1999 Ivorian coup d'état

The 1999 Ivorian coup d'état took place on 24 December 1999. It was the first coup d'état since the independence of Ivory Coast and led to the President Henri Konan Bédié being deposed.

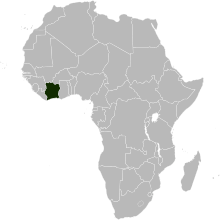

The location of Ivory Coast (green) within Africa | |

| Date | December 24, 1999 |

|---|---|

| Location | Ivory Coast |

| Type | Coup d'état |

| Cause | Corruption, political repression, and stripping immigrants from neighboring countries of their political rights |

| Target | Abidjan, Bouake, Katiola, Korhogo, and Yamoussoukro |

| Outcome | President Henri Konan Bédié being deposed |

| Arrests | Four officials of the Rally of the Republicans |

| Accused | Henri Konan Bédié |

Background

Ever since independence in 1960, Ivory Coast had been controlled by Félix Houphouët-Boigny. During the first decades of his rule, Ivory Coast enjoyed economic prosperity and was politically stable. However, the later years of his rule saw the downturn of the Ivorian economy and signs of political instability.

Henri Konan Bédié succeeded as president after Houphouët-Boigny's death in 1993. The economic situation continued to worsen. Bédié was accused of corruption, political repression, and of stripping immigrants from neighboring countries of their political rights by promoting the concept of Ivoirité, which placed in doubt the nationality of many people of foreign origin and caused tension between people from the north and the south of Ivory Coast. Dissatisfaction kept growing.

The coup

A group of soldiers led by Tuo Fozié rebelled on 23 December 1999. Refusing to step down at the soldiers' demand, Bédié was overthrown by a coup d'état the following day. Former army commander Robert Guéï, although not having led the coup d'état, was called out of retirement as head of a National Public Salvation Committee (French: Comité National de Salut Public).

Scattered gunfire were heard around Abidjan. Guéï announced the dissolution of parliament, the former government, the constitutional council and the supreme court. The rebels took control of Abidjan Airport and key bridges, set up checkpoints, and opened prison gates to release political prisoners and other inmates. Mobs took advantage of the power vacuum to hijack cars. Some parts of Abidjan were also looted by soldiers and civilians.[1]

On television, Guéï announced that he had seized power. He also made a television address to the people and foreign diplomatic personnel, in which he gave assurances that democracy would be respected, international agreements would be maintained, the security of Ivorians and non-Ivorians would be guaranteed, missions to foreign countries would be sent to explain the reasons for the coup, and the problems of farmers would be addressed.[2]

Many Ivorians welcomed the coup, saying that they hoped the army would improve Ivory Coast's shaky economic and political circumstances. France, the United States and several African countries, however, condemned the coup and called for a return to civilian rule. Canada suspended all direct aid to Ivory Coast.[3]

There were indications within a few months of the coup that the country was sliding into a pattern of arbitrariness. The Ivorian Human Rights League (French: Ligue ivoirienne des droits de l'homme) issued a condemnation of human rights abuses, charging the security forces, among other things, with summary executions of alleged criminals without investigation and of harassment of commercial entities.[4] Many cases of abuse were committed by the soldiers. Also, soldiers demanded increases in pay or bonus payments, causing many mutinies. The most serious one of these mutinies took place on 4 July 2000. The mutineers targeted the cities of Abidjan, Bouake, Katiola, Korhogo, and Yamoussoukro in particular. After some days of confusion and tension, an agreement was reached between the discontented soldiers and the authorities. Under the agreement, each soldier would receive 1 million CFA francs (about $1,400).[5][6][7]

Following the mutiny of July 2000, four officials of the Rally of the Republicans (French: Rassemblement des républicains (RDR)) were also arrested during an investigation into a possible coup attempt. The RDR is the party of Alassane Dramane Ouattara, Félix Houphouët-Boigny's last Prime Minister and the political rival of the ousted former president Henri Konan Bédié. The four arrested officials, including Amadou Gon Coulibaly, the Deputy Secretary General of the RDR, were released without charge some days later.[6]

Despite the junta's denunciation of Ivoirité, the campaign against people of foreign origin continued. In April 2000, Robert Guéï expelled the representatives of the RDR from the government. A new constitution, approved by referendum on 23 July 2000, controversially barred all presidential candidates other than those whose parents were Ivorian, and Ouattara was disqualified from the 2000 presidential election.

The tension between people from the north and the south still remained unsolved, as many people in the north are of foreign origin. Discrimination toward people originating in neighbouring countries is one of the cause of the Ivorian Civil War, which broke out in 2002.

A presidential election was held on 22 October 2000. All of the major opposition candidates except for Laurent Koudou Gbagbo of the Ivorian Popular Front (FPI) were barred from standing. Guéï was defeated by Gbagbo but refused to recognize the result. Ouattara, excluded from this election, called for a new election.[8] Street protests broke out, bringing Gbagbo to power, and Guéï fled to Gouessesso, near the Liberian border. Laurent Gbagbo took office as president on 26 October 2000.

On 13 November, Guéï recognised the legitimacy of the presidency of Gbagbo. On 10 December 2000, parliamentary elections were held and won by Gbagbo's Ivorian Popular Front. However, the election was not held in northern Ivory Coast because of the unrest related to the election boycott by the DRD until the by-election on 14 January 2001.[9][10]

See also

- Economy of Ivory Coast

- Ivorian Civil War

- Ibrahim Coulibaly, one of the rebel leaders in the 1999 coup.

References

- "Ivory coast president facing exile". BBC News. 1999-12-25. Retrieved 2011-04-02.

- "Coup leader pledges democracy". BBC News. 1999-12-24. Retrieved 2011-04-02.

- "Democracy Vow In Ivory Coast". CBS News. 1999-12-27. Retrieved 2011-04-02.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2000-04-01). "Côte d'Ivoire: Implications of the December 1999 Coup d'Etat". UNHCR. Retrieved 2011-04-02.

- "Ivory Coast 'deal' over army pay". BBC News. 2000-07-05. Retrieved 2011-04-02.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-11-22. Retrieved 2018-11-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Comparative Criminology | Africa - Cote D'Ivoire". Rohan.sdsu.edu. Archived from the original on 2010-08-31. Retrieved 2011-04-02.

- "Ivory Coast timeline". BBC News. 2011-03-31. Archived from the original on 16 April 2011. Retrieved 2011-04-02.

- "Ivory Coast: Key events". Etat.sciencespobordeaux.fr. Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2011-04-02.

- "Cote D'Ivoire 2000 Legislative Election". Cdp.binghamton.edu. Retrieved 2011-04-02.