172nd Infantry Brigade (United States)

The 172nd Infantry Brigade was a light infantry brigade of the United States Army stationed at Fort Wainwright, Alaska and later moved its headquarters to at Grafenwöhr, Germany. An active duty separate brigade, it was part of V Corps and was one of five active-duty, separate, brigade combat teams in the U.S. Army before its most recent inactivation on 31 May 2013.

| 172d Infantry Brigade | |

|---|---|

172nd Infantry Brigade CSIB | |

| Active | 5 August 1917 – 15 April 1986 17 April 1998 – 15 December 2006 17 March 2008 – 31 May 2013 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry Brigade |

| Role | Mechanized Infantry |

| Size | Brigade |

| Part of | V Corps |

| Garrison/HQ | Grafenwöhr, Germany |

| Nickname(s) | "Blackhawk Brigade" formerly Snow Hawks (Special Designation)[1] |

| Motto(s) | Caveat – "Let Him Beware" |

| Colors | Black and Bronze |

| Engagements | World War II Operation Iraqi Freedom Operation Enduring Freedom |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | COL Edward T. Bohnemann (final commander) |

| Insignia | |

| Shoulder sleeve insignia (1963-2015) |  |

First activated in 1917, the brigade was deployed to France during World War I and used to reinforce front-line units. The brigade's actions in France during that time are not completely clear. It would later be converted to a reconnaissance unit that was deployed during World War II and saw several months of combat in the European Theater. The brigade has multiple tours of duty in Operation Iraqi Freedom from 2005 until 2006 and from 2008 until 2010 and in Operation Enduring Freedom from 2011 until 2012. Its infamous 16-month deployment was one of the longest deployments for a unit serving in the OIF campaign. Most recently the brigade served a 12-month tour in Afghanistan from 2011 until 2012.

The unit has been activated and inactivated numerous times, and has also seen several redesignations. The 172nd was one of the first brigade combat teams before it was deactivated in 2006. Reactivated in 2008 from another reflagged unit, it immediately prepared for another tour of duty in Iraq. Following a series of budget cuts and force structure reductions, the unit formally inactivated on 31 May 2013 in Grafenwöhr, Germany.

Organization

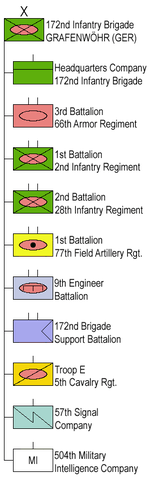

The brigade was a separate unit and did not report to a higher division-level headquarters, but instead reported directly to the V Corps of United States Army Europe. The Headquarters and Headquarters Company of the unit was located at Grafenwöhr, Germany.[2] The Unit also contained the 1st Battalion, 2d Infantry,[3] the 2nd Battalion, 28th Infantry,[4] the 1st Battalion, 77th Field Artillery,[5] the 9th Engineer Battalion,[6] the 3rd Battalion, 66th Armor,[7] and the 172nd Forward Support Battalion.[8] In addition, the brigade contained three independent companies; 504th Military Intelligence Company,[9] and Echo Troop, 5th Cavalry Regiment,[10] the 57th Signal Company.[11] All of these subordinate units were last located in Grafenwöhr.[12]

History

World War I

The 172nd Infantry Brigade (Separate), officially titled the "172d Infantry Brigade",[13] was first constituted on 5 August 1917 in the National Army as the 172nd Infantry Brigade.[13][14] It was organized on the 25th of that month at Camp Grant, in Rockford, Illinois and assigned to the 86th Infantry Division.[15] The brigade was assigned to the 86th Division and deployed to Europe for duty during World War I. It arrived in Bordeaux, France, in September 1918[13] The combat record of the unit during its World War I service is not clear, but it is known that the 86th Division was depleted when much of its force was used to reinforce other units already on the front lines.[16] Thus, the brigade received a World War I campaign streamer without an inscription, as it was not known to have fought in any engagements.[16] After a cease-fire was signed in 1918, the Brigade returned to the United States. It was demobilized in January 1919 at Camp Grant, and the camp itself was abandoned in 1921.[13][15]

On 24 June 1921 the unit was reconstituted in the Organized Reserves as Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 172nd Infantry Brigade,[13] and again assigned to the 86th Division.[15] It was organized in January 1922 at Springfield, Illinois and went through several redesignations, including Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 172nd Brigade,[13] on 23 March 1925 and Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 172nd Infantry Brigade[13] on 24 August 1936.

World War II

The Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 172nd Infantry Brigade, was converted and redesignated the 3rd Platoon, 86th Reconnaissance Troop, and assigned to the 86th Infantry Division on 31 March 1942,[13] while the Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 171st Infantry Brigade, became the remainder of the 86th Reconnaissance Troop.[13] On 15 December 1942 the troop was mobilized and reorganized at Camp Howze, in Gainesville, Texas, as the 86th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop, only to be reorganized and redesignated again on 5 August 1943 as the 86th Reconnaissance Troop, Mechanized.[13][16] For the majority of the US involvement in World War II it remained stateside, participating in the Third Army #5 Louisiana Maneuvers in 1943, among other exercises, until finally staging at Camp Myles Standish, at Boston, Massachusetts on 5 February 1945 and shipping out from Boston on 19 February 1945.[13][16]

The 86th Reconnaissance Troop arrived in France on 1 March 1945, acclimated and trained, and then moved to Köln, Germany, and participated in the relief of the 8th Infantry Division in defensive positions near Weiden which is now part of Lindenthal on 28–29 March 1945. During its few months of combat duty in Europe, the troop participated in amphibious assaults across was Danube, Bigge, Altmuhl, Isar, Inn, Mittel-Isar and Salzach rivers in Germany and Austria.[16] It was assigned to First, Third, Seventh, and Fifteenth US Armies.[16] The unit was at Salzburg on 7 May 1945 (V-E Day).[13] It was then sent back stateside to prepare for operation in the Pacific. Arriving back in New York City on 17 June 1945, the unit proceeded to Camp Gruber in Braggs, Oklahoma before staging at Camp Stoneman in Pittsburg, California on 14 August 1945.[13] The unit shipped out from San Francisco on 21 August 1945 and arrived in the Philippines on 7 September 1945, five days after the Japanese surrender.[13]

The Cold War

On 10 October 1945 the 86th Reconnaissance Troop (Mechanized) was again redesignated the 86th Mechanized Reconnaissance Troop before finally being inactivated on 30 December 1946 while still stationed in the Philippines.[13] However, the 86th Mechanized Reconnaissance Troop was reactivated again on 9 July 1952 as part of the Army Reserve.[13] It continued serving within the Army Reserve for some years. Activation of the brigade with its new structure took place on 1 July 1963 at Fort Richardson, Alaska.[17]

The Army set up an experimental Airborne unit with the designation of Company F (Airborne), 4th Battle Group, 23d Infantry in 1962 at Fort Richardson. The company commander was Captain Lawrence. When Army combat forces were reorganized from the Pentomic division battle groups to brigades with subordinate battalions, the group became the 4th Battalion, 23d Infantry and its Airborne component was Company C. The unit was used to determine how best to use Airborne soldiers in Arctic conditions throughout the vast area of Alaska.

The new structure included one Light Infantry Battalion; one Mechanized Infantry Battalion; and one Tank Company.[18] Its shoulder sleeve insignia was authorized for use on 28 August 1963[19] and its distinctive unit insignia was authorized on 8 June 1966.[19][20] The Brigade was reorganized from Mechanized Infantry to Light Infantry on 30 June 1969, with a reduction to two mechanized infantry battalions.[21] In 1974 the 172nd Infantry Brigade was reorganized again to include three light infantry battalions. [22]

US Army Alaska was known as USARAL through the 60s and 70s, whereas after the activation of the 6th Infantry Division it was known as USARAK. The two Arctic brigades, the 171st (4-9th Infantry, 1-47th Infantry [which was subsequently deactivated], and other components at Fort Wainwright) and the 172d (4-23d Infantry, 1-60th Infantry, 1-37th Artillery, 561st Combat Engineer Company, and other components at Fort Richardson) were consolidated in 1973 with the drawdown after Viet Nam. There was an administrative split between the "LIB" (Light Infantry Brigade) and the "Brigade Alaska", with the 1-43d Air Defense, 222d Aviation, 56th MP Company, 23d Construction Engineer Company, Northern Warfare Training Center- then at Fort Greely,' being assigned.

The brigade was again inactivated on 15 April 1986 at Fort Richardson, Alaska,[17] being reflagged as part of the newly reformed 6th Infantry Division.[13]

Transformation

In the late 1990s, Army leaders including General Eric Shinseki began shifting the Army force toward brigade centered operations. All separate brigades had been deactivated in the 1990s as part of the US Army's drawdown following the end of the Cold War.[23] These inactivations, along with the subsequent reorganization of US Army divisions, saw several divisional brigades stationed in bases that were far from the division's headquarters and support units. These brigades had difficulty operating without support from higher headquarters. Light infantry is a designation applied to certain types of foot soldiers (infantry) throughout history, typically having air assault and airborne qualified members with lighter equipment or armament or a more mobile or fluid function than other types of infantry, such as heavy infantry or line infantry. Historically, light infantry often fought as skirmishers, reconnaissance, hidden shock and awe attacks, basically guerilla warfare—soldiers who fight in a loose formation ahead of the main army to harass, delay and generally "soften up" an enemy before the main battle. Today, the term "light infantry" generally refers to units (including commandos and airborne units) that specifically emphasize speed and mobility over armor and firepower, to units that historically held a skirmishing role.[23]

It was Shinseki's idea to reactivate a few separate light infantry brigades and assign them their own support and sustainment units, which would allow them to function independently of division-level headquarters. These formations were termed "Brigade Combat Teams".[24] Such units could be stationed in bases far from major commands, not requiring division-level unit support, an advantage in places like Alaska and Europe, where stationing entire divisions was unnecessary or impractical. The first of the separate brigades was to be the 172d Infantry Brigade. On 17 April 1998, the U.S. Army reactivated the 172d Infantry Brigade (Separate) by reflagging the 1st Brigade, 6th Infantry Division[23] headquartered at Fort Wainwright, Alaska.[13] Two years later, the 173d Airborne Brigade was reactivated on 12 June 2000 at Caserma Ederle in Vicenza, Italy.[23] The 172d light infantry was assigned the 1st Battalion (Airborne), 501st Infantry, an airborne infantry battalion, one of only three existing outside of the 82nd Airborne Division.[25] (The other two battalions were part of the 173d Airborne Brigade based in Italy.)[25] The 172d Infantry Brigade was designed as a "Pacific theater contingency brigade." Located in Alaska, the 172d would be able to deploy to any contingencies in Alaska, Europe (over the north pole) or the Pacific.[26]

In July 2001 the US Army announced that the 172d Infantry Brigade was to become one of the Army's new Interim Brigade Combat Teams, later to be known as Stryker Brigade Combat Teams (SBCTs).[27] Changes to the brigade included the addition of some 300 Stryker vehicles, and several Unmanned Aerial Vehicles.[28] The transformation was intended to increase the brigade's mobility in operations as well as reduce its logistical footprint.[29] The project entailed around $1.2 billion in construction costs for training facilities, motor pools, and other buildings.[30] This transformation was completed when the unit was formally redesignated on 16 October 2003.[14][31] After the transformation was complete, the 172d became the third Stryker brigade in the US Army, with a force of 3,500 soldiers.[30] In 2005, the new Brigade Commander, Colonel Mike Shields, changed the motto of the infantry brigade from "Snow Hawks" to "Arctic Wolves".[14] In early 2005, the brigade was alerted that it would be deployed to Operation Iraqi Freedom for the first time. To prepare, it participated in several large exercises at the Joint Readiness Training Center at Fort Polk, Louisiana. The 220th Military Police Brigade, a reserve unit, provided additional soldiers to assist the brigade in the exercises during their final preparations for deployment.[32]

Operation Iraqi Freedom

In August 2005, the 172nd Infantry Brigade deployed to Iraq in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. The unit deployed to Mosul, Iraq. 4-14 CAV and a Stryker infantry company (A/4-23 IN and later, B/2-1 IN) were attached to 2nd Marine Expeditionary Force, and stationed at COP Rawah; away from the rest of the BDE. Duties of the unit during deployment included numerous patrol operations, searches for weapons caches, and counterinsurgency operations.[33] Its tour was to have ended on 27 July 2006, but the U.S. Army unexpectedly extended the deployment until the end of November 2006. During the extension, the unit was sent to Baghdad to quell growing sectarian violence concerns.[27] The infamous extension of the deployment had happened after some of the units of the Brigade were already touched down at their home base of Fort Wainwright, AK, forcing them to fly back to staging areas in Iraq.[14] The extension occurred after the unit's regular 12-month tour was complete, making the deployment last for a total of 16 months. As a result of the unit's action in Iraq, the brigade was awarded the Valorous Unit Award.[34]

During this action, 26 soldiers of the brigade were killed in action, and another 350 were wounded.[35] Ten additional soldiers in units attached to the brigade were killed.[36]

Inactivation 2006

Having returned from its extended tour in Baghdad, Iraq, the 172nd Stryker Brigade Combat Team was officially deactivated and the 1st Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 25th Infantry Division was activated in its place on 14 December 2006.[37]

The brigade's six battalions and four separate companies were likewise reflagged as part of the change.[38] The reflagged units were:

- 1st Battalion, 17th Infantry Regiment to 1st Battalion, 5th Infantry Regiment.[38]

- 2nd Battalion, 1st Infantry Regiment to 1st Battalion, 24th Infantry Regiment.[38]

- 4th Battalion, 23rd Infantry Regiment to 3rd Battalion, 21st Infantry Regiment.[38]

- 4th Squadron, 14th Cavalry Regiment to 5th Squadron, 1st Cavalry Regiment.[38]

- 4th Battalion, 11th Field Artillery Regiment to 2nd Battalion, 8th Field Artillery Regiment.[38]

- 172nd Brigade Support Battalion to 25th Brigade Support Battalion.[38]

- A Company, 52nd Infantry Regiment to D Company, 52nd Infantry Regiment.[38]

- 572nd Military Intelligence Company to 184th Military Intelligence Company.[38]

- 562nd Engineer Company to 73rd Engineer Company.[38]

- 21st Signal Company to 176th Signal Company.[38]

Reactivation in Germany

As part of the Grow the Army Plan announced 19 December 2007, the Army will activate and retain two Infantry Brigades in Germany until 2012 and 2013.[12] On 6 March 2008, it was announced that the 172nd Infantry Brigade would be activated as the first of these brigades, with the other being the 170th Infantry Brigade.[39] On 17 March, the 172nd Infantry Brigade was formally activated in Schweinfurt, Germany by reflagging the 1st Infantry Division's 2nd (Dagger) Brigade, which relocated to Ft. Riley, KS.[14] Colonel Jeffrey Sinclair was commanding the brigade at the time. The 172nd Infantry Brigade relocated to Grafenwöhr, Germany. The 172nd Infantry Brigade was activated with the following unit redesignations:[39]

- Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 172nd Infantry Brigade (formed from HHC, 2-1 ID)

- 2nd Battalion, 28th Infantry (reflagged from 1–26 Infantry)

- 1st Battalion, 2nd Infantry (reflagged from 1–18 Infantry)

- 3rd Battalion, 66th Armor (reflagged from 1–77 Armor)

- Troop E, 5th Cavalry (reflagged from Troop E, 4th Cavalry)

- 1st Battalion, 77th Field Artillery (reflagged from 1–7 Field Artillery)

- 172nd Support Battalion (reflagged from 299th Forward Support Battalion)

- 57th Signal Company, 9th Engineer Battalion and 504th Military Intelligence Company remain attached to 172nd but were not reflagged.

When the brigade converts to a modular design, the Brigade Special Troops Battalion will be given organic, unnumbered signal, engineer and military intelligence companies along with a chemical and military police platoons.

After its activation, the brigade began moving its components from Schweinfurt to Grafenwöhr, Germany, as part of the Grow the Army plan.[40] Simultaneously, the brigade converted to a modular structure to become a Brigade Combat Team upon completion.[41] In May 2008, the brigade was alerted that it would be returning to Iraq in the fall of that year.[42][43] The deployment was set to last 12 months,[42] and was set to start after the unit's 12-month out-of-action cycle ended on November 2008.[44][45] This would be the brigade's third tour to Iraq,[46] as it completed a tour of duty in Iraq shortly before being redesignated from the 2nd Brigade, 1st Infantry Division. The brigade began training for its deployment to the country as soon as it received orders for deployment. German military officers trained with the brigade during this preparation.[47] The soldiers of the brigade were part of a 40,000-soldier troop rotation into Iraq and Afghanistan, intended to maintain previous troop levels in both countries until late 2009.[48] In fall of 2008, the brigade completed its transition to a brigade combat team, and was redesignated as the 172nd Infantry Brigade Combat Team.[49]

In late October 2008 the brigade began moving equipment and vehicles by train from Germany in preparation for their tour in Iraq. 385 containers full of gear, as well as 75 M1A1 Abrams Tanks, M2 Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicles, and HMMWVs were sent by train on 28 October. the brigade picked up additional MRAP and uparmored HMMWVs in Kuwait.[50] The brigade deployed into theater by December 2008, replacing the 4th Brigade Combat Team, 3rd Infantry Division.[51]

A proposal was made to relocate the unit to White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico in 2012 as the 7th Brigade Combat Team, 1st Armored Division, pending discussions to leave two heavy brigades in Europe.[12]

Operation Enduring Freedom

The 172 IBCT deployed to Afghanistan in the summer of 2011. The brigade left behind its "heavy" vehicles, Bradley fighting vehicles and Abrams tanks, for MRAPs. Soldiers would spend some of their time during the deployment patrolling on foot, as their normal heavy tracked vehicles are incompatible with rugged terrain of Afghanistan. .[52] During this deployment the Brigade was responsible for Paktika province along the Pakistani border. One of the more controversial aspects of the deployment was the formation of the first US/Afghan Joint firing base with Afghan National Army Artillery firing in support of U.S. forces in the Urgun district.

Following a number of budget cuts and force structure reductions, the brigade deactivated in Germany on 31 May 2013.[53]

Honors

Unit decorations

| Ribbon | Award | Year | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Valorous Unit Award | 2006 | for service in Operation Iraqi Freedom, Permanent Order 241-05 | |

| Meritorious Unit Commendation | 2009 | Operation Iraqi Freedom, Permanent Order 351-07 | |

| Meritorious Unit Commendation | 2012 | Operation Enduring Freedom, Permanent Order 226-03 |

Campaign streamers

| Conflict | Streamer | Year(s) |

|---|---|---|

| World War I | (no inscription) | 1918 |

| World War II | Central Europe | 1944–1945 |

| Operation Iraqi Freedom | National Resolution

Iraqi Surge |

2005–2006 |

| Operation Iraqi Freedom | Iraqi Sovereignty | 2008-2009 |

| Operation Enduring Freedom | Transition I | 2011–2012 |

Notes

- "Special Unit Designations". United States Army Center of Military History. 21 April 2010. Archived from the original on 9 July 2010. Retrieved 12 July 2010.

- 172nd Infantry.army.mil Archived 13 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine, 172d Infantry Brigade Staff. Retrieved 27 June 2008.

- 1–2 Infantry Homepage Archived 18 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine, 1–2 Infantry Staff. Retrieved 27 June 2008.

- 2–28 Infantry Homepage Archived 10 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine, 2–28 Infantry Staff. Retrieved 27 June 2008.

- 1–77 Field Artillery Homepage Archived 18 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine, 1–77 Field Artillery Staff. Retrieved 27 June 2008.

- 9th Engineer Battalion Homepage Archived 15 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine, 9th Engineer Battalion Staff. Retrieved 27 June 2008

- 3–66 Armor Homepage Archived 18 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine, 3–66 Armor Staff. Retrieved 27 June 2008.

- 172nd Support Battalion Homepage, 172nd Support Battalion Staff. Retrieved 27 June 2008.

- 172D IN BDE Newsletter, 172ND IN BDE Staff. Retrieved 11 June 2009. Archived 14 June 2009.

- 172nd Infantry "Blackhawk Brigade": Blackhawk Organization Archived 18 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine. 172d Infantry Brigade Staff. Retrieved 27 June 2008.

- 57th Signal Company Homepage Archived 18 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine, 57th Signal Company Staff. Retrieved 27 June 2008.

- March 2008 Today's Focus 17 Mar 2008 Edition, Stand To! Magazine. Retrieved 27 June 2008.

- 172nd Blackhawk Brigade History Archived 18 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine, United States Army. Retrieved 7 June 2008.

- Big Red One relocating to Grafenwöhr with new name, Matt Millham, Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- Little, John G., Jr. The Official History of the 86th Division. Chicago: States Publications Society, 1921.

- 172nd Infantry Brigade (Separate) "Snow Hawks", GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- McGrath, p. 238.

- Paternostro, Anthony. "The Alaska Brigade: Arctic Intelligence and Some Strategic Considerations." Military Intelligence 6 (October–December 1980):47–50.

- US Army official page 172nd Infantry Brigade Archived 13 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine, The US Army. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- Meiners, Theodore J. "They Climb the Crags." Army Digest 22 (April 1967):36–38.

- Bender, John A. "Dynamic Training Arctic Style: A Report from Alaska." Infantry 62 (November–December 1972):36–37.

- Boatner, James G. "Rugged Training on the 'Last Frontier.' Supersoldiers of the North." Army 26 (November 1976):27–30.

- McGrath, p. xi.

- McGrath, p. xii.

- McGrath, p. 90.

- McGrath, p. 110.

- Donna Miles (28 June 2008). "172nd Stryker Brigade Legacy to Live on as Unit 'Reflags,' Gets New Commanders". American Forces Press Service. Archived from the original on 13 November 2008. Retrieved 23 November 2008.

- Preparation of an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for Force Transformation of the 172nd Infantry Brigade (Separate) and Mission Sustainment in Alaska, Federal Register Environmental Documents, US Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- Transformation EIS Archived 4 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Calvin Bagley, Colorado State University. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- A Stryking endeavour: preparation for third Stryker brigade underway in Alaska, Alaska Business Monthly. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- Pacific Army Forces Push Readiness Robert K. Ackerman, Signal Online AFCEA Magazine. Retrieved 14 August 2008.

- Military Police Support for the 172nd Stryker Brigade Combat Team Archived 10 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Robert Arnold, Jr.. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- Army.mil Featured Image Archived 1 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine, United States Army Homepage. Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- Army Prepares for Fall 2008 Active-duty Rotations in Iraq Archived 12 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine, United States Army. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- Donna Miles. "Stryker Brigade Ceremony Focuses on Accomplishments, Sacrifices". American Forces Press Service. Archived from the original on 16 June 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- Donna Miles. "'Arctic Wolves' Dedicate Wall Honoring Fallen Comrades". American Forces Press Service. Archived from the original on 16 June 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- 172nd Reflagged Archived 12 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, SRTV, United States Army. Retrieved 27 June 2008.

- 1st Brigade, 25th Infantry Division Homepage: Units Archived 4 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine. 25th Infantry Division Staff. Retrieved 27 June 2008.

- Army Announces Next Steps in USAREUR Transformation Archived 10 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine, US Army Europs Office of Public Affairs. Retrieved 27 June 2008

- Official 2BCT Message Archived 10 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine, United States Army. Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- Dagger 6 Note 03-08 Archived 18 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine, COL Jeffry Sinclair, United States Army. Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- 25,000 headed to war later this year, Michelle Tan, Army Times News. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- USAREUR unit tapped for deployment to Iraq, Seventh Army Public Affairs Office. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- Blackhawk 6 Note 08-08 Archived 10 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine, COL Jeffry Sinclair, United States Army. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- W.Pa. Guard brigade headed for Iraq Nancy A. Youssef, The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 14 August 2008.

- With Troops Strained from Multiple Extended Deployments, They Deserve a GI Bill Worthy of Their Sacrifice Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Democratic Party Caucus Senate Journal. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- Army.mil Image, United States Army Homepage. Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- 40,000 troops told of fall deployment Archived 8 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine, David Wood, Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- New commander among big changes in Europe, ArmyTimes.com. Retrieved 10 December 2008.

- Robson, Seth. 172nd Infantry Brigade ships tanks, gear for deployment, Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- "Vanguard Bde transfers authority to 172nd Infantry Bde". Multi National Corps Iraq Public Affairs Office. Archived from the original on 26 July 2009. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- Seth Robson. "Two Europe-based brigades will deploy to Afghanistan in 2011 – Europe". Stripes. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- "Final flourish as 172nd inactivates in Grafenwöhr". Retrieved 31 May 2013.

References

- McGrath, John J. (2004). The Brigade: A History: Its Organization and Employment in the US Army. Combat Studies Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-4404-4915-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 172nd Infantry Brigade (United States). |