2020 Surinamese general election

Parliamentary elections were held in Suriname on 25 May 2020.[1] The elections occurred concurrently with an economic crisis in Suriname, as well as the COVID-19 crisis.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 51 seats in the National Assembly 26 seats needed for a majority | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

This lists parties that won seats. See the complete results below. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

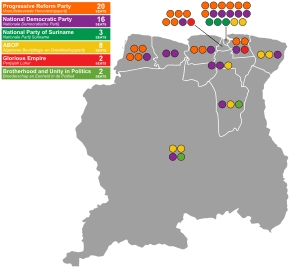

Results of the election showing seats earned by district. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Suriname |

| Constitution |

|

Government |

|

Legislature

|

|

Judiciary |

|

Elections

|

|

|

|

Electoral system

The 51 seats in the National Assembly are elected using party-list proportional representation under the D'Hondt method in ten multi-member constituencies containing between two and seventeen seats.[2] The ten electoral constituencies are coterminous with the ten administrative districts of Suriname. Voters also have the option of casting a preferential vote for one of the candidates on the chosen list in order to increase their place in the list, and the candidate(s) having obtained the most preferential votes in the lists that obtained seats are declared elected. The National Assembly subsequently elects the President.

Campaign

Both the V7 and A-Combination coalitions were dissolved shortly after the prior elections. Electoral alliances (which may have allowed residual votes of the combined parties to obtain an extra seat) were banned in 2019.[3] The Amazon Party and Party for Law and Development decided to cooperate for the elections,[4] with Amazon Party candidates appearing on the list of the Party of Law and Development.[5] The pair of ABOP and Pertjajah Luhur, as well as the pair of BEP and HVB, also decided to cooperate, opening their lists in certain regions to the other if one lacked a viable presence there.[6]

As a new parliament elects the president of the country after it sits, incumbent President Dési Bouterse (who had been ruling since 2010) and his NDP were hoping to pull off an election win in order to re-elect him for a third term, thereby retaining his national immunity from arrest for homicide charges he was convicted of by a Surinamese military court in 2019 regarding his involvement in the December murders.[7] Europol also had an active warrant out for his arrest since 16 July 1999 for cocaine trafficking,[8] although Suriname does not extradite its own citizens. According to WikiLeaks cables released in 2011, Bouterse was active in the drug trade until 2006.[9]

Economy

The second Bouterse cabinet was inaugurated in 2015 amid a recession that would peak the following year.[10] The country's debt would end up nearly doubling between 2015 and 2019,[11] partially because of economic woes as well as increased government spending and hiring of new government employees, which then made up 53% of the country's workforce (with an average wage of under USD$350 per month).[12] A poll among the readers on the website of Dagblad Suriname, a popular newspaper, showed that about two weeks before the elections, around 90% were concerned about the debts that Suriname had to pay off.[13]

In January 2020, it was announced that the equivalent of around USD$100 million had disappeared from the Central Bank of Suriname (CBvS).[14] Robert-Gray van Trikt, the Governor of the Central Bank, was remanded in custody on suspicion of conflicts of interest and falsification of loan dates.[15] In April, the Public Prosecutor's Office filed a request with the National Assembly to indict Minister of Finance Gillmore Hoefdraad with the aim of prosecuting him.[16]

The Inter-American Development Bank also forecast a 5.6% decline in the economy due to COVID-19,[17] and during the same time, prices for oil (a well of which was recently discovered off the country's coast) sharply fell, causing a loss of interest from investors. The government also passed a law on 22 March temporarily blocking foreign exchange transactions as a result of the value of the Surinamese dollar falling. On 1 April, Standard & Poor's downgraded the country's credit rating from B to CCC.[12]

COVID-19

The elections took place during the COVID-19 pandemic. Suriname's first case was diagnosed on 13 March,[18] and the country closed its borders completely the following day.[19] A curfew from 8pm to 6am was implemented over the following weeks.[12]

Conduct

The vote still had not been officially certified four days after the election. Four opposition parties alleged that this was because the ruling National Democratic Party was attempting to tamper with the results. On 28 May Ronnie Brunswijk of the opposition General Liberation and Development Party stated that NDP-affiliated people, including Dési Bouterse's grandson, came to the building where votes were being counted and attempted to steal boxes of votes and start fires.[20]

On 28 May the Onafhankelijk Kiesbureau (Independent Electoral Office) announced that it would take at least two weeks before the electoral results were declared final.[21] After four new cases of COVID-19 were identified, the process of counting the votes was halted.[22]

Results

The final results were released on 16 June, with no change in seat allocation from the preliminary figures. Candidates subsequently had two weeks to either raise objections, or approve the results.[23] On 19 June, the Independent Electoral Office declared the results binding, but the results of Tammenga and Pontbuiten would re-examined, and the results published within three weeks.[24] On 3 July, the results from Tammenga and Pontbuiten were declared binding. There were only minor changes in the counts, and no significant shifts.[25]

The VHP had its best election result since 1973, more than doubling its previous number of seats and becoming the largest party in the National Assembly. President Dési Bouterse's NDP lost more than a third of its seats, which was partly attributed to the country's economic problems and the criminal charges brought against him. ABOP had its best result since its foundation in 1990, winning eight seats, while the PL had its worst result since its establishment, winning only two seats, with one of them being an ABOP member acting as lijstduwer in Wanica.

| ||||||

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progressive Reform Party | VHP | 108,378 | 39.45 | 20 | +11 | |

| National Democratic Party | NDP | 65,862 | 23.97 | 16 | –10 | |

| National Party of Suriname | NPS | 32,394 | 11.79 | 3 | +1 | |

| General Liberation and Development Party | ABOP | 24,956 | 9.08 | 8[lower-alpha 1] | +3 | |

| Pertjajah Luhur | PL | 16,623 | 6.05 | 2[lower-alpha 1] | –3 | |

| Reform and Renewal Movement | HVB | 7,423 | 2.70 | 0 | New | |

| Brotherhood and Unity in Politics | BEP | 6,835 | 2.49 | 2 | 0 | |

| Alternative 2020 | A20 | 4,501 | 1.64 | 0 | New | |

| Party for Democracy and Development through Unity | DOE | 2,375 | 0.86 | 0 | –1 | |

| Party for Law and Development–Amazon Party | PRO/APS | 1,593 | 0.58 | 0 | 0 | |

| Surinamese Labour Party | SPA | 922 | 0.34 | 0 | 0 | |

| Progressive Workers' and Farmers' Union | PALU | 820 | 0.30 | 0 | –1 | |

| STREI! | STREI | 700 | 0.25 | 0 | New | |

| Democratic Alternative '91 | DA'91 | 659 | 0.25 | 0 | 0 | |

| People's Party for Renewal and Democracy | VVD | 349 | 0.13 | 0 | 0 | |

| Social Democratic Union | SDU | 254 | 0.09 | 0 | New | |

| The New Wind | DNW | 70 | 0.03 | 0 | New | |

| Invalid/blank votes | – | – | – | |||

| Total | 274,714 | 100 | 51 | 0 | ||

| Registered voters/turnout | 383,333 | – | – | |||

| Source: Centraal Hoofdstembureau[26][27][28] | ||||||

Seats by district

| District | ABOP | BEP | NDP | NPS | PL | VHP | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brokopondo | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Commewijne | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | |||

| Coronie | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Marowijne | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| Nickerie | 1 | 4 | 5 | ||||

| Para | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Paramaribo | 2 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 17 | ||

| Saramacca | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Sipaliwini | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |||

| Wanica | [lower-alpha 1] | 1 | 1[lower-alpha 1] | 5 | 7 | ||

| Total | 8 | 2 | 16 | 3 | 2 | 20 | 51 |

Party votes by district

| District | A20 | ABOP | BEP | DA'91 | DNW | DOE | HVB | NDP | NPS | PALU | PL | PRO/APS | SDU | SPA | STREI! | VHP | VVD | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brokopondo | 25 | 1,793 | 1,223 | 1,797 | 357 | 32 | 97 | 5,324 | ||||||||||

| Commewijne | 222 | 45 | 66 | 980 | 4,471 | 1,043 | 3,673 | 31 | 84 | 8,226 | 18,841 | |||||||

| Coronie | 7 | 88 | 919 | 389 | 147 | 19 | 51 | 1,620 | ||||||||||

| Marowijne | 100 | 5,476 | 351 | 128 | 1,983 | 111 | 45 | 14 | 356 | 13 | 8,577 | |||||||

| Nickerie | 131 | 70 | 952 | 4,532 | 775 | 1,482 | 30 | 11,783 | 19,755 | |||||||||

| Para | 372 | 2,148 | 296 | 16 | 39 | 606 | 5,114 | 1,870 | 393 | 85 | 1,693 | 30 | 12,662 | |||||

| Paramaribo | 2,559 | 11,644 | 1,872 | 414 | 56 | 1,657 | 2,571 | 29,495 | 21,654 | 429 | 2,616 | 749 | 111 | 363 | 470 | 38,780 | 226 | 115,666 |

| Saramacca | 109 | 625 | 3,044 | 703 | 439 | 17 | 5,775 | 10,712 | ||||||||||

| Sipaliwini | 42 | 3,807 | 1,876 | 16 | 171 | 3,024 | 900 | 87 | 35 | 152 | 503 | 10,613 | ||||||

| Wanica | 934 | 1,217 | 114 | 14 | 597 | 1,390 | 11,483 | 4,592 | 244 | 8,413 | 300 | 108 | 198 | 146 | 41,114 | 80 | 70,944 | |

| Total | 4,501 | 24,956 | 6,835 | 659 | 70 | 2,375 | 7,423 | 65,862 | 32,394 | 820 | 16,623 | 1,593 | 254 | 922 | 700 | 108,378 | 349 | 274,714 |

Aftermath

On 28 May, it was announced that VHP and ABOP had started negotiations for a coalition government, and that it was likely that the NPS would be included.[29] The PL also expressed interest. The coalition of the four parties would have 33 seats (a majority) in the National Assembly. However, the election of the country's President requires a two-thirds supermajority in the Assembly, meaning the coalition would either need one other legislator from the NDP or BEP to cooperate in order to elect the coalition's choice, or would need to put forward a nominee acceptable to at least one of the other two parties. If a presidential election fails to elect a candidate, a joint meeting of the Assembly, districts and the resorts (De Verenigde Volksvergadering) is held, with a winner elected by a majority vote.[30]

On 30 May it was announced that a coalition had been formed consisting of VHP, ABOP, NPS and PL. VHP leader Chan Santokhi announced his candidacy for President of Suriname, and ABOP leader Ronnie Brunswijk was announced as the coalition's candidate for Chairman of the National Assembly.[31] Other positions allocated under the agreement include Vice-Chairman of the National Assembly and governor of the Central Bank of Suriname for the VHP, Minister of Home Affairs and Minister of Social Affairs for PL, and Minister of Education and Minister of Oil and Gas Affairs for the NPS. ABOP was given the nomination for Vice President, as well as the Minister of Justice and Police, Minister of Trade, Industry & Tourism and Minister of Natural Resources and Regional Development. The remaining ministerial posts were to be held by the VHP.

On 29 June the National Assembly sat for its first session during which Ronnie Brunswijk was elected Chairman of the National Assembly unopposed. Dew Sharman became Vice Chairman.[32] On 1 July Paul Somohardjo, Chairman of Pertjajah Luhur and coalition partner of the new government, was diagnosed with COVID-19.[33] Testing revealed that NPS chairman Gregory Rusland and ABOP chairman Ronnie Brunswijk were also COVID-19 positive.[34] On 3 July Dew Sharman, Vice Chairman of the National Assembly, announced that the presidential elections would be postponed until 10 July at the earliest,[35] with the vote later set for 13 July.[36] Potential candidates were required to announce their candidacy on 7 and 8 July.[37]

On 7 July the coalition nominated Chan Santokhi for the presidency and Ronnie Brunswijk as vice president. The nominations were supported by all 33 coalition MPs.[38] As no other candidates were nominated by the deadline on 8 July,[39][40] Santokhi and Brunswijk were elected on 13 July by acclamation in an uncontested election.[41] They were inaugurated on 16 July on the Onafhankelijkheidsplein in Paramaribo in ceremony without public due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[42]

Notes

- ABOP member Miquella Soemar-Huur was elected as lijstduwer on PL's list in Wanica, and is included in PL's seat total.

References

- Convicted Suriname president says will seek re-election France24, 3 December 2019

- Electoral system IPU

- "Eerlijke verkiezingen in Suriname?". Suriname Herald (in Dutch). Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "PRO en APS leggen basis voor samenwerken". Star Nieuws (in Dutch). Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "PRO stelt kandidatenlijst open voor APS". De Ware Tijd (in Dutch). 24 March 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Hoever, Naomi (4 April 2020). "Partijen gaan lijstverbinding aan op weg naar kandidaatstelling" (in Dutch). De Ware Tijd. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Kuipers, Ank (29 November 2019). "Suriname President Bouterse convicted of murder for 1982 executions". Reuters. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- "NOVA – detail – Nieuws – Hoge raad bevestigt veroordeling bouterse". novatv.nl. Archived from the original on 2013-10-05. Retrieved 2012-06-09.

- "DESI BOUTERSE AND SHAHEED ROGER KHAN ACTIVITIES (C-AL6-00586)". 23 June 2006 – via WikiLeaks.

- "Suriname". CIA World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 2019. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- "Schuldenlast Suriname in vier jaar bijna verdubbeld". StarNieuws (in Dutch). 16 April 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Helgouach, Jocelyne; Franck, Fernandes (9 April 2020). "Surinam and the Covid-19 epidemic, a question mark horizon". FranceInfo (in French). France TV. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- "Peiling: Maakt u zich zorgen over de vele schulden die Suriname zal moeten aflossen?". Dagblad Suriname (in Dutch). 13 May 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- "US$ 100 miljoen aan kasreserve gebruikt; SBV misleid". StarNieuws (in Dutch). 30 January 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- "Surinamers betogen tegen president Bouterse om financiële chaos". Het Parool (in Dutch). 17 February 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- "Openbaar Ministerie Vraagt DNA om Hoefdraad in Staat Van Beschuldiging te Stellen". UnitedNews (in Dutch). 23 April 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- "IDB verwacht scherpe economische terugval Suriname" (in Dutch). De Ware Tijd. 18 April 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- "Eerste coronageval in Suriname" (in Dutch). De Ware Tijd. 13 March 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Thomas, Vishmohanie (13 March 2020). "Suriname sluit vanaf middernacht grenzen voor reizigers". Suriname Herald (in Dutch). Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Van Der Mee, Tonny (28 May 2020). "Oppositie Suriname: 'Kleinzoon Bouterse nam dozen uit stembureau mee'". Het Parool (in Dutch).

- Thomas, Vishmohanie. "Bindend verklaren verkiezingen pas over twee weken". Suriname Herald (in Dutch). Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- "Nieuwe covid-besmettingen leggen Suriname lam". nos.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- "Openbare zitting CHS: Geen verandering DNA-zetels". Star Nieuws (in Dutch). Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "OKB: Verkiezing DNA bindend; 2 ressorten nog niet". Star Nieuws (in Dutch). Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- "OKB verklaart uitslag Pontbuiten en Tammenga bindend". Star Nieuws (in Dutch). Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "Openbare zitting CHS: Geen verandering DNA-zetels". StarNieuws (in Dutch). 16 June 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- Uitslag verkiezingen 25 mei 2020

- CENTRAAL HOOFDSTEMBUREAU

- "Onderhandelingen nieuwe coalitie begonnen". De Ware Tijd (in Dutch). Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- "De Verenigde Volksvergadering". National Assembly (in Dutch). Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- "Breaking: Santokhi president en Brunswijk DNA-voorzitter". Star Nieuws (in Dutch). Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "Live blog: Verkiezing parlementsvoorzitter". De Ware Tijd (in Dutch). Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- "Breaking: Paul Somohardjo besmet met COVID-19". Suriname Herald (in Dutch). Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "Brunswijk ook positief; DNA-vergadering uitgesteld". Star Nieuws (in Dutch). Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "Presidentsverkiezing niet eerder dan 10 juli". De Ware Tijd (in Dutch). Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "Verkiezing president en vicepresident op 13 juli". Dagblad Suriname (in Dutch). Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- "Indiening kandidaten president en vp 7 en 8 juli". Star Nieuws (in Dutch). Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- "Santokhi en Brunswijk kandidaat president en vicepresident". De Ware Tijd (in Dutch). Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- "Kandidaatstelling Santokhi en Brunswijk een feit". Star Nieuws (in Dutch). Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- "Breaking: NDP dient geen lijst in". Dagblad Suriname (in Dutch). Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- "Live blog: Verkiezing president en vicepresident Suriname". De Ware Tijd (in Dutch). Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- "Inauguratie nieuwe president van Suriname op Onafhankelijkheidsplein". Waterkant (in Dutch). Retrieved 13 July 2020.

External links

- Official Election Site (in Dutch)

- Consulytic - Elections Suriname (in Dutch with statistics)