion, and the 10th, 14th, and 32nd Texas Cavalry.[20] On 19 May 1864, French's division joined Joseph E. Johnston's army with 4,174 soldiers.[21] In the Atlanta Campaign, the 32nd Texas Cavalry lost 11 killed and 35 wounded. The brigade fought at Cassville, New Hope Church, Latimer's Farm, Peachtree Creek, Atlanta, and Lovejoy's Station. At the Battle of Allatoona on 5 October 1864, the regiment was assigned to guard the artillery and missed this bloody action. However, Captain Somerville of the regiment led a raid on a Union warehouse in which he was wounded in the stomach and left for dead. Somerville was captured and nursed back to health by the Federal doctors, dying in 1917. Colonel Andrews succeeded to command of the brigade after Allatoona.[1] Ector was wounded during the Atlanta campaign and lost his leg, though he later rejoined the army.[22]

During John Bell Hood's invasion of Tennessee, Ector's brigade missed the Battle of Franklin since it was guarding the army's pontoon bridges. Colonel Andrews was badly wounded on 4 December 1864 and left the army to recover.[1] The 32nd Texas Cavalry was commanded by Major Estes during the Battle of Nashville on 15–16 December. Ector's brigade was part of Alexander P. Stewart's corps and led by Colonel D. Coleman.[23] The regiment lost at least four wounded and 13 captured at Nashville. Ector's brigade, now reduced to only about 500 soldiers, formed part of the army's rearguard during the retreat after Nashville. In January 1865, Estes, Quartermaster John S. Fowlkes, and Surgeon High G. McClarty were furloughed.[1]

Ector's brigade defended Mobile, Alabama in the spring of 1865. Edward Canby commanded 45,000 Union troops while Dabney H. Maury led 10,000 Confederate soldiers and 300 cannons. In the Battle of Spanish Fort two divisions of the Union XIII Corps under Gordon Granger on the left and two divisions of the Union XVI Corps under Andrew Jackson Smith on the right invested the fort. The fort was defended by the brigades of Ector, James T. Holtzclaw, and Randall L. Gibson, from left to right. After Union troops seized a foothold, the fort was evacuated on the night of 8–9 April 1865 with the loss of about 50 guns and 500 prisoners.[24] The next day, in the Battle of Fort Blakeley, the Federals launched a massive assault and overran the fortifications. The Union troops lost 113 killed and 516 wounded while 3,423 Confederate troops were captured. The 4,500 survivors of Maury's command retreated toward Montgomery, Alabama.[25] The 32nd Texas Cavalry lost seven wounded and 28 captured in the fighting.[1]

Nine officers and 49 rank and file of the 32nd Texas Cavalry under the command of Brevet Major Nathan Anderson marched to Meridian where they surrendered on 9 May 1865. Over 1,000 men served with the regiment during the war. Captain Travis C. Henderson of G Company later served in the Texas state legislature. Francis A. Taulman of G Company became mayor of Hubbard, Texas. The Estes brothers helped found the city of Texarkana, Texas. Cullen Montgomery Baker of Company I became a notorious outlaw and killer. Colonel Andrews moved several times and died at 90 years of age in 1930.[1]

Notes

- Bell 2013.

- Shea & Hess 1992, p. 335.

- Shea & Hess 1992, p. 99.

- Shea & Hess 1992, pp. 142–146.

- Cozzens 1991, p. 4.

- Boatner 1959, pp. 697–698.

- American Battlefield Trust 2019.

- Cozzens 1991, p. 231.

- Battles & Leaders 1987a, p. 612.

- Cozzens 1991, pp. 85–88.

- Cozzens 1991, pp. 89–91.

- Cozzens 1991, pp. 134–135.

- Cozzens 1991, pp. 139–141.

- Cozzens 1991, pp. 144–146.

- Stroud 2011.

- Cozzens 1996, p. 547.

- Cozzens 1996, pp. 126–135.

- Cozzens 1996, pp. 350–353.

- Battles & Leaders 1987a, p. 674.

- Battles & Leaders 1987b, p. 292.

- Battles & Leaders 1987b, p. 281.

- Boatner 1959, p. 260.

- Battles & Leaders 1987b, p. 474.

- Battles & Leaders 1987b, p. 411.

- Boatner 1959, p. 68.

References

- "The Battle of Richmond, August 29–30, 1862". American Battlefield Trust. 2019.

- Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. 3. Secaucus, N.J.: Castle. 1987a [1883]. ISBN 0-89009-571-X.

- Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. 4. Secaucus, N.J.: Castle. 1987b [1883]. ISBN 0-89009-572-8.

- Boatner, Mark M. III (1959). The Civil War Dictionary. New York, N.Y.: David McKay Company Inc. ISBN 0-679-50013-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bell, Tim: Thirty-Second Texas Cavalry from the Handbook of Texas Online (November 8, 2013). Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- Cozzens, Peter (1991). No Better Place to Die: The Battle of Stones River. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-06229-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cozzens, Peter (1996). This Terrible Sound: The Battle of Chickamauga. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-06594-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shea, William L.; Hess, Earl J. (1992). Pea Ridge: Civil War Campaign in the West. Chapel Hill, N.C.: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4669-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stroud, David V.: Ector's Brigade from the Handbook of Texas Online (April 9, 2011). Retrieved September 15, 2019.