Álvaro Núñez de Lara (died 1218)

Álvaro Núñez de Lara (c. 1170 – 1218) was a Castilian nobleman who played a key role, along with other members of the House of Lara, in the political and military affairs of the Kingdoms of León and Castile around the turn of the 13th century. He was made a count in 1214, served as alférez to King Alfonso VIII of Castile, was the regent during the minority of King Henry I of Castile, and was mayordomo (steward) to King Alfonso IX of León. He opposed Queen Berengaria of Castile and her son King Ferdinand III and supported the King of León during the war between the two countries of 1217–1218. At the end of his life he was a knight of the Order of Santiago, in whose Monastery of Uclés he was buried.

Family

His parents both came from powerful houses with close connections to the Leonese royalty. His father, Count Nuño Pérez de Lara, was regent during the minority of Alfonso VIII of Castile, and son of Count Pedro González de Lara, the one-time lover of Queen Urraca. His mother, Teresa Fernández de Traba, was a member of the Galician House of Traba and half-sister of King Afonso I of Portugal, their shared mother being Teresa of León, Countess of Portugal, Urraca's half-sister. When Count Nuño died in 1177, Teresa married King Ferdinand II of León, who thus became the stepfather of her children, who were then raised at court along with the future King of León, Alfonso IX.[1]

His brothers Fernando and Gonzalo were also counts and significant figures in the political and military affairs of the era. Fernando was alférez to King Alfonso VIII. Nonetheless, his outsized ambition put him at odds with the king and he had to leave Castile and seek refuge in Marrakech, where he died in 1220[2] The career of the other brother, Gonzalo, father of count Nuño González de Lara "el Bueno", played out in the Kingdom of León.

.jpg)

Early career

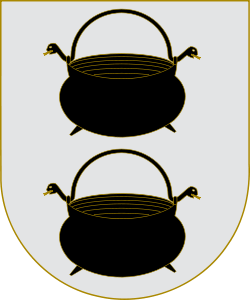

In the Abbey of Las Huelgas, near Burgos, a cream-colored cap is on display, embroidered with reddish cauldrons. It dates from the early 13th century and has been almost perfectly preserved, after having lain for centuries hermetically sealed in the stone tomb of King Henry I of Castile (reigned 1214 – 1217). But the cap was not Henry's. It is rather thought that it belonged to Álvaro Núñez de Lara, and the cauldrons may well be the oldest representation of the heraldic arms of the family [...] The presence of the cap in the young king's tomb constitutes a graphic illustration of the political domination of the House of Lara in this period, and, in a certain sense, is also a symbol of the disaster which would befall them.[3]

Upon the death of his stepfather King Ferdinand II, Álvaro established himself in the Castilian court, following his two brothers. From January 1196 he began to attest royal charters.[5] It was during this time that the Laras became close to Diego López II de Haro, Lord of Biscay, and possibly around this time Álvaro married Urraca, the daughter of Diego, whom he replaced as royal alférez in May 1199, [6][7] a post in which he served until 1201, when he handed it over to his brother Fernando, and again between 1208 and 1217. He fought alongside his brothers Fernando and Gonzalo in the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa on 16 July 1212, carrying the royal standard.[lower-alpha 1][2] The Chronica latina regum Castellae provides a vivid account of the performance of Count Álvaro in the battle.[9]

In gratitude for the valor demonstrated by the count in this battle, which marked a milestone of the Reconquista, Alfonso VIII granted him, on 31 October 1212, the village of Castroverde, referring to him as "my beloved and loyal vassal (...) as reward for the many voluntary services which you have lent me and faithfully fulfilled, and as well which you have made an effort to fulfill up to this very day; and more so as reward for the service, which is to be particularly cherished, which you performed for me on the field of battle when you carried my standard like a valiant man."[10] Years later, on 18 May 1217, Álvaro donated the village to the Order of Santiago.[lower-alpha 2]

Infante Ferdinand of León, son of Alfonso IX and his first wife Theresa of Portugal and heir to the throne of León, died in August 1214 at the age of 22.[12] Berengaria and her father King Alfonso VIII harbored the hope that Infante Ferdinand of Leon, Alfonso IX's son by his second wife, Berengaria herself, would succeed his father, although first it was necessary to arrive at an agreement with the Leonese and the Portuguese to annul the rights to the throne of the sisters of the recently deceased infante, Sancha and Dulce.[13]

However a few months later, on 6 October 1214, King Alfonso VIII of Castile died and the court decided on his son Henry to succeed him on the throne. Before dying, the king had charged the bishops, his friend Mencía López de Haro,[lower-alpha 3] and his steward, Gonzalo Rodríguez Girón, executors of his will, with the task of seeing to the carrying out of his commands and the assurance of his succession.[13] The king's widow Eleanor ceded custody of the heir to Berengaria. Weeks later, Queen Eleanor died and left the guardianship of Henry and the regency to her daughter Berengaria and the prelates of Palencia and Toledo.[13][14]

Some nobles believed that Berengaria's regency was too dependent on the support of the Bishop of Palencia, Tello Téllez de Meneses, and Rodrigo Jiménez de Rada, Archbishop of Toledo. This situation annoyed them and, according to the Chronica latina regum Castellae, "a majority of the barons decided that Álvaro ought to be regent in the king's name and take charge of the care of the realm."[15] Álvaro, according to De rebus Hispaniae, bribed García Lorenzo, a knight of Palencia and guardian of the young king, to hand Henry over to them. Berengaria conceded this reluctantly.[16][17] Given this fait accompli and with the consent of the barons and prelates of the kingdom,[18] Álvaro had to swear that neither he nor his brothers or other noblemen "... would transfer lands from or to anyone, nor would they wage war against neighboring kingdoms, nor impose tributes... under pain of conviction for high treason".[2][19] As Jiménez de Rada asserted, it was the ambition of the Laras to control the kingdom, just as Álvaro's father, Nuño Pérez de Lara, had done while regent from 1164 to 1169 during the minority of King Alfonso VIII.[20] It was during this time that Álvaro was raised to the rank of count.

Jiménez de Rada's De rebus Hispaniae is the main source for the events occurring in those years covered by the Estoria de España. The archbishop's objectivity in his recounting of events should be accepted with caution due to his sympathy for the crown, his disdain of the Laras, and his determination "to promote the interests of Toledo over those of Santiago and Seville."[21] During his years as regent, Count Álvaro fell out with the clergy and abused his position, especially in 1215 when, taking advantage of the absence of several bishops from the kingdom during the Fourth Lateran Council (1215-1216), he moved to take over their privileges and rental income and expropriated the tercias (part of the church tithes).[22] Nevertheless, on 15 February 1216, he apologized publicly and promised that we would never again collect these tercias nor suggest that they be expropriated.[23][lower-alpha 4]

In April 1216, making a show of his power, Count Álvaro signed a document in the Royal Monastery of San Benito de Sahagún in which Henry is said to reign in Toledo and Castile and "Álvaro Núñez to rule the whole country under him". He destabilized the political situation by excluding other noblemen from the center of power.[15] A notable case was that of Gonzalo Rodríguez Girón, removed in 1216 from his post as high steward which he had held for eighteen years. Other nobles, like Lope Díaz II de Haro, Lord of Biscay, Álvaro Díaz de los Cameros, Alfonso Téllez de Meneses, and the Archbishop of Toledo himself were also marginalized.[23]

In the spring of 1216, the count tried to convince King Alfonso IX to have his former wife, Queen Berengaria, hand over her castles. It may be for this reason that Berengaria decided to send her son Ferdinand to join his father in order to ensure his succession in León. Around this time, the Cortes were summoned a few times at the urging of some of the nobles. Berengaria did not attend them, either because she was not advised of them or by her own decision. Lope Díaz de Haro, Gonzalo Rodríguez Girón, Álvaro Díaz de los Cameros, Alfonso Téllez de Meneses, and Archbishop de Rada went to Berengaria, who was in the Abbey of Las Huelgas in Burgos, to ask that she intervene and respond to the abuses being committed by Álvaro.[24]

Shortly afterward, Álvaro moved to Medina del Campo with King Henry, and then to Ávila where he was knighted. He wrote to Berengaria, warning her not to act against the king's household, that is, against the court of which he was the regent.[25] Around this time, he negotiated the marriage of Henry to Mafalda, daughter of King Sancho I of Portugal, a union which was later annulled at the urging of Queen Berengaria by the bishops of Burgos and Palencia in obedience of the orders of Pope Innocent III.[26] Later, Álvaro negotiated with King Alfonso IX for the marriage of his daughter Sancha to Henry. If the marriage (which was prevented by the death of the young king) had taken place, Henry would have become the heir to the crown of León.[27][28]

In the autumn of 1216, Álvaro, claiming to act in the name of Henry I, demanded that Berengaria hand over several castles, including those of Burgos, San Esteban de Gormaz, Curiel de Duero, Valladolid, and Hita, as well as the Cantabrian ports, all of which were part of the arras paid her by Alfonso IX on the event of their marriage.[29] Berengaria sought explanations from her brother Henry, who denied being aware of such a request on the part of the regent and, alarmed by the excesses being committed by Álvaro, attempted to meet with his sister. When Álvaro learned of this, he ordered the killing of the messenger Berengaria had sent to court to determine how her brother was and to ascertain the activities of the count. Jiménez de Rada's chronicle tells that Álvaro forged a letter of Berengaria's, supposedly urging the assassination of King Henry according to the advice of the Meneses and Girón families, Tierra de Campos nobles who were openly in support of her.[30] Due to the bias shown by Jiménez de Rada and his unconditional support of Berengaria, the letter may have been authentic and not a forgery by Álvaro as the archbishop wrote.[31] Whatever the case, opposition to Álvaro grew after this episode. Rodrigo González de Valverde, a knight loyal to Berengaria, tried to organize a meeting between Berengaria and her brother Henry, but he was taken prisoner and brought to the Castle of Alarcón on Álvaro's orders.[32]

A year of great tension in Castile

According to the Chronica latina regum Castellae, the year 1217 was one of great tension, "such as never had been before in Castile". The royal high steward, Gonzalo Rodríguez Girón, was replaced by Martín Muñoz de Hinojosa. Other nobles allied with Berengaria, such as the Meneses, Girón, Haro, and Cameros families, were notably absent from royal charters. Álvaro also made changes to the chancery.[32]

The alferiz et procurator regis et regni, as he is titled in the records, succeeded in having all the castles of the kingdom handed over to him, possibly so he could install landholders and fortress captains whom he trusted. This led him into conflict with a great deal of the nobility, who noticed that he was grabbing more and more power.[33] The opposition faction included the Meneses, Girón, Haro and Cameros families, whose absence from the Royal Council is noted from February 1217. In the same month, Álvaro traveled with King Henry to Valladolid, possibly as a last-ditch effort to avoid a war. The new royal high steward, Martín Muñoz de Hinojosa, sent a letter to Berengaria seeking the surrender of the castles of Burgos and Valladolid as well as the Cantabrian ports. It seems that she handed over all of these except for Valladolid, although this did not prevent the conflict. Berengaria was staying at the castle of Autillo de Campos, which was controlled by the Girón family.[34] Álvaro refused to relinquish his power. The chronicles mention that the Girón family, García Fernández de Villamayor, Guillén Pérez de Guzmán, son-in-law of Gonzalo Rodríguez Girón, and Gil Manrique marched to Autillo to support Berengaria. Lope Díaz de Haro entrenched himself in Miranda de Ebro with some 300 knights. When Álvaro discovered this, he sent his brother Gonzalo, who set out with a larger army. The clergy succeeded in preventing a battle, and Gonzalo returned to court while Lope Díaz de Haro met up with Berengaria in Autillo.[35]

In March 1217, Álvaro, accompanied by his brothers Counts Fernando and Gonzalo, Martín Muñoz de Hinojosa, García Ordóñez, Guillermo González de Mendoza, and other nobles, invaded Tierra de Campos, where the Girón and Meneses families held inherited lands, causing much destruction in the valley of Trigueros. They then headed for the castle of Montealegre and the lands of Suero Téllez de Meneses. His relatives, Gonzalo Rodríguez Girón and Alfonso Téllez de Meneses, came to his aid with their armed retinues, although they retreated and avoided waging battle on finding out that the young King Henry was among the regent's forces. Alfonso Téllez de Meneses surrendered the castle and marched to Villalba del Alcor, pursued by Álvaro's troops, where he defended the castle during a seventy-day siege without the support of the nobles who were still in Autillo.[35] Subsequently, Álvaro's troops marched on Autillo and Cisneros and laid siege to Berengaria and her supporters. Lope Díaz de Haro and Gonzalo Rodríguez Girón headed to the court of León to ask that Infante Ferdinand come in aid of his mother. Meanwhile, King Henry lifted the siege of Autillo as Álvaro made his way to Frechilla, laying waste to Girón's lands.[36] Berengaria found herself forced to sue for peace, surrendering the places which were then in the power of King Henry and Count Álvaro. During Infante Ferdinand's absence from the court of León, Álvaro was appointed royal high steward at the end of 1217, and Sancho, son of Queen Urraca López de Haro and King Ferdinand II of León, replaced him as royal alférez.[37] Count Álvaro and the court of Castile established themselves in the episcopal palace of Palencia. The bishop at the time was Tello Téllez de Meneses, brother of Alfonso and Suero Téllez de Meneses and a relative of the Girón family.

Death of Henry I, abdication of Berengaria, and succession of Ferdinand III

In May 1217, Álvaro established himself in the episcopal palace of Palencia with the Castilian court and King Henry. [31] On 26 May, the young king suffered an accident while playing with other children in the palace courtyard when a tile which came loose from the roof fell and struck him on the head, causing a fatal injury.[19][37] This accident marked the beginning of Álvaro's downfall. He tried to conceal the king's death and brought his body to the castle of Tariego. Berengaria learned of her brother's death almost immediately, probably thanks to her spies in the Leonese court.[31] She took charge of recovering her brother's body and bringing it to the family vault in the Abbey of Las Huelgas in Burgos, where he was buried.[19]

Meanwhile, Berengaria asked her son, the future King Ferdinand III, who was with his father King Alfonso IX in Toro, to come join her.[18] She entrusted this mission to three of her most loyal supporters, Gonzalo Rodríguez Girón, Alfonso Téllez de Meneses, and Lope Díaz II de Haro. They were to convince Alfonso that Infante Ferdinand must return to join his mother, without revealing the plans for the succession to the throne of Castile, and to accompany him to Autillo, where she was, on the pretext that the castle had been attacked, and hiding the news of the death of her brother Henry.[38] Although the infantas Sancha and Dulce rejected the noblemen's explanations, they finally convinced them that Henry was safe and sound and succeeded in bringing Infante Ferdinand to join his mother in Autillo, where shortly afterward he was acclaimed king.[39]

This was done without the approval of the court and the councils of the most important towns of Castile which met in Segovia and later in Valladolid to deal with the succession issue. Some preferred the fulfillment of the terms of the Treaty of Sahagún by which Alfonso IX would be proclaimed King of Castile, thereby uniting the two crowns, or otherwise that the throne should pass to Berengaria, a choice which ultimately prevailed. Berengaria immediately abdicated in favor of her son, who was proclaimed king on 2 July 1217 in Valladolid.[40]

And they all said with one voice that the Castilians would never submit to the French nor to the Leonese, but would always have a lord and king from the lineage of the kings of Castile.[40]

War between the two kingdoms and Álvaro's defeat

Although Berengaria was the eldest of the children of Alfonso VIII of Castile, Álvaro had claimed that Blanche of Castile, queen consort of France by her marriage to Louis VIII, should succeed the recently deceased King Henry. He sent her a letter to this effect, which she rejected, and she asked that Álvaro hand over the castles he offered her to her sister Berengaria.[41] Berengaria and King Ferdinand moved immediately to Palencia. Ferdinand's troops marched to Dueñas where his partisans started negotiations to put an end to hostilities. Álvaro reproached Berengaria for the rushed coronation of Ferdinand and sought custody of him, Berengaria refused the offer, although the new king was already approaching eighteen years of age. Álvaro's claims were dismissed and King Ferdinand and his retinue marched to Valladolid.

On 4 July, two days after Ferdinand's coronation, his father, King Alfonso IX, who still had not renounced his claims to the throne of Castile, invaded the Tierra de Campos and occupied Urueña, Villagarcía, Castromonte and Arroyo.[42] Meanwhile, Infante Sancho Fernández of León who at the time was the royal alférez and tenant-in-chief of León, Salamanca, and other places, invaded Ávila, but was repelled by the town militia and forced to retreat.[42] King Ferdinand tried to arrive at an agreement with his father wherein he would renounce the Castilian throne. Alfonso IX proposed that he secure a papal dispensation in order to remarry Berengaria, recognizing her rights to the throne of Castile, and that the two kingdoms unite upon their deaths, and that they be succeeded by their son Ferdinand as the sole king.[42]

The Castilians rejected this proposal and Alfonso IX set out for Burgos to take the city. Berengaria and her supporters sent Lope Díaz II de Haro and the brothers Rodrigo and Álvaro Díaz de los Cameros to protect Dueñas, fearing an attack from Alfonso. Advised by Álvaro, Alfonso headed toward Burgos by way of Laguna de Duero, Torquemada, and Tordómar, laying waste along the way to the lands of Berengaria's high steward García Fernández de Villamayor.[43] Finally he decided to return to León after weighing the difficulty of taking Burgos. On his way through Palencia, he laid waste to the lands of his enemies, the Girón and Meneses families and advanced as far as Torremormojón. Meanwhile, troops from Ávila and Segovia arrived at the Castilian court, which was in Palencia, to support King Ferdinand, who had already recovered control of Burgos, Lerma, Lara, and Palenzuela, although Muñó remained loyal to Álvaro.[43] In the middle of August 1217, King Ferdinand entered Burgos, where he was acclaimed. There were still several fortresses left to be recovered, including Belorado, Nájera, Navarrete, and San Clemente. The first two remained loyal to Álvaro's brother Gonzalo, while the last two surrendered to the king.[44]

In September 1217, King Ferdinand left Burgos and headed toward Palencia. Álvaro's brother Fernando lay in ambush at Revilla Vallejera, but the ambush failed on being found out by the king's forces. Álvaro attempted another ambush on the outskirts of Herreruela de Castillería. On the 20th, the brothers Alfonso and Suero Téllez de Meneses along with Álvaro Rodríguez Girón, Gonzalo's brother, caught the Lara brothers by surprise. While his brothers escaped, Álvaro was taken prisoner to Valladolid where he was obliged, as a minimal condition of release, to relinquish the fortresses he controlled, including Alarcón, Cañete, Tariego, Amaya, Villafranca Montes de Oca, Cerezo de Río Tirón, Pancorbo, Belorado, and other places.[45]

Once Álvaro was back in León, where he still held the post of royal high steward, the kings of León and Castile agreed a truce in November 1217 in which Álvaro and his brother Fernando Núñez de Lara both took part.[46] However, the peace did not hold and, possibly encouraged by Álvaro, Alfonso IX invaded Castile in the spring of 1218 and took the fortress of Valdenebro near Medina de Rioseco. Álvaro tried to recover the castles he was forced to cede when he was captured and imprisoned, and offered to exchange them for Valdenebro, an offer which Ferdinand III refused. Ferdinand III went to Tordehumos whence he resisted the invasions of the Laras who, in turn, convinced Alfonso IX to break the truce and attack Castile. [46]

Alfonso's troops set out from Salamanca. His son Ferdinand decided to stage his first invasion of León, sending Lope Díaz de Haro, Álvaro Díaz de Cameros, and García Fernández de Villamayor. However, soon they were forced to retreat and seek refuge in Castrejón de la Peña, which was then surrounded by Alfonso and the Laras. Álvaro, taking part in the siege, became gravely ill and left for Toro, where he decided to join the Order of Santiago.[47]

Death and burial

.jpg)

According to the chronicle of Archbishop Jiménez de Rada, Álvaro Núñez de Lara took ill and died in Castrejón, where he had come in pursuit of Gonzalo Rodríguez Girón and Lope Díaz de Haro. The Crónica general vulgata differs from this account, stating that he was taken to Toro, joined the Order, and died there.

Marriage and children

Álvaro married Urraca Díaz de Haro, daughter of Diego López II de Haro, Lord of Biscay, and his wife Toda Pérez de Azagra. They had no children. In 1217, he gave his wife's aunt Urraca López de Haro several properties in la Bureba which allowed the queen dowager of León to found the Abbey of Santa María la Real de Vileña.

He had four illegitimate children with Teresa Gil de Osorno: [47]

- Fernando Álvarez de Lara, who inherited Valdenebro, the village after which his descendants took their name. In 1228, his distant cousin Aurembiaix of Urgel gave him an ecclesiastical property.[48] He married Teresa Rodríguez de Villalobos.[49]

- Gonzalo Álvarez de Lara.

- Rodrigo Álvarez de Lara. He distinguished himself in his military career and took part in the conquest of Cordoba and Seville. He received Tamariz and Alcalá de Guadaíra in the subsequent land distributions.[50] His signatures are found on royal charters until 1260. He married Sancha Díaz de Cifuentes, [49] daughter of Diego Froilaz and Aldonza Martínez de Silva.

- Nuño Álvarez de Lara.

Notes

- Alfonso VIII was the first to have a castle depicted on his arms, which were borne by the royal standard which Count Álvaro carried at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa.[8]

- On that date, the grand master of the order granted the count and his wife Urraca the villages of Paracuellos and Moratilla as a loan for life and, in gratitude, they donated Castroverde to the order.[11]

- Mencía was a daughter of Lope Díaz I de Haro. After being widowed of Count Álvaro Pérez de Lara, she founded the Convent of San Andrés de Arroyo of which she ultimately became the abbess.

- "Sepan todos los que vieren esta carta, que yo, el Señor Conde Álvaro Núñez, con el consejo del Maestro de Uclés, del Prior del Hospital, de D. Gonzalo Núñez, de D. Gonzalo Rodríguez, de D. Rodrigo Rodríguez, de don Ordunio Martínez y de toda la corte, prometo a Dios, a la bienaventurada María, su madre, y a la santa Iglesia, que jamás tomaré en adelante las tercias de las Iglesias para los gastos del rey, ni aconsejaré que se tomen, y no haré fuerza ni injuria para tomarlas, ni para darlas a nadie, si no es donde la ley divina ordena dar; y en todo lo posible impediré que nadie les haga injuria, mientras tuviere en mi custodia al rey D. Enrique.” See p. 175, Gorosterratzu, Javier Don Rodrigo Jiménez de Rada, gran estadista, escritor y prelado: estudio documentado de su vida

References

- Torres Sevilla-Quiñones de León 1999, p. 231.

- Torres Sevilla-Quiñones de León 1999, p. 232.

- Doubleday 2001, p. 55.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, p. 244.

- Martínez Díez 2007, p. 218.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, p. 245.

- Martínez Díez 2007, p. 224.

- Martínez Díez 2007, p. 169.

- Doubleday 2001, p. 62.

- Rivera Garretas 1995, Doc. 78, pp. 290-291.

- Martínez Díez 2007, p. 241.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, p. 249.

- Martínez Díez 2007, pp. 52–53.

- Doubleday 2001, p. 63.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, p. 250.

- Doubleday 2001, p. 65.

- Torres Sevilla-Quiñones de León 1999, p. 233.

- Martínez Díez 2007, p. 53.

- Martínez Díez 2007, pp. 24–25.

- Doubleday 2001, p. 64.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, pp. 252–253.

- Doubleday 2001, p. 66.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, p. 254.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, pp. 254–255.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, p. 255.

- Doubleday 2001, p. 68.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, p. 256.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, p. 258.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, p. 259.

- Doubleday 2001, p. 67.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, p. 260.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, pp. 262–263.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, p. 263.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, p. 264.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, p. 265.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, p. 266.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, p. 267.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, pp. 267–268.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, p. 269.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, p. 268.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, p. 270.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, p. 271.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, p. 272.

- Doubleday 2001, p. 69.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, p. 275.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, p. 276.

- Doubleday 2001, p. 76.

- Sánchez de Mora 2003, p. 277.

- Doubleday 2001, p. 77.

Bibliography

- Doubleday, Simon R. (2001). Los Lara. Nobleza y monarquía en la España medieval (in Spanish). Madrid: Turner Publications, S.L. ISBN 84-7506-650-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martínez Diez, Gonzalo (2007). Alfonso VIII, rey de Castilla y Toledo (1158-1214) (in Spanish). Gijón: Ediciones Trea, S.L. ISBN 978-84-9704-327-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Menéndez Pidal de Navascues, Faustino (1982). "Heráldica medieval española:La Casa Real de León y Castilla" (in Spanish). I. Hidalguía. Inst. Salazar y Castro (C.S.I.C.): 55. ISBN 84-00051505. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Rivera Garretas, Milagros (1995). La Encomienda, el Priorato, y la Villa de Uclés en la Edad Media (1174-1310): Formación de un señorío de la Orden de Santiago (in Spanish). Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. ISBN 84-00-05970-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sánchez de Mora, Antonio (2003). "La nobleza castellana en la plena Edad Media: el linaje de Lara. Tesis doctoral. Universidad de Sevilla" (in Spanish). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Shadis, Miriam (2009). Berenguela of Castile (1180–1246) and Political Women in the High Middle Ages. Palgrave Macmillan.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Torres Sevilla-Quiñones de León, Margarita Cecilia (1999). Linajes nobiliarios de León y Castilla: Siglos IX-XIII (in Spanish). Salamanca: Junta de Castilla y León, Consejería de educación y cultura. ISBN 84-7846-781-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)