1920 Louisiana hurricane

The 1920 Louisiana hurricane was a strong tropical cyclone that caused significant damage in parts of Louisiana in September 1920. The second tropical storm and hurricane of the annual hurricane season, it formed from an area of disturbed weather on September 16, 1920, northwest of Colombia. The system remained a weak tropical depression as it made landfall on Nicaragua, but later intensified to tropical storm strength as it moved across the Gulf of Honduras, prior to making a second landfall on the Yucatán Peninsula. Once in the Gulf of Mexico, the storm quickly intensified as it moved towards the north-northwest, reaching its peak intensity as a Category 2 hurricane with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h) prior to making landfall near Houma, Louisiana with no change in intensity. Afterwards, it quickly weakened over land, before dissipating on September 23 over eastern Kansas.

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

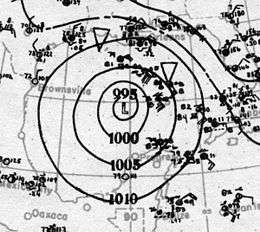

Surface weather analysis of the storm on September 21 | |

| Formed | September 16, 1920 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 23, 1920 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 100 mph (155 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 975 mbar (hPa); 28.79 inHg |

| Fatalities | 1 |

| Damage | $1.45 million (1920 USD) |

| Areas affected | Jamaica, Cuba, Louisiana and Texas |

| Part of the 1920 Atlantic hurricane season | |

As it approached the United States Gulf Coast, the hurricane forced an estimated 4,500 people to evacuate off of Galveston Island, and numerous other evacuations and precautionary measures to occur. At landfall, the hurricane generated strong winds along a wide swath of the coast, uprooting trees and causing damage to homes and other infrastructure. Heavy rainfall associated with the storm peaked at 11.9 in (300 mm) in Robertsdale, Alabama. The heavy rains also washed out railroads, leading to several rail accidents. Across the Gulf Coast, damage from the storm totaled to $1.45 million,[nb 1] and one death was associated with the hurricane.

Meteorological history

In mid-September, a trough moved across the central Caribbean Sea and into the vicinity of the Colombian islands. Becoming more organized, it developed a closed circulation on September 16,[1] and as such was classified as a tropical depression at 0600 UTC that day. For much of its early existence the depression remained weak, with winds remaining at 35 mph (55 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure below 1,005 mbar (29.7 inHg).[1] The weak disturbance later made landfall at that intensity on the Mosquito Coast near the border of Honduras and Nicaragua by 0600 UTC on September 18. The small system gained intensity as it moved over Honduras, attaining tropical storm strength on September 19 prior to entering the Gulf of Honduras near Trujillo.[1][2] In the Gulf of Honduras, the tropical storm slightly intensified to maximum sustained winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) on September 20, and later made landfall on the Yucatán Peninsula as it accelerated towards the north-northwest.[2] Despite initially being reported to have maintained intensity across the peninsula, a reanalysis of the storm determined that it had weakened to minimal tropical storm strength, before entering the Gulf of Mexico late on September 20.[1]

The weakened tropical storm began to intensify once in the Gulf of Mexico. On September 20 at 0600 UTC, the storm reached hurricane intensity as a modern-day Category 1 hurricane.[2] Continuing to intensify in the Gulf, the hurricane attained Category 2 hurricane intensity at 0000 UTC on September 22, and subsequently reached its peak intensity with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h) and an estimated minimum pressure of 975 mbar (28.8 inHg).[2] The hurricane later made landfall at peak intensity near Houma, Louisiana at 0100 UTC later that day. Maximum winds spanned 32 mi (51 km) from the center at landfall. Ships offshore the Louisiana coast also reported an eye associated with the hurricane. Once over land, the system began to quickly weaken, degenerating to tropical storm strength by 0600 UTC the same day,[2] while located near Iberville Parish.[3] Continuing to accelerate towards the north-northwest, it is estimated that the tropical cyclone dissipated on September 23 over Kansas, based on observations from nearby weather stations.[1]

Preparations and impact

Hurricane warnings were initially issued for areas of the Gulf Coast between Morgan City, Louisiana and Corpus Christi, Texas,[4] but were later moved eastward to coastal regions between Pensacola, Florida and New Orleans as the hurricane progressed closer to the coast.[5] Additional marine warnings were also issued for offshore regions that could be potentially affected by the hurricane,[4] and boats were evacuated into Gulf Coast ports.[4] Onshore, freight trains on Galveston Island were moved to the mainland in preparation for the storm.[6] Interurban railways also evacuated people out of the island,[7] with an estimated 4,500 people being evacuated.[8] The United States Coast Guard were ordered to be ready for immediate service in the event of an emergency,[9] while the US National Guard on strike duty in Galveston's Camp Hutchings were transferred to a barracks in Fort Crockett.[7][8] Oil companies abandoned operations in coastal oil fields in advance of the hurricane.[10] People along Lake Ponchartrain evacuated into New Orleans, causing hotels to overflow and forcing refugees to take shelter in other public buildings including post offices.[11]

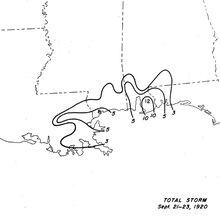

Strong winds and gusts were reported across the Gulf Coast and in the Gulf of Mexico. A ship reported a minimum central barometric pressure of 999 mbar (29.5 inHg) just prior to the storm's intensification into a hurricane.[1] Grand Isle, Louisiana reported sustained winds of 90 mph (145 km/h), and winds of at least 60 mph (95 km/h) were reported as far east as Bay St. Louis, Mississippi. As a result, numerous trees were uprooted and power lines were downed.[12] One death occurred New Orleans after being electrocuted by an electric wire that had been downed by the hurricane's strong winds.[1] The downed power lines also caused a lack of communication from areas affected, hampering relief efforts.[13] In New Orleans, at least 2,500 telephones were without service,[3] and homes were unroofed by the strong winds.[11] Along the coast and further inland, rainfall was concentrated primarily on the eastern half of the cyclone, with most rain occurring from September 21 to the 23rd. In Robertsdale, Alabama, 11.9 in (300 mm) of rain was recorded, the most associated with the hurricane.[14] A 24–hour September rainfall record was set when 1.60 in (41 mm) of rain was measured in Kelly, Louisiana.[12] However, due to the system's rapid dissipation over land, rainfall amounts remained generally less than 2 in (51 mm) in interior regions of Louisiana. In Texas, rainfall peaked at 1.20 in (30 mm) in Beaumont.[3] The heavy rains caused washouts and damage to railroads across Louisiana. A train running from Louisville, Kentucky to Nashville, Tennessee was left stranded after being washed out near Chef Menteur Pass, and other rail operations were stopped between New Orleans and Mobile, Alabama.[15] Tides of 5–6 ft (1.5–1.8 m) above average were reported in Lake Borgne and Mississippi Sound as the hurricane moved over the coast, while tides of 5.4 ft (1.6 m) above average were reported in Biloxi, Mississippi.[1] The strong storm surge caused considerable damage to Grand Isle and Manilla Village, Louisiana.[12] Due to the hurricane's landfall near low tide, however, major storm surge impacts were mitigated. Overall infrastructural damage caused by the hurricane totaled to $750,000, while crop related damage, particularly to rice and sugar cane, totaled to $700,000.[1]

Notes

- All damage totals are in 1920 United States dollars unless otherwise noted.

References

- Landsea, Chris; et al. "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- Cline, Isaac M. (September 1, 1920). "Life History of Tropical Storm in Louisiana, September 21 and 22, 1920" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 48 (9): 520–524. Bibcode:1920MWRv...48..520C. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1920)48<520:LHOTSI>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- "Great Hurricane Nears Gulf Coast; Coming Up From Yucatan Peninsula". The Washington Reporter. New Orleans, Louisiana. United Press International. September 21, 1920. p. 1. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- "Gulf People Flee Before Hurricane" (PDF). New York Times. Washington, D.C. September 21, 1920. Retrieved January 17, 2013.

- "Hurricane Nears Texas Coast". The Washington Reporter. Houston, Texas. September 21, 1920. pp. 1, 10. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- "Ready to Move Inhabitants". The Washington Reporter. Galveston, Texas. September 21, 1920. p. 10. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- "4,500 Move Out of Galveston" (PDF). New York Times. Galveston, Texas. September 21, 1920. Retrieved January 17, 2013.

- "Weather Bureau Acts". The Washington Reporter. Washington, D.C. September 21, 1920. p. 10. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- "To Move Residents Off Island" (PDF). New York Times. Houston, Texas. September 21, 1920. Retrieved January 17, 2013.

- "Small Damage Has Been Done by Hurricane". The Evening Independent. New Orleans, Louisiana. September 22, 1920. p. 10. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- Roth, David M; Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Louisiana Hurricane History (PDF). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- "Morgan City, in Main Path, Not Heard From". The Evening Independent. Washington, D.C. September 22, 1920. p. 1. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- Schoner, R.W.; Molansky, S. "Rainfall Associated With Hurricanes (And Other Tropical Disturbances)" (PDF). United States Weather Bureau's National Hurricane Research Project. p. 63. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- "Great Hurricane is Sweeping the Atlantic Coast". Greensburg Daily Tribune. Galveston, Texas; New Orelans, Louisiana. September 22, 1920. p. 1. Retrieved January 18, 2013.