1900 Gordon Bennett Cup

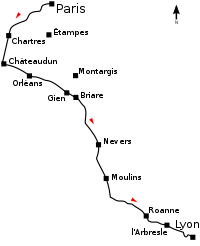

The 1900 Gordon Bennett Cup, formally titled the I Coupe Internationale, was a motor race held on 14 June 1900, on public roads between Paris and Lyon in France. It was staged to decide the inaugural holder of the Gordon Bennett Cup, which was the first prize to be awarded for motorsport on an international level. The 568.66 km (353.35 mi) route started at Paris and headed south-west as far as Châteaudun. The route then took the competitors south-easterly, passing through Orléans, Nevers, and Roanne before reaching the finish at Lyon.

| 1900 Gordon Bennett Cup | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-1906 Grand Prix seasons | |||

| Race details | |||

| Date | 14 June 1900 | ||

| Official name | I Coupe Internationale | ||

| Location | Paris to Lyon, France | ||

| Course | Public roads | ||

| Course length | 568.66 km (353.35 mi) | ||

| Podium | |||

| First |

| Panhard | |

| Second |

| Panhard | |

The race was won by Fernand Charron, who represented France and drove a car manufactured by Panhard. Léonce Girardot, also representing France on a Panhard, was the only other driver to finish. Five drivers had entered the race; three representing France, the maximum number any one country were permitted, one from Belgium, and one from the United States of America.

Background

Prior to 1900, automobile racing consisted of city-to-city races, organised by various national automobile clubs. The Gordon Bennett Cup was established by American millionaire James Gordon Bennett, Jr. with the intention of encouraging automobile industries internationally through sport. Bennett had moved to Paris in 1887 and came up with the idea of an international competition between representatives of national motoring clubs. Among the principles of the competition were that each country was limited to three entries, that the race to determine the winner of the cup would be between 550 and 650 kilometres and that the race would be held annually between 15 May and 15 August. Bennett commissioned a trophy, which he offered to the custody of the Automobile Club de France (ACF) who he also entrusted to draft the technical rules for the competition, and to arrange the inaugural event. The latter responsibility would then be bestowed on the motoring club who's representative won the previous year's race.

In April 1900, a race for motor-tricycles was held from Paris-Roubaix. It was marred by many incidents, including a collision between two competitors which left two spectators injured, one of whom was the wife of the Deputy for the Department of the Seine. Soon after, motor racing was banned within the Department of the Seine, which was then extended by the Ministry of the Interior to all of France. Any exception to the law was required to be made through the central government, who had the choice of whether to grant a permit to allow a race to go ahead.[1]

Despite rumours of building a purpose-built race track or moving the race to Italy, the race was eventually given permission to take place on public roads over the route between Paris and Lyons. However the final decision on whether the race should take place was not made until the afternoon of 12 June, less than two days before it was due to start, as the ACF had to persuade local authorities to allow the race to travel through their area.[2]

Route

The Autocar magazine had suggested that the route should take the competitors in a straight-line, so as to minimize the chance of foreign entrants getting lost.[1] The initial route proposed by the ACF in January 1900 would take the competitors from Paris to Lyon by the most direct route, heading south through Étampes, Pithiviers, and Montargis before reaching Nevers and going on to Lyon. However, this proved too short a distance to be permitted under the regulations, and a diversion was added that saw the cars initially head south-west from Paris towards Chartres and to Châteaudun. From there, they'd turn to head south-easterly towards Orléans, passing through Gien and Briare before rejoining the originally planned route at Nevers. They would then proceed towards Moulins, Roanne, and l'Arbresle before reaching the finish at Lyons.[1] The total distance to be covered was 353.35 miles (568.66 km).[3]

The late confirmation of the race taking place meant that route was, in places at least, lacking in terms of both signposting and crowd control.[1] In addition, complaints were made that no map detailing the exact route was supplied to the competitors.[4] Livestock and animals encroaching onto the road would prove to be a considerable hazard during the race.

Entries and cars

Each country was limited to a maximum of three entries for the race. The cars were required to be manufactured in their entirety in the country they represented, including the tyres. The ACF racing regulations imposed a minimum weight limit—excluding fuel, tools, upholstery, wings, lights and light fittings—of 400 kilograms (882 lb) upon each car. Each car also had to be occupied by two people at all times: a driver and a riding mechanic. In the event the combined weight of the two occupants was less than 120 kilograms (265 lb), ballast was to be added to the car to make up the difference.[5]

The ACF decided to choose its three drivers by balloting their representatives, the result of which was that Rene de Knyff, Fernand Charron, and Léonce Girardot were chosen as the three French entries for the event. Accusations of bias were made, due to de Knyff being a director of Panhard, and Charron and Giradot both being in the business of selling Panhard cars. Nevertheless, the result of the ballot stood and the three would drive a Panhard, powered by a 5.3-litre (325 cu in) four-cylinder engine producing 24 brake horsepower (18 kW). The Belgian automobile club originally indicated they would also enter the maximum complement of three cars, however in the end only Camille Jenatzy was entered for the race. His car was listed as a Snoeck-Bolide, and was effectively a French-designed Lefebvre-Bolide car built under licence in Belgium by Etablissements Mathias Snoeck, in order to meet the requirement that all parts of the car be produced in the country that it represents.[6]

Germany were also due to compete in the race; Eugen Benz was entered in a car manufactured by his father Karl Benz.[7] It was powered by a two-cylinder engine which produced 15 bhp (11 kW). However, the entry was withdrawn shortly before the start, Eugen Benz citing the short notice given of the race taking place as his reason, although he had already travelled to Paris. The final entries came from the USA, Alexander Winton and Anthony L. Riker who were to drive cars bearing Winton's name.[8] Although both arrived in Paris, only one car was designed as a racer, and Riker did not start the race.[9] Winton's car was underpowered compared to its competitors, with a one-cylinder 3.7-litre (226 cu in) engine producing 16 bhp (12 kW). Uniquely amongst the cars, the Winton featured tiller steering rather than a steering wheel.[10] The four nations were each allocated a colour, which their representatives' cars would be painted. These were blue for France, yellow for Belgium, white for Germany, and red for the USA.[9]

Race

Competitors gathered at the start line in Ville-d'Avray on the outskirts of Paris in the early hours of the morning of 14 June 1900. The race began at 3.14 am, at the drop of the starter's flag,[11] with all five cars setting off together. Over the first five miles (8 km) of the race, to Versailles, there was one minute between the leader Giradot and fifth-place Winton. Giradot continued to extend his lead, and by the time the competitors reached Limours, approximately 30 km into the race, Giradot had extended his lead to three minutes over Charron in second place, de Knyff was in third, Belgium's Jenatzy in fourth, and Winton, the American, was fifth.[12]

The next part of the race took the competitors from Chartres, through Bonneval to Châteaudun, a 44 km stretch of road that was largely straight. Unofficial timings yielded average speeds over this section, with the leader Giradot averaging 35.3 mph. Charron was the fastest, averaging 41.1 mph and Jenatzy averaged 36.7 mph. Top gear had failed on de Knyff's Panhard, and this slowed his speed down to an average of around 30 mph. However, Winton was by far the slowest of the five cars over this section, with an average speed of just 20 mph.[12]

From Châteaudun, the route headed south-easterly towards Orléans. Along this section, at Saint-Jean-de-la-Ruelle, Charron hit a gutter that ran across the road whilst travelling at speeds in excess of 50 mph, bending the back axle of his Panhard. Spectators warned the cars that followed of the hazard, by holding a green flag 30 yards in advance to give the cars time to slow down before reaching the danger.[13] Winton became the first driver to retire from the race, stopping at Orleans with a buckled wheel. The race order at Orléans, 173 km from the start, was Giradot leading by 17 minutes from Charron, with de Knyff third and a further 39 minutes behind, and Jenatzy fourth and three minutes further back.[13]

As Giradot was leaving Orléans, he swerved to avoid a horse that was in the road, and in doing so collided with a kerb stone, which damaged his Panhard's steering and broke one of the back wheels. The repairs to his back wheel took around 80 minutes, which meant that Charron assumed the race lead. de Knyff retired from the race at Glen, leaving two French cars and one Belgian car in the race.[13]

Charron and Giradot ran at a similar pace as they covered the 93 km distance between Gien and Nevers, the difference between the two over the section being just two minutes in Charron's favour. Charron gained slightly more of an advantage between Nevers and Moulins, completing the section in a time approximately four minutes faster than Giradot.[14] At Moulins, with 376 of the 569 km of the race completed, Jenatzy retired from the race, his car suffered from issues with its gears and ignition, and sustained damage after colliding with five or six dogs along the route.[15]

The gap between Charron and Giradot, now the only two drivers left in the race, stayed around an hour-and-a-half for most of the remainder of the race. 12 km from the finish in Lyons, a St. Bernard dog ran into the road in front of Charron's Panhard, which was travelling at nearly 100 km/h and the two collided. The body of the dog wedged itself between the steering gear and the springs of the Panhard, causing Charron to lose control and the car to veer off to the left.[13] It passed through two trees at the side of the road, fell into a ditch and then went through a field before rejoining the road, again narrowly avoiding more trees. Despite the excursion, the only major damage to the Panhard was that a water pump had fallen loose. Charron therefore continued with his riding mechanic, Fournier, holding the pump in place for the remaining 12 km to the finish in Lyons.[14]

Charron arrived at the finish control point, where a small crowd waited,[nb 1] at 12:23 pm, completing the race in nine hours and nine minutes, meaning he had averaged a speed of 38.6 mph. Giradot was the only other car to reach the finish, arriving at 2:00 pm having taken one hour, thirty-six minutes and twenty-three seconds longer than Charron to complete the course.[13]

Post-race

Charron's victory representing the ACF meant that France were the winners of the inaugural Gordon Bennett cup race, and the country would again host the contest the following year.

The race was not viewed as a successful event. The large gap between the only two cars to reach the end had made the finish an anticlimax. The limited number of entrants, that only two of them were from outside France and that the only two cars to finish were French also led to the race failing to make much of an impression internationally.[18] American periodical The Horseless Age wrote at the time "it is the impression (in the USA) that the race was very badly organized, that insufficient preparations had been made for it and that it must be looked upon as a failure".[15]

In a bid to address these concerns, the next two Gordon Bennett Cup races would be run in conjunction with another city-to-city event, which allowed the Gordon Bennett race to share resources with another race which didn't have limits on entry and hence had a much larger field of cars. The cup wouldn't be competed for in a standalone race again until the 1903 edition.

Classification

| Pos | Driver | Constructor | Time/Retired | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Panhard | 9:09:00 | |||||

| 2 | Panhard | 10:36:23 | |||||

| Ret | Snoeck-Bolide | Accident | |||||

| Ret | Panhard | Transmission | |||||

| Ret | Winton | Wheel | |||||

| DNS | Benz | Withdrew | |||||

| DNS | Winton | Withdrew | |||||

Source:[3] | |||||||

References

- Notes

- Footnotes

- Beaulieu (1963), p.18

- Beaulieu (1963), p.19

- Beaulieu (1963), p.201

- Beaulieu (1963), p.7

- Beaulieu (1963), p 12

- Beaulieu (1963), pp. 13-15

- Rendall (1993), p. 52

- "Another Automobile Run". The New York Times. 1900-03-25.

- Beaulieu (1963), p 16

- Beaulieu (1963), p. 15

- "La Coupe Bennett", La Petit Parisien (in French), Paris (8631), p. 3, 1900-06-15

- Beaulieu (1963), p.20

- "More about the race". The Horseless Age. 6 (14): 22. 1900-07-04.

- Beaulieu (1963), p. 21

- P. M. Heldt (1900-07-04). "The Gordon Bennett International Cup Race". The Horseless Age. 6 (14): 14.

- Smith (1980), p. 163

- Beaulieu (1963), p. 22

- "Autos Death to Dogs". Boston Evening Transcript: 24. 1900-07-14.

- Bibliography

- Douglas-Scott-Montagu, Edward John Barrington, 3rd Baron Montagu of Beaulieu (1963), The Gordon Bennett Races, London: Cassell & Company Ltd.

- Rendall, Ivan (1991), The Power and the Glory: A Century of Motor Racing, London: BBC Books, ISBN 978-0-563-36093-3

- Smith, Maurice (1980) [1979], The Car, London: Sundial Publications Ltd., ISBN 0-904230-86-4