180th Tunnelling Company

The 180th Tunnelling Company was one of the tunnelling companies of the Royal Engineers created by the British Army during World War I. The tunnelling units were occupied in offensive and defensive mining involving the placing and maintaining of mines under enemy lines, as well as other underground work such as the construction of deep dugouts for troop accommodation, the digging of subways, saps (a narrow trench dug to approach enemy trenches), cable trenches and underground chambers for signals and medical services.[1]

| 180th Tunnelling Company | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | World War I |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Royal Engineer tunnelling company |

| Role | military engineering, tunnel warfare |

| Nickname(s) | "The Moles" |

| Engagements | World War I Hohenzollern Redoubt |

Background

By January 1915 it had become evident to the BEF at the Western Front that the Germans were mining to a planned system. As the British had failed to develop suitable counter-tactics or underground listening devices before the war, field marshals French and Kitchener agreed to investigate the suitability of forming British mining units.[2] Following consultations between the Engineer-in-Chief of the BEF, Brigadier George Fowke, and the mining specialist John Norton-Griffiths, the War Office formally approved the tunnelling company scheme on 19 February 1915.[2]

Norton-Griffiths ensured that tunnelling companies numbers 170 to 177 were ready for deployment in mid-February 1915. In the spring of that year, there was constant underground fighting in the Ypres Salient at Hooge, Hill 60, Railway Wood, Sanctuary Wood, St Eloi and The Bluff which required the deployment of new drafts of tunnellers for several months after the formation of the first eight companies. The lack of suitably experienced men led to some tunnelling companies starting work later than others. The number of units available to the BEF was also restricted by the need to provide effective counter-measures to the German mining activities.[3] To make the tunnels safer and quicker to deploy, the British Army enlisted experienced coal miners, many outside their nominal recruitment policy. The first nine companies, numbers 170 to 178, were each commanded by a regular Royal Engineers officer. These companies each comprised 5 officers and 269 sappers; they were aided by additional infantrymen who were temporarily attached to the tunnellers as required, which almost doubled their numbers.[2] The success of the first tunnelling companies formed under Norton-Griffiths' command led to mining being made a separate branch of the Engineer-in-Chief's office under Major-General S.R. Rice, and the appointment of an 'Inspector of Mines' at the GHQ Saint-Omer office of the Engineer-in-Chief.[2] A second group of tunnelling companies were formed from Welsh miners from the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the Monmouthshire Regiment, who were attached to the 1st Northumberland Field Company of the Royal Engineers, which was a Territorial unit.[4] The formation of twelve new tunnelling companies, between July and October 1915, helped to bring more men into action in other parts of the Western Front.[3]

Most tunnelling companies were formed under Norton-Griffiths' leadership during 1915, and one more was added in 1916.[1][5] On 10 September 1915, the British government sent an appeal to Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand to raise tunnelling companies in the Dominions of the British Empire. On 17 September, New Zealand became the first Dominion to agree the formation of a tunnelling unit. The New Zealand Tunnelling Company arrived at Plymouth on 3 February 1916 and was deployed to the Western Front in northern France.[6] A Canadian unit was formed from men on the battlefield, plus two other companies trained in Canada and then shipped to France. Three Australian tunnelling companies were formed by March 1916, resulting in 30 tunnelling companies of the Royal Engineers being available by the summer of 1916.[1]

Unit history

180th Tunnelling Company was formed at Labuissiere in August 1915, and moved into the Vermelles sector. From its formation in until the end of the war the company served under Fourth Army.[1][5][7]

Battle of Loos

180th Tunnelling Company was engaged in constructing saps and trenches, in addition to much carrying work, during the Battle of Loos (25 September – 14 October 1915).[1]

Givenchy

180th Tunnelling Company then moved to the Givenchy area, and relieved there in early 1916 by 255th Tunnelling Company.[1]

Hohenzollern Redoubt

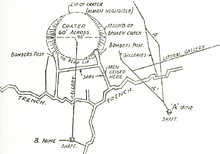

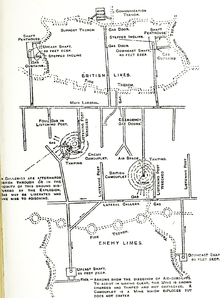

The Hohenzollern Redoubt near Loos-en-Gohelle in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region of France was the site of intense and sustained fighting between German and Allied forces. After an earlier British attack in October 1915, extensive tunnelling had been conducted by the Germans during the winter of 1915–1916; due to the nature of the clay covering and chalk below ground, mine explosions threw up high lips around mine craters, which became good observation points. It had been calculated that the German mining effort was six weeks more advanced than the British effort.[8] 170th Tunnelling Company began work for a mining attack on the Hohenzollern Redoubt on 14 December 1915. By the end of the month, it was in the process of sinking six shafts. Two sections of 180th Tunnelling Company were then attached to 170th Tunnelling Company, and the miners began another three shafts. Mining was carried out in the clay layer to distract the Germans from other mine workings in the chalk.[9]

The British tunneling effort over the winter gradually overtook the German mining operation and a plan was made to destroy the German galleries. By late February 1916, 170th Tunnelling Company had driven deep galleries through the chalk between 49–61 metres (161–200 ft) to within 9.1 metres (30 ft) of the German front-line trenches,[9] where four mines were placed underneath the shallower galleries dug by the Germans. An infantry attack was prepared by the 12th Division for 2 March.[10] The four mines would counter the German advantage in observation from Fosse 8 and possibly lead to the destruction of the German gallery system. Chamber A was loaded with 7,000 pounds (3,200 kg) of ammonal, Chamber B with 3,000 pounds (1,400 kg) of blastine and 4,000 pounds (1,800 kg) of ammonal and Chamber C with a charge of 10,550 pounds (4,790 kg).[11] 170th Tunnelling Company produced a forecast of the effect of the mines, in which mines A and B were predicted to make craters 100 feet (30 m) wide, 35 feet (11 m) deep and that Crater C to be 130 feet (40 m) wide and 35 feet (11 m) deep. The fourth, smaller mine had been planted under the side of Crater 2.[11] At 5:45 p.m., the mines were sprung, which made crater lips from which the German trenches could be seen.[12] The explosion of the four mines (the largest yet sprung by the British) on 2 March was followed up by an attack of the British infantry.[13] The new craters, A, B and C, older craters 1–5 and Triangle Crater were occupied and 170th Tunnelling Company destroyed German mine entrances found in the Triangle Crater. German counter-attacks retook Triangle Crater on 4 March and from 7–14 March skirmishing took place during heavy snowstorms and bitter cold. 170th Tunnelling Company eventually got into the German gallery system from a British tunnel and were able to demolish the system on 12 March, which relieved the threat of another German mine attack.[14][15]

On 18 March, five German mines detonated short of the British lines at 6:15 p.m., after which the Germans pushed back the British to the old front line.[16] A counter-attack was organised, and the craters re-captured. The Germans retired and drove new galleries through the clay layer on top of the chalk, which could be dug more quietly and contributed to the surprise of the German mine explosions. By the time that the crater fighting died down, both sides held the near sides of the craters.[16][17] The British exploded another mine on 19 March and the Germans two mines in the Quarries on 24 March. British mines were blown on 26 and 27 March, 5, 13, 20, 21 and 22 April; German mines were exploded on 31 March, 2, 8, 11, 12 and 23 April. Each explosion was followed by infantry attacks and consolidation of the mine lips.[18][15]

March 1918

In March 1918, the 180th Tunnelling Company acted as emergency infantry, fighting a defensive action near Ronssoy before withdrawing to Hamelet. 180th Tunnelling Company did much work in Albert during the great advance to victory, repairing all kinds of works and removing unexploded charges and mines.[1]

180th Tunnelling Company did the same in Epehy in November 1918.[1]

See also

- Mine warfare

Footnotes

- The Tunnelling Companies RE Archived 2015-05-10 at the Wayback Machine, access date 25 April 2015

- "Lieutenant Colonel Sir John Norton-Griffiths (1871–1930)". Royal Engineers Museum. Archived from the original on 15 May 2006. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- Peter Barton/Peter Doyle/Johan Vandewalle, Beneath Flanders Fields - The Tunnellers' War 1914–1918, Staplehurst (Spellmount) (978-1862272378) p. 165.

- "Corps History – Part 14: The Corps and the First World War (1914–18)". Royal Engineers Museum. Archived from the original on 3 June 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- Watson & Rinaldi, p. 49.

- Anthony Byledbal, "New Zealand Tunnelling Company: Chronology" (online Archived 2015-07-06 at the Wayback Machine), access date 5 July 2015

- Watson & Rinaldi, p. 21.

- Middleton Brumwell 2001, pp. 33–34.

- Jones 2010, p. 98.

- Edmonds 1993, pp. 174–176.

- Middleton Brumwell 2001, p. 35.

- Middleton Brumwell 2001, pp. 36–37.

- Edmonds 1993, p. 175.

- Middleton Brumwell 2001, p. 41.

- Jones 2010, pp. 97–99.

- Middleton Brumwell 2001, p. 44.

- Edmonds 1993, pp. 177, 176.

- Middleton Brumwell 2001, pp. 45–46.

References

- Edmonds, J. E. (1993) [1932]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916: Sir Douglas Haig's Command to the 1st July: Battle of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-89839-185-5.

- Jones, Simon (2010). Underground Warfare 1914–1918. Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84415-962-8.

- Middleton Brumwell, P. (2001) [1923]. Scott, A. B. (ed.). History of the 12th (Eastern) Division in the Great War, 1914–1918 (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Nisbet. ISBN 978-1-84342-228-0. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- Graham E. Watson & Richard A. Rinaldi, The Corps of Royal Engineers: Organization and Units 1889–2018, Tiger Lily Books, 2018, ISBN 978-171790180-4.

Further reading

- Alexander Barrie. War Underground – The Tunnellers of the Great War. ISBN 1-871085-00-4.

- The Work of the Royal Engineers in the European War 1914 -1919, – MILITARY MINING.

An overview of the history of 180th Tunnelling Company is also available in Robert K. Johns, Battle Beneath the Trenches: The Cornish Miners of 251 Tunnelling Company RE, Pen & Sword Military 2015 (ISBN 978-1473827004), p. 221 see online

- Arthur Stockwin (ed.), Thirty-odd Feet Below Belgium: An Affair of Letters in the Great War 1915–1916, Parapress (2005), ISBN 978-1-89859-480-2 (online).