2012 Carterton hot air balloon crash

On 7 January 2012, a scenic hot air balloon flight from Carterton, New Zealand, collided with a high-voltage power line while attempting to land, causing it to catch fire, disintegrate and crash just north of the town, killing all eleven people on board.[1][2]

.jpg) ZK-XXF, the balloon that crashed | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 7 January 2012 |

| Summary | Collided with power lines due to pilot error and intoxication |

| Site | Clareville, near Carterton, New Zealand 41.01790°S 175.54505°E |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Cameron A-210 |

| Aircraft name | Mr Big |

| Operator | Early Morning Balloons |

| Registration | ZK-XXF |

| Flight origin | Carterton, New Zealand |

| Destination | Carterton, New Zealand |

| Occupants | 11 |

| Passengers | 10 |

| Crew | 1 |

| Fatalities | 11 |

| Survivors | 0 |

An inquiry into the accident by the Transport Accident Investigation Commission (TAIC) concluded that the balloon pilot made an error of judgement when contact with the power lines became imminent, trying to out-climb the power lines rather than using the rapid descent system to drop the balloon quickly to the ground below. Toxicology analysis of the balloon pilot, Lance Hopping, after the accident tested positive for tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), suggesting he may have been under the influence of cannabis at the time of the crash, which ultimately led to the error in judgement. The crash was the sixth transport accident in ten years the TAIC had investigated which involved key people testing positive for drugs or alcohol, and the commission has called for the government to enact stricter measures in regards to drug and alcohol use in the aviation, marine and rail industries.[3][4]

The crash is the deadliest ballooning disaster ever occurred in New Zealand. It was also the deadliest air disaster to occur in mainland New Zealand since the 1963 crash of New Zealand National Airways Corporation Flight 441, and the deadliest crash involving a New Zealand aircraft since 1979 crash of Air New Zealand Flight 901 into Mount Erebus.[nb 1][1][5]

Background

The balloon was a Cameron A-210 model, registered ZK-XXF and named Mr Big.[6] The envelope was manufactured in the United Kingdom in 1997, and was initially used in the United Kingdom before being purchased and imported into New Zealand by Early Morning Balloons Ltd in 2001. The basket and burner system, capable of carrying ten passengers plus pilot, were manufactured in 1989 and were previously used with a Thunder and Colt 160A envelope before the envelope was retired at the end of its useful life.[7]

The balloon took off at 6:38 am from its launching area in Carterton, a town of 4100 people in north-eastern Wellington Region, on a 45-minute scenic flight over the Carterton area, carrying ten passengers.[8][9] The Masterton-based pilot was one of New Zealand's most experienced balloon pilots, with more than 10,000 hours flying time, and was the safety officer for the "Balloons over Wairarapa" hot air balloon festival, held annually in March around the Carterton and Masterton area.[10] The ten passengers were all from the greater Wellington Region: two husband-and-wife couples from Masterton and Wellington, a couple from Lower Hutt, a boyfriend and girlfriend from Wellington, and two cousins from Masterton and Paraparaumu.[11] At the time, the weather was clear, with sufficient light and little wind.[1] Data collected from weather stations at six nearby vineyards confirmed that the wind was mostly calm with occasional gusts up to 11.4 kilometres per hour (7.1 mph) from the north-east.[12]

Crash

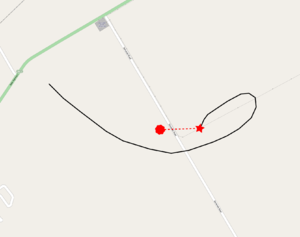

The accident occurred around 7:20 am, when the balloon was attempting to land after completing a partial figure-8 flight pattern over the Carterton area. The pilot had indicated to the chase team he was likely to land near Somerset Road, a rural through road just north of Carterton in the locality of Clareville. At first the balloon was heading north-east over Somerset Road, around 700 metres east of the road's intersection with State Highway 2. Around 400 metres north of Somerset Road, the balloon reversed direction and headed back towards the road. The two chase vehicles, carrying some of the family members of the passengers, positioned on the road ready to assist with the landing.[13]

Eyewitnesses saw the balloon climb and drift east towards a ten-metre high 33,000-volt power line running perpendicular to the road,[14][15] one of the two lines that connected the Clareville zone substation, which supplied Carterton and the surrounding rural area, to the national grid at Transpower's Masterton substation.[16] The pilot was heard shouting "duck down" as the balloon came in contact with the power line around 85 metres from the road. One of the conductor wires was caught over the top of the pilot's end of the basket, and the pilot attempted to get the balloon to climb, but the tension of the wire prevented it rising and instead the balloon slid along the conductor. Around 20 seconds later, electrical arcing occurred as the balloon caused a phase-to-phase short circuit, tripping the line and causing the 3800 properties supplied by the Clareville zone substation to lose power.[1][9][17] The arcing caused one of the four liquefied petroleum gas bottles supplying the burners to rupture, and a fire subsequently started.[18]

Two of the passengers jumped from the balloon to avoid the fire, falling ten metres to their deaths below. As the fire intensified, it caused the air inside the balloon to heat and force it to rise. Eventually, the conductor wire on the power line snapped, sending the balloon shooting upwards. The fire soon engulfed the whole balloon, and 150 metres in the air, the envelope disintegrated, causing the balloon to fall towards the ground, with the wreckage landing in a field just south of Somerset Road, around 600 metres east of the SH2 intersection.[19][20]

Emergency services were on the scene within seven minutes but, shortly after they arrived, ambulance staff found that all eleven people had died at the scene,[21] and this was later confirmed by police.[22] The bodies of the two people who jumped from the balloon were located 200 metres (700 ft) from the crash site.[23]

Aftermath

It took two days until 9 January to remove the last victims' bodies from the crash site.[24] All eleven victims' bodies were taken to Wellington Hospital to be formally identified.[23][25]

The wreckage was examined at the scene, before being packed into a shipping container and transported to the TAIC's secure workshop in Wellington.[26]

Power to the Carterton area was restored shortly after the crash using the remaining subtransmission line and spare capacity in the 11,000-volt distribution network until the damaged line was repaired. The damaged power line conductors were removed from the scene for examination.[26]

A memorial was erected in January 2016 near the site of the disaster.[27]

Investigation

The Transport Accident Investigation Commission (TAIC) opened an inquiry to investigate the cause of the accident and to recommend any safety improvements in relation to the accident.[21] The New Zealand Civil Aviation Authority was responsible for looking into any occupational health and safety and regulatory matters relating to the crash,[28] while the United Kingdom's Air Accident Investigation Branch was contacted by the TAIC in case inquiries needed to be made in relation to the Bristol-based balloon manufacturer.[29] The investigations could take up to a year to complete.[30]

On 15 February 2012, the TAIC released an urgent safety recommendation after investigators found apparent anomalies in the maintenance of the crash balloon. The recommendation to the Civil Aviation Authority recommended that they urgently check the maintenance practices and airworthiness, especially in relation to the inspection of burners, fuel systems and envelopes, and maintenance record-keeping, of the other 74 hot air balloons registered in New Zealand.[31][32]

The TAIC released its interim report on the accident on 10 May 2012. Examination of the wreckage showed electrical arcing on the basket and one of the four propane cylinders, consistent with a power line strike.[33] Details about the maintenance and record-keeping of the balloon were released. The most recent inspection had occurred on 14 September 2011, with several errors made in the records and inspection. The inspection report erroneously recorded the type certificate as B2GL, which is applicable to Cameron Balloons United States for serial numbers 5000 and higher – ZK-XXF was manufactured in the United Kingdom and was serial number 4300, so the correct type certificate was BB12. It also recorded the basket and burners as being of Cameron Balloons, not as being of Thunder and Colt. Anomalies were also identified in the maintenance logbook, including incorrect identification of the basket and burners, no record of four airworthiness directives, and no entry regarding the use of the gas bottles. The maintenance provider was also found to be using outdated versions of the Flight and Maintenance Manuals, using the 1992-released Issue 7 rather than the current Issue 10, and that the maintainers had tested the strength of the envelope by hand, rather than the prescribed method of using a spring gauge to measure actual strength.[34]

Toxicology analysis of the balloon pilot found evidence of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), indicating cannabis use.[35] The report was the second fatal aviation incident report released by the TAIC in two days in which crew members tested positive for cannabis, following on from the release of the final report into the 2010 New Zealand Fletcher FU24 crash, in which two of the skydiving instructors killed in the crash tested positive for cannabis.[36][37]

In February 2013, a report by the Civil Aviation Authority on the crash was released to The Dominion Post newspaper under the Official Information Act. The report found that the pilot's medical certificate had expired six weeks before the crash and he should have not been piloting a commercial aircraft. It also found that neither the rapid deflation system nor the parachute valve, which would have allowed for a rapid controlled descent, had been deployed despite there being sufficient time to do so, and passengers were not briefed in their emergency use.[38]

In April 2015, the findings of coroner Peter Ryan were revealed to the public.[39] In the report, he described the accident as "entirely preventable" and caused by "a significant error of judgement" by the pilot. Although there was no proof the pilot had used cannabis before the flight, statements from people who knew him, as well as post-mortem forensic tests, revealed that he was a weekly cannabis user and the long term effects of using the drug could have had an "effect on his perception and thinking".

Ryan also commented on issues with regards to safety standards in the industry, commenting on the "lack of enforcement" for mandatory drug and alcohol tests.

See also

- List of New Zealand disasters by death toll

- List of ballooning accidents

Footnotes

Notes

- Whether Air New Zealand Flight 901 occurred in New Zealand is disputed, as the crash occurred in the New Zealand-claimed Ross Dependency, which is not fully recognised by other countries.

References

- "11 dead in hot air balloon tragedy". The New Zealand Herald. 7 January 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- "Eleven dead in New Zealand hot air balloon crash". BBC News. 6 January 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- Backhouse, Matthew (31 October 2013). "Carterton balloon tragedy caused by errors of judgement". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- "New Zealand hot air balloon crash pilot 'used cannabis'". BBC News. 31 October 2013. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- Niles, Russ (6 January 2012). "New Zealand Balloon Crash Kills 11". AVweb. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- "11 dead in hot air balloon tragedy in New Zealand". News.com.au. 7 January 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- TAIC interim report, p. 19

- TAIC Final Report, para. 3.1.6

- "Multiple deaths in hot air balloon disaster". Television New Zealand. 7 January 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- "Balloon pilot 'very safety conscious'". Television New Zealand. 7 January 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- "Balloon crash – names released". New Zealand Police. 8 January 2012. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- TAIC Interim Report p.9

- TAIC Interim Report, p. 2–3

- TAIC Final Report, para. 3.2.2.

- Binning, Elizabeth; Tan, Lincoln (9 January 2011). "Instant disaster in balloon powerline strike". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- "2011 Asset Management Plan" (PDF). Powerco. pp. 52, 253. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- "Hot air balloon crash kills 11 in New Zealand; Balloon hit power lines as it fell to the ground, cutting electricity in rural area". Daily News. 6 January 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- TAIC Final Report, para 3.2.12.

- TAIC Interim Report, p.9

- Kirsty Johnston; Greer McDonald; Clio Francis; Blair Ensor; Mark Stevens (7 January 2012). "Hot air balloon crash near Carterton kills 11". Fairfax Media (via Stuff.co.nz). Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- "Developments: Hot air balloon disaster". Television New Zealand. 7 January 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- "Balloon crash investigation update". New Zealand Police. 7 January 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- "Two leapt to death from burning balloon". Sky News Australia. 7 January 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- "Final bodies removed from hot air balloon crash site". Television New Zealand. 9 January 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- "Two more balloon crash victims identified". Television New Zealand. 13 January 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- TAIC Interim Report, p.1

- Nicoll, Jared (7 January 2016). "Memorial unveiled to mark fourth anniversary of Carterton balloon tragedy". Stuff. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- "Bodies of two balloon victims returned to families". Television New Zealand. 10 January 2012. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- "Crash balloon was made in Bristol". Bristol Evening Post (via This Is Bristol). 10 January 2012. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- "Concerns over impact on ballooning tourism". Television New Zealand. 8 January 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- "Inquiry 12-001: Cameron hot air balloon, ZK-XXF, 7 January 2012 – Urgent Recommendation 001/12". Transport Accident Investigation Commission. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- "Carterton tragedy: Balloon airworthiness questioned". Fairfax Media (via Stuff.co.nz). 23 February 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- TAIC Interim Report, p. 8

- TAIC Interim Report, p. 7-8

- TAIC Interim Report p.8

- Boyer, Seamus (10 May 2012). "Balloon crash pilot had smoked cannabis – report". Fairfax Media (via stuff.co.nz). Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- Bradwell, Simon (10 May 2012). "Carterton balloon pilot had taken cannabis – investigators". Television New Zealand. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- Stewart, Matt (23 February 2013). "Balloon pilot not cleared to fly". The Dominion Post (via Stuff.co.nz). Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- "Carterton balloon deaths 'entirely preventable' – coroner". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

Further reading

- "Interim Report 12-001: Cameron Balloons A210, ZK-XXF, collision with power line and in-flight fire, Carterton, 7 January 2012". Transport Accident Investigation Commission. 10 May 2012. Archived from the original on 2 March 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- "Final Report: Aviation inquiry 12-001 Hot-air balloon collision with power lines and in-flight fire, near Carterton, 7 January 2012". Transport Accident Investigation Commission. 31 October 2013. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2013.