1941 Red Army Purge

Between October 1940 and February 1942, in spite of the ongoing German attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Red Army, in particular the Soviet Air Force, as well as Soviet military-related industries were subjected to purges by Stalin.

Background

The Great Purge ended in 1939. In October 1940 the NKVD (People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs), under its new chief Lavrenty Beria, started a new purge that initially hit the People's Commissariat of Ammunition, People's Commissariat of Aviation Industry, and People's Commissariat of Armaments. High-level officials admitted guilt, typically under torture, then testified against others. Victims were arrested on fabricated charges of anti-Soviet activity, sabotage, and spying. The wave of arrests in the military-related industries continued well into 1941.

1941 Purge

In April–May 1941, a Politburo inquiry into the high accident rate in the Air Force led to the dismissal of several commanders, including the head of the Air Force, Lieutenant General Pavel Rychagov. In May, a German Junkers Ju 52 landed in Moscow, undetected by the ADF beforehand, leading to massive arrests among the Air Force leadership.[1] The NKVD soon focused attention on them and began investigating an alleged anti-Soviet conspiracy of German spies in the military, centered around the Air Force and linked to the conspiracies of 1937–1938. Suspects were transferred in early June from the custody of the Military Counterintelligence to the NKVD. Further arrests continued well after the German attack on the Soviet Union, which started on June 22, 1941.

Arrests

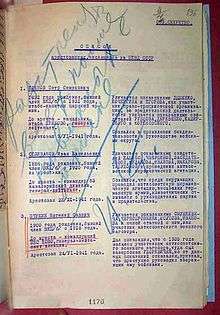

- May 30: People's Commissar of Ammunition Ivan Sergeyev and Major General Ernst Schacht

- May 31: Lieutenant General Pyotr Pumpur

- June 7: People's Commissar of Armaments Boris Vannikov and Colonel General Grigory Shtern

- June 8: Lieutenant General Yakov Smushkevich

- June 18: Lieutenant General Pavel Alekseyev

- June 19: Colonel General Alexander Loktionov

- June 24: General Kirill Meretskov and Lieutenant General Pavel Rychagov

- June 27: Lieutenant General Ivan Proskurov

In wartime

During the first months of the war, scores of commanders, most notably General Dmitry Pavlov, were made scapegoats for failures. Pavlov was arrested and executed after his forces were heavily defeated in the early days of the campaign. Only two of the accused were spared: People's Commissar of Armaments Boris Vannikov (released in July) and Deputy People's Commissar of Defense General Kirill Meretskov (released in September). The latter had admitted guilt, under torture.[2]

About 300 commanders, including Lieutenant General Nikolay Klich, Lieutenant General Robert Klyavinsh, and Major General Sergey Chernykh, were executed on October 16, 1941, during the Battle of Moscow. Others were sent to Kuybyshev, provisional capital of the Soviet Union, on October 17. On October 28 twenty individuals were summarily shot near Kuybyshev on Lavrentiy Beria's personal order, including Colonel Generals Alexander Loktionov and Grigory Shtern, Lieutenant Generals Fyodor Arzhenukhin, Ivan Proskurov, Yakov Smushkevich, and Pavel Rychagov with his wife, as well as several individuals who had been previously arrested during the immediate aftermath of the Great Purge in 1939, prior to the Red Army Purge of 1941, including politicians Filipp Goloshchyokin and Mikhail Kedrov.[2]

In November Beria successfully lobbied Stalin to simplify the procedure for carrying out death sentences issued by local military courts so that they would no longer require approval of the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court and Politburo for the first time since the end of the Great Purge. The right to issue extrajudicial death sentences was granted to the Special Council of the NKVD. With the approval of Stalin, 46 persons, including 17 generals, among them Lieutenant Generals Pyotr Pumpur, Pavel Alekseyev, Konstantin Gusev, Yevgeny Ptukhin, Nikolai Trubetskoy, Pyotr Klyonov, Ivan Selivanov, Major General Ernst Schacht, and People's Commissar of Ammunition Ivan Sergeyev, were sentenced to death by the Special Council. They were executed on the Day of the Red Army, February 23, 1942.

Aftermath

On February 4, 1942, Beria and his ally Georgy Malenkov, both members of the State Defense Committee, were assigned to supervise production of aircraft, armaments, and ammunition.

Many victims were exonerated posthumously during de-Stalinization in the 1950s–1960s. In December 1953 a special secret session of the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union, itself without due process, found Beria guilty of terrorism for the extrajudicial executions of October 1941 and other crimes, and sentenced him to death.

See also

- Case of Trotskyist Anti-Soviet Military Organization (Tukhachevsky trial)

References

- "Павел Судоплатов. Спецоперации. Лубянка и Кремль 1930-1950 годы".

- Michael Parrish. The Lesser Terror: Soviet State Security, 1939–1953. Westport, Conn: Praeger, 1996. ISBN 0-275-95113-8. P. 71–76.