Alpha hydroxy acid

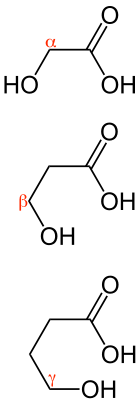

α-Hydroxy acids, or alpha hydroxy acids (AHAs), are a class of chemical compounds that consist of a carboxylic acid substituted with a hydroxyl group on the adjacent carbon. They may be naturally occurring or synthetic. AHAs are well known for their use in the cosmetics industry. They are often found in products that aid in the reduction of wrinkles, that soften strong, defining lines, and that improve the overall look and feel of the skin. They are also used as chemical peels. AHAs have effective results through continuous treatment in the cosmeceutical industry.[1][2]

Cosmetic applications

Human skin has two principal components, the avascular epidermis and the underlying vascular dermis. For any topical compound to be effective it must pass the epidermal layer and reach the live cells within the dermis.

AHAs are a group of organic carboxylic compounds. AHAs most commonly used in cosmetic applications are typically similar to those found in food products including glycolic acid (found in sugar cane), lactic acid (found in sour milk), malic acid (found in apples), citric acid (found in citrus fruits) and tartaric acid (found in grape wine) — though the source of the AHAs in cosmetics is predominantly synthetic or from bacterial or fungal fermentations. For any topical compound to be effective, including AHA, it must penetrate into the skin where it can act on living cells. Glycolic acid, having the smallest molecular size, is the AHA with greatest bioavailability and penetrates the skin most easily; this largely accounts for the popularity of this product in cosmetic applications.

Epidermal effect

AHAs have a profound effect on keratinization, which is clinically detectable by the formation of a new stratum corneum. It appears that AHAs modulate this formation through diminished cellular cohesion between corneocytes at the lowest levels of the stratum corneum.

Dermal effects

AHAs with greater bioavailability appear to have deeper dermal effects. Glycolic acid, lactic acid, and citric acid, on topical application to photodamaged skin, have been shown to produce increased amounts of mucopolysaccharides and collagen and increased skin thickness without detectable inflammation, as monitored by skin biopsies.[3]

Other applications

Organic synthesis

α-Hydroxy acids are useful building blocks in organic synthesis. For example, α-hydroxy acids are generally useful as precursors in the preparation aldehydes via oxidative cleavage.[4][5] Compounds of this class are used on the industrial-scale and include glycolic acid, lactic acid, citric acid, and mandelic acid.[6][7] They are susceptible to acid-catalyzed decarbonylation to give, in addition to carbon monoxide, a ketone/aldehyde and water.[8]

Racemic α-hydroxy acids are classically prepared by addition of hydrogen cyanide to a ketone or aldehyde, followed by acidic hydrolysis of the nitrile function of the resulting cyanohydrin product.[9]

Origins of life

α-Hydroxy acids are also prebiotic molecules[10] that could have scaffolded the origins of life.[11] These molecules, under a simple wet-drying condition can form long chains of polyesters without catalyst.[11] and form membraneless protocellular structures.[12]

Alpha hydroxy acids at different concentrations

At low concentrations (5-10%), as found in many over-the-counter products, glycolic acid (GA) reduces cell adhesion in the epidermis and promotes exfoliation. Low concentration makes possible daily application as a monotherapy or as part of a broader skin care management for such conditions as acne, photo-damage, wrinkling as well as melasma.[13][14] Care should be taken to avoid irritation to avoid the worsening of melasma or other pigmentary problems. Newer formulations combine glycolic acid with an amino acid such as arginine and time-release formulations that reduces the risk of irritation without affecting glycolic acid efficacy.[15] Supplemental use of an anti-irritant such as allantoin may also be helpful in reducing irritation.

At higher concentrations (10-50%) the effects of GA are more pronounced, but application must be limited. Such application may be used to prepare the skin for stronger glycolic acid concentrations (50 - 70%) or to prime the skin for stronger chemical applications (e.g. trichloroacetic acid).

At highest concentrations (50-70%) applied for 3 to 8 minutes under the supervision of a physician, glycolic acid promotes slitting between the cells and can be used to treat acne or photo-damaged skin (e.g. due to mottled dyspigmentation, melasma). The benefit of such short-contact application (chemical peels) depends on the pH of the solution (the more acidic the product, or the lower the pH, the more pronounced the results), the concentration of GA (higher concentrations produce more vigorous response), the length of application and prior skin conditioning such as prior use of topical vitamin A products. Although single application of 50-70% GA will produce beneficial results, multiple treatments every 2 to 4 weeks are required for optimal results. It is important to understand that glycolic acid peels are chemical peels with similar risks and side effects as other peels. Some of the side effects of AHAs chemical peeling can include hyper-pigmentation, persistent redness, scarring, as well as flare up of facial herpes infections ("cold sores").[16]

Chemical acidity

Although these compounds are related to the ordinary carboxylic acids, and therefore are weak acids, their chemical structure allows for the formation of an internal hydrogen bond between the hydrogen at the hydroxyl group and one of the oxygen atoms of the carboxylic group. Two effects emerge from this situation:

- Due to the "occupation" of electrons of the carboxylic oxygens in the hydrogen bonding, the acidic proton is held less strongly, as the same electrons are used in bonding that hydrogen too. So the pKa of 2-hydroxypropanoic acid (lactic acid) is a full unit lower compared to that of propionic acid itself (3.86[17] versus 4.87[18])

- The internal bridging hydrogen is locked in its place on the NMR timescale: in mandelic acid (2-hydroxy-2-phenylacetic acid) this proton couples to the one on carbon in the same way and magnitude as hydrogens on geminal carbon atoms.

Safety

AHAs are generally safe when used on the skin as a cosmetic agent using the recommended dosage. The most common side-effects are mild skin irritations, redness and flaking. The severity usually depends on the pH and the concentration of the acid used. Chemical peels tend to have more severe side-effects including blistering, burning and skin discoloration, although they are usually mild and go away a day or two after treatment.

The FDA has also warned consumers that care should be taken when using AHAs after an industry-sponsored study found that they can increase photosensitivity to the sun.[19] Other sources suggest that glycolic acid, in particular, may have a photoprotective effect.[20]

See also

References

- Kempers, S; Katz, HI; Wildnauer, R; Green, B (June 1998). "An evaluation of the effect of an alpha hydroxy acid-blend skin cream in the cosmetic improvement of symptoms of moderate to severe xerosis, epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, and ichthyosis". Cutis. 61 (6): 347–350. PMID 9640557.

- "Alpha Hydroxy Acids for Skin Care". Cosmetic Dermatology, Supplement: 1–6. October 1994.

- Ditre CM, Griffin TD, Murphy GF, Vasn Scott EJ: Improvement of photodamaged skin with alpha-hydroxy acid (AHA): A clinical, histological, and ultra-structural study. Dermatology 2000 Congress. Vienna, Austria. May 18–21, 1993:175.

- Ôeda, Haruomi (1934). "Oxidation of some α-hydroxy-acids with lead tetraacetate". Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan. 9 (1): 8–14. doi:10.1246/bcsj.9.8.

- Nwaukwa, Stephen; Keehn, Philip (1982). "Oxidative cleavage of α-diols, α-diones, α-hydroxy-ketones and α-hydroxy- and α-keto acids with calcium hypochlorite [Ca(OCl)2]". Tetrahedron Letters. 23 (31): 3135–3138. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)88578-0.

- Miltenberger, Karlheinz (2000). "Hydroxycarboxylic Acids, Aliphatic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a13_507. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- Ritzer, Edwin; Sundermann, Rudolf (2000). "Hydroxycarboxylic Acids, Aromatic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a13_519. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- Chandler), Norman, R. O. C. (Richard Oswald (1993). Principles of organic synthesis. Coxon, J. M. (James Morriss), 1941- (3rd. ed.). London: Blackie Academic & Professional. ISBN 978-0751401264. OCLC 27813843.

- C., Vollhardt, K. Peter (2018-01-29). Organic chemistry : structure and function. Schore, Neil Eric, 1948- (8e ed.). New York. ISBN 9781319079451. OCLC 1007924903.

- Parker, Eric T.; Cleaves, H. James; Bada, Jeffrey L.; Fernández, Facundo M. (2016-08-14). "Quantitation of α-hydroxy acids in complex prebiotic mixtures via liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry". Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 30 (18): 2043–2051. Bibcode:2016RCMS...30.2043P. doi:10.1002/rcm.7684. ISSN 0951-4198. PMID 27467333.

- Chandru, Kuhan; Guttenberg, Nicholas; Giri, Chaitanya; Hongo, Yayoi; Butch, Christopher; Mamajanov, Irena; Cleaves, H. James (2018-05-31). "Simple prebiotic synthesis of high diversity dynamic combinatorial polyester libraries". Communications Chemistry. 1 (1). doi:10.1038/s42004-018-0031-1. ISSN 2399-3669.

- Jia, Tony Z.; Chandru, Kuhan; Hongo, Yayoi; Afrin, Rehana; Usui, Tomohiro; Myojo, Kunihiro; Cleaves, H. James (22 July 2019). "Membraneless polyester microdroplets as primordial compartments at the origins of life". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences: 201902336. doi:10.1073/pnas.1902336116. PMID 31332006.

- Kalla, G; Garg, A; Kachhawa, D (2001). "Chemical peeling - Glycolic acid versus trichloroacetic acid in melasma". Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology. 67 (2): 82–4. PMID 17664715.

- Atzori, L.; Brundu, M.A.; Orru, A.; Biggio, P. (1999). "Glycolic acid peeling in the treatment of acne". European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 12 (2): 119–122. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.1999.tb01000.x.

- Ronald L. Moy; Debra Luftman; Lenore S. Kakita (2002). Glycolic Acid Peels. CRC Press. ISBN 9780824744595.

- "Chemical peel - About - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2018-02-26.

- Dawson, R. M. C. et al., Data for Biochemical Research, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1959.

- Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, CRC Press, 58th edition, page D147 (1977)

- Kurtzweil, Paula (March–April 1998). "Alpha Hydroxy Acids for Skin Care". FDA Consumer. Archived from the original on February 7, 2006. Retrieved February 5, 2006.

- PERRICONE, NICHOLAS V.; DiNARDO, JOSEPH C. (May 1996). "Photoprotective and Antiinflammatory Effects of Topical Glycolic Acid". Dermatologic Surgery. 22 (5): 435–437. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1996.tb00343.x. PMID 8634805.