Monarchy of the United Kingdom

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional monarchy of the United Kingdom, its dependencies (the Bailiwick of Guernsey, the Bailiwick of Jersey and the Isle of Man) and its overseas territories. The current monarch and head of state is Queen Elizabeth II, who ascended the throne in 1952.

| Queen of the United Kingdom | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) Royal coats of arms | |

| Incumbent | |

| |

| Elizabeth II since 6 February 1952 | |

| Details | |

| Style | Her Majesty |

| Heir apparent | Charles, Prince of Wales |

| Residence | See list |

| Appointer | Hereditary |

| Website | www.royal.uk |

| This article is part of a series on |

| United Kingdom politics |

|---|

.svg.png) |

|

Constitution

|

|

|

|

Executive

Elizabeth II

Boris Johnson (C)

Dominic Raab (C)

|

|

Legislature

Elizabeth II

The Lord Fowler

Sir Lindsay Hoyle

Sir Keir Starmer (L)

|

|

Judiciary Elizabeth II (Queen-on-the-Bench) Supreme Court

The Lord Reed

The Lord Hodge

|

|

Bank of England

Andrew Bailey

Monetary Policy Committee

|

|

Elections

UK General Elections

European Parliament Elections (1979–2019)

Scottish Parliament Elections

Northern Ireland Assembly Elections

Welsh Parliament (Senedd Cymru) Elections

UK Referendums

|

|

Devolution

Northern Ireland

|

|

Administration

Northern Ireland

|

|

Crown dependencies

|

|

Overseas Territories

|

|

Foreign relations

|

|

The monarch and their immediate family undertake various official, ceremonial, diplomatic and representational duties. As the monarchy is constitutional the monarch is limited to functions such as bestowing honours and appointing the prime minister, which are performed in a non-partisan manner. The monarch is also Head of the British Armed Forces. Though the ultimate executive authority over the government is still formally by and through the monarch's royal prerogative, these powers may only be used according to laws enacted in Parliament and, in practice, within the constraints of convention and precedent. The Government of the United Kingdom is known as Her (His) Majesty's Government.

The British monarchy traces its origins from the petty kingdoms of early medieval Scotland and Anglo-Saxon England, which consolidated into the kingdoms of England and Scotland by the 10th century. England was conquered by the Normans in 1066, after which Wales too gradually came under control of Anglo-Normans. The process was completed in the 13th century when the Principality of Wales became a client state of the English kingdom. Meanwhile, Magna Carta began a process of reducing the English monarch's political powers. From 1603, the English and Scottish kingdoms were ruled by a single sovereign. From 1649 to 1660, the tradition of monarchy was broken by the republican Commonwealth of England, which followed the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. The Act of Settlement 1701 excluded Roman Catholics and their spouses from succession to the English throne. In 1707, the kingdoms of England and Scotland were merged to create the Kingdom of Great Britain, and in 1801, the Kingdom of Ireland joined to create the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The British monarch was the nominal head of the vast British Empire, which covered a quarter of the world's land area at its greatest extent in 1921.

In the early 1920s the Balfour Declaration recognised the evolution of the Dominions of the Empire into separate, self-governing countries within a Commonwealth of Nations. In the years after the Second World War, the vast majority of British colonies and territories became independent, effectively bringing the Empire to an end. George VI and his successor, Elizabeth II, adopted the title Head of the Commonwealth as a symbol of the free association of its independent member states. The United Kingdom and fifteen other independent sovereign states that share the same person as their monarch are called Commonwealth realms. Although the monarch is shared, each country is sovereign and independent of the others, and the monarch has a different, specific, and official national title and style for each realm.

Constitutional role

In the uncodified Constitution of the United Kingdom, the monarch (otherwise referred to as the sovereign or "His/Her Majesty", abbreviated H.M.) is the head of state. The Queen's image is used to signify British sovereignty and government authority—her profile, for instance, appearing on currency,[1] and her portrait in government buildings.[2] The sovereign is further both mentioned in and the subject of songs, loyal toasts, and salutes. "God Save the Queen" (or, alternatively, "God Save the King") is the British national anthem.[3] Oaths of allegiance are made to the Queen and her lawful successors.[4]

The monarch takes little direct part in government. The decisions to exercise sovereign powers are delegated from the monarch, either by statute or by convention, to ministers or officers of the Crown, or other public bodies, exclusive of the monarch personally. Thus the acts of state done in the name of the Crown, such as Crown Appointments,[5] even if personally performed by the monarch, such as the Queen's Speech and the State Opening of Parliament, depend upon decisions made elsewhere:

- Legislative power is exercised by the Queen-in-Parliament, by and with the advice and consent of Parliament, the House of Lords and the House of Commons.

- Executive power is exercised by Her Majesty's Government, which comprises ministers, primarily the prime minister and the Cabinet, which is technically a committee of the Privy Council. They have the direction of the Armed Forces of the Crown, the Civil Service and other Crown Servants such as the Diplomatic and Secret Services (the Queen receives certain foreign intelligence reports before the prime minister does[6]).

- Judicial power is vested in the various judiciaries of the United Kingdom, who by constitution and statute[7] have judicial independence of the Government.

- The Church of England, of which the monarch is the head, has its own legislative, judicial and executive structures.

- Powers independent of government are legally granted to other public bodies by statute or Statutory Instrument such as an Order in Council, Royal Commission or otherwise.

The sovereign's role as a constitutional monarch is largely limited to non-partisan functions, such as granting honours. This role has been recognised since the 19th century. The constitutional writer Walter Bagehot identified the monarchy in 1867 as the "dignified part" rather than the "efficient part" of government.[8]

Appointment of the prime minister

Whenever necessary, the monarch is responsible for appointing a new prime minister (who by convention appoints and may dismiss every other Minister of the Crown, and thereby constitutes and controls the government). In accordance with unwritten constitutional conventions, the sovereign must appoint an individual who commands the support of the House of Commons, usually the leader of the party or coalition that has a majority in that House. The prime minister takes office by attending the monarch in private audience, and after "kissing hands" that appointment is immediately effective without any other formality or instrument.[9]

In a hung parliament where no party or coalition holds a majority, the monarch has an increased degree of latitude in choosing the individual likely to command the most support, though it would usually be the leader of the largest party.[10][11] Since 1945, there have only been three hung parliaments. The first followed the February 1974 general election when Harold Wilson was appointed Prime Minister after Edward Heath resigned following his failure to form a coalition. Although Wilson's Labour Party did not have a majority, they were the largest party. The second followed the May 2010 general election, in which the Conservatives (the largest party) and Liberal Democrats (the third largest party) agreed to form the first coalition government since World War II. The third occurred shortly thereafter, in June 2017, when the Conservative Party lost its majority in a snap election, though the party remained in power as a minority government.

Dissolution of Parliament

In 1950 the King's Private Secretary Sir Alan "Tommy" Lascelles, writing pseudonymously to The Times newspaper, asserted a constitutional convention: according to the Lascelles Principles, if a minority government asked to dissolve Parliament to call an early election to strengthen its position, the monarch could refuse, and would do so under three conditions. When Harold Wilson requested a dissolution late in 1974, the Queen granted his request as Heath had already failed to form a coalition. The resulting general election gave Wilson a small majority.[12] The monarch could in theory unilaterally dismiss the prime minister, but in practice the prime minister's term nowadays comes to an end only by electoral defeat, death, or resignation. The last monarch to remove the prime minister was William IV, who dismissed Lord Melbourne in 1834.[13] The Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 removed the monarch's authority to dissolve Parliament; however the Act specifically retained the monarch's power of prorogation, which is a regular feature of the parliamentary calendar.

Royal prerogative

Some of the government's executive authority is theoretically and nominally vested in the sovereign and is known as the royal prerogative. The monarch acts within the constraints of convention and precedent, exercising prerogative only on the advice of ministers responsible to Parliament, often through the prime minister or Privy Council.[14] In practice, prerogative powers are exercised only on the prime minister's advice – the prime minister, and not the sovereign, has control. The monarch holds a weekly audience with the prime minister; no records of these audiences are taken and the proceedings remain fully confidential.[15] The monarch may express his or her views, but, as a constitutional ruler, must ultimately accept the decisions of prime minister and the Cabinet (providing they command the support of the House). In Bagehot's words: "the sovereign has, under a constitutional monarchy ... three rights – the right to be consulted, the right to encourage, the right to warn."[16]

Although the royal prerogative is extensive and parliamentary approval is not formally required for its exercise, it is limited. Many Crown prerogatives have fallen out of use or have been permanently transferred to Parliament. For example, the monarch cannot impose and collect new taxes; such an action requires the authorisation of an Act of Parliament. According to a parliamentary report, "The Crown cannot invent new prerogative powers", and Parliament can override any prerogative power by passing legislation.[17]

The royal prerogative includes the powers to appoint and dismiss ministers, regulate the civil service, issue passports, declare war, make peace, direct the actions of the military, and negotiate and ratify treaties, alliances, and international agreements. However, a treaty cannot alter the domestic laws of the United Kingdom; an Act of Parliament is necessary in such cases. The monarch is the Head of the Armed Forces (the Royal Navy, the British Army, and the Royal Air Force), and accredits British High Commissioners and ambassadors, and receives heads of missions from foreign states.[17]

It is the prerogative of the monarch to summon and prorogue Parliament. Each parliamentary session begins with the monarch's summons. The new parliamentary session is marked by the State Opening of Parliament, during which the sovereign reads the Speech from the throne in the Chamber of the House of Lords, outlining the Government's legislative agenda.[18] Prorogation usually occurs about one year after a session begins, and formally concludes the session.[19] Dissolution ends a parliamentary term, and is followed by a general election for all seats in the House of Commons. A general election is normally held five years after the previous one under the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011, but can be held sooner if the prime minister loses a motion of confidence, or if two-thirds of the members of the House of Commons vote to hold an early election.

Before a bill passed by the legislative Houses can become law, the royal assent (the monarch's approval) is required.[20] In theory, assent can either be granted (making the bill law) or withheld (vetoing the bill), but since 1707 assent has always been granted.[21]

The monarch has a similar relationship with the devolved governments of Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. The sovereign appoints the First Minister of Scotland on the nomination of the Scottish Parliament,[22] and the First Minister of Wales on the nomination of the Senedd.[23] In Scottish matters, the sovereign acts on the advice of the Scottish Government. However, as devolution is more limited in Wales, in Welsh matters the sovereign acts on the advice of the prime minister and Cabinet of the United Kingdom. The sovereign can veto any law passed by the Northern Ireland Assembly, if it is deemed unconstitutional by the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland.[24]

The sovereign is deemed the "fount of justice"; although the sovereign does not personally rule in judicial cases, judicial functions are performed in his or her name. For instance, prosecutions are brought on the monarch's behalf, and courts derive their authority from the Crown. The common law holds that the sovereign "can do no wrong"; the monarch cannot be prosecuted for criminal offences. The Crown Proceedings Act 1947 allows civil lawsuits against the Crown in its public capacity (that is, lawsuits against the government), but not lawsuits against the monarch personally. The sovereign exercises the "prerogative of mercy", which is used to pardon convicted offenders or reduce sentences.[14][17]

The monarch is the "fount of honour", the source of all honours and dignities in the United Kingdom. The Crown creates all peerages, appoints members of the orders of chivalry, grants knighthoods and awards other honours.[25] Although peerages and most other honours are granted on the advice of the prime minister, some honours are within the personal gift of the sovereign, and are not granted on ministerial advice. The monarch alone appoints members of the Order of the Garter, the Order of the Thistle, the Royal Victorian Order and the Order of Merit.[26]

History

English monarchy

Following Viking raids and settlement in the ninth century, the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex emerged as the dominant English kingdom. Alfred the Great secured Wessex, achieved dominance over western Mercia, and assumed the title "King of the English".[27] His grandson Æthelstan was the first king to rule over a unitary kingdom roughly corresponding to the present borders of England, though its constituent parts retained strong regional identities. The 11th century saw England become more stable, despite a number of wars with the Danes, which resulted in a Danish monarchy for one generation.[28] The conquest of England in 1066 by William, Duke of Normandy, was crucial in terms of both political and social change. The new monarch continued the centralisation of power begun in the Anglo-Saxon period, while the Feudal System continued to develop.[29]

William was succeeded by two of his sons: William II, then Henry I. Henry made a controversial decision to name his daughter Matilda (his only surviving child) as his heir. Following Henry's death in 1135, one of William I's grandsons, Stephen, laid claim to the throne and took power with the support of most of the barons. Matilda challenged his reign; as a result, England descended into a period of disorder known as the Anarchy. Stephen maintained a precarious hold on power but agreed to a compromise under which Matilda's son Henry would succeed him. Henry accordingly became the first Angevin king of England and the first monarch of the Plantagenet dynasty as Henry II in 1154.[30]

The reigns of most of the Angevin monarchs were marred by civil strife and conflicts between the monarch and the nobility. Henry II faced rebellions from his own sons, the future monarchs Richard I and John. Nevertheless, Henry managed to expand his kingdom, forming what is retrospectively known as the Angevin Empire. Upon Henry's death, his elder son Richard succeeded to the throne; he was absent from England for most of his reign, as he left to fight in the Crusades. He was killed besieging a castle, and John succeeded him.

John's reign was marked by conflict with the barons, particularly over the limits of royal power. In 1215, the barons coerced the king into issuing Magna Carta (Latin for "Great Charter") to guarantee the rights and liberties of the nobility. Soon afterwards, further disagreements plunged England into a civil war known as the First Barons' War. The war came to an abrupt end after John died in 1216, leaving the Crown to his nine-year-old son Henry III.[31] Later in Henry's reign, Simon de Montfort led the barons in another rebellion, beginning the Second Barons' War. The war ended in a clear royalist victory and in the death of many rebels, but not before the king had agreed to summon a parliament in 1265.[32]

The next monarch, Edward Longshanks, was far more successful in maintaining royal power and responsible for the conquest of Wales. He attempted to establish English domination of Scotland. However, gains in Scotland were reversed during the reign of his successor, Edward II, who also faced conflict with the nobility.[33] In 1311, Edward II was forced to relinquish many of his powers to a committee of baronial "ordainers"; however, military victories helped him regain control in 1322.[34] Nevertheless, in 1327, Edward was deposed by his wife Isabella. His 14-year-old son became Edward III. Edward III claimed the French Crown, setting off the Hundred Years' War between England and France.

His campaigns conquered much French territory, but by 1374, all the gains had been lost. Edward's reign was also marked by the further development of Parliament, which came to be divided into two Houses. In 1377, Edward III died, leaving the Crown to his 10-year-old grandson Richard II. Like many of his predecessors, Richard II conflicted with the nobles by attempting to concentrate power in his own hands. In 1399, while he was campaigning in Ireland, his cousin Henry Bolingbroke seized power. Richard was deposed, imprisoned, and eventually murdered, probably by starvation, and Henry became king as Henry IV.[35]

Henry IV was the grandson of Edward III and the son of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster; hence, his dynasty was known as the House of Lancaster. For most of his reign, Henry IV was forced to fight off plots and rebellions; his success was partly due to the military skill of his son, the future Henry V. Henry V's own reign, which began in 1413, was largely free from domestic strife, leaving the king free to pursue the Hundred Years' War in France. Although he was victorious, his sudden death in 1422 left his infant son Henry VI on the throne and gave the French an opportunity to overthrow English rule.[36]

The unpopularity of Henry VI's counsellors and his belligerent consort, Margaret of Anjou, as well as his own ineffectual leadership, led to the weakening of the House of Lancaster. The Lancastrians faced a challenge from the House of York, so called because its head, a descendant of Edward III, was Richard, Duke of York. Although the Duke of York died in battle in 1460, his eldest son, Edward IV, led the Yorkists to victory in 1461. The Wars of the Roses, nevertheless, continued intermittently during his reign and those of his son Edward V and brother Richard III. Edward V disappeared, presumably murdered by Richard. Ultimately, the conflict culminated in success for the Lancastrian branch led by Henry Tudor, in 1485, when Richard III was killed in the Battle of Bosworth Field.[37]

Now King Henry VII, he neutralised the remaining Yorkist forces, partly by marrying Elizabeth of York, a Yorkist heir. Through skill and ability, Henry re-established absolute supremacy in the realm, and the conflicts with the nobility that had plagued previous monarchs came to an end.[38] The reign of the second Tudor king, Henry VIII, was one of great political change. Religious upheaval and disputes with the Pope led the monarch to break from the Roman Catholic Church and to establish the Church of England (the Anglican Church).[39]

Wales – which had been conquered centuries earlier, but had remained a separate dominion – was annexed to England under the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542.[40] Henry VIII's son and successor, the young Edward VI, continued with further religious reforms, but his early death in 1553 precipitated a succession crisis. He was wary of allowing his Catholic elder half-sister Mary I to succeed, and therefore drew up a will designating Lady Jane Grey as his heiress. Jane's reign, however, lasted only nine days; with tremendous popular support, Mary deposed her and declared herself the lawful sovereign. Mary I married Philip of Spain, who was declared king and co-ruler. He pursued disastrous wars in France and she attempted to return England to Roman Catholicism (burning Protestants at the stake as heretics in the process). Upon her death in 1558, the pair were succeeded by her Protestant half-sister Elizabeth I. England returned to Protestantism and continued its growth into a major world power by building its navy and exploring the New World.[41]

Scottish monarchy

In Scotland, as in England, monarchies emerged after the withdrawal of the Roman empire from Britain in the early fifth century. The three groups that lived in Scotland at this time were the Picts in the north east, the Britons in the south, including the Kingdom of Strathclyde, and the Gaels or Scotti (who would later give their name to Scotland), of the Irish petty kingdom of Dál Riata in the west. Kenneth MacAlpin is traditionally viewed as the first king of a united Scotland (known as Scotia to writers in Latin, or Alba to the Scots).[42] The expansion of Scottish dominions continued over the next two centuries, as other territories such as Strathclyde were absorbed.

Early Scottish monarchs did not inherit the Crown directly; instead the custom of tanistry was followed, where the monarchy alternated between different branches of the House of Alpin. As a result, however, the rival dynastic lines clashed, often violently. From 942 to 1005, seven consecutive monarchs were either murdered or killed in battle.[43] In 1005, Malcolm II ascended the throne having killed many rivals. He continued to ruthlessly eliminate opposition, and when he died in 1034 he was succeeded by his grandson, Duncan I, instead of a cousin, as had been usual. In 1040, Duncan suffered defeat in battle at the hands of Macbeth, who was killed himself in 1057 by Duncan's son Malcolm. The following year, after killing Macbeth's stepson Lulach, Malcolm ascended the throne as Malcolm III.[44]

With a further series of battles and deposings, five of Malcolm's sons as well as one of his brothers successively became king. Eventually, the Crown came to his youngest son, David I. David was succeeded by his grandsons Malcolm IV, and then by William the Lion, the longest-reigning King of Scots before the Union of the Crowns.[45] William participated in a rebellion against King Henry II of England but when the rebellion failed, William was captured by the English. In exchange for his release, William was forced to acknowledge Henry as his feudal overlord. The English King Richard I agreed to terminate the arrangement in 1189, in return for a large sum of money needed for the Crusades.[46] William died in 1214, and was succeeded by his son Alexander II. Alexander II, as well as his successor Alexander III, attempted to take over the Western Isles, which were still under the overlordship of Norway. During the reign of Alexander III, Norway launched an unsuccessful invasion of Scotland; the ensuing Treaty of Perth recognised Scottish control of the Western Isles and other disputed areas.[47]

Alexander III's unexpected death in a riding accident in 1286 precipitated a major succession crisis. Scottish leaders appealed to King Edward I of England for help in determining who was the rightful heir. Edward chose Alexander's three-year-old Norwegian granddaughter, Margaret. On her way to Scotland in 1290, however, Margaret died at sea, and Edward was again asked to adjudicate between 13 rival claimants to the throne. A court was set up and after two years of deliberation, it pronounced John Balliol to be king. Edward proceeded to treat Balliol as a vassal, and tried to exert influence over Scotland. In 1295, when Balliol renounced his allegiance to England, Edward I invaded. During the first ten years of the ensuing Wars of Scottish Independence, Scotland had no monarch, until Robert the Bruce declared himself king in 1306.[48]

Robert's efforts to control Scotland culminated in success, and Scottish independence was acknowledged in 1328. However, only one year later, Robert died and was succeeded by his five-year-old son, David II. On the pretext of restoring John Balliol's rightful heir, Edward Balliol, the English again invaded in 1332. During the next four years, Balliol was crowned, deposed, restored, deposed, restored, and deposed until he eventually settled in England, and David remained king for the next 35 years.[49]

David II died childless in 1371 and was succeeded by his nephew Robert II of the House of Stuart. The reigns of both Robert II and his successor, Robert III, were marked by a general decline in royal power. When Robert III died in 1406, regents had to rule the country; the monarch, Robert III's son James I, had been taken captive by the English. Having paid a large ransom, James returned to Scotland in 1424; to restore his authority, he used ruthless measures, including the execution of several of his enemies. He was assassinated by a group of nobles. James II continued his father's policies by subduing influential noblemen but he was killed in an accident at the age of thirty, and a council of regents again assumed power. James III was defeated in a battle against rebellious Scottish earls in 1488, leading to another boy-king: James IV.[50]

In 1513 James IV launched an invasion of England, attempting to take advantage of the absence of the English King Henry VIII. His forces met with disaster at Flodden Field; the King, many senior noblemen, and hundreds of soldiers were killed. As his son and successor, James V, was an infant, the government was again taken over by regents. James V led another disastrous war with the English in 1542, and his death in the same year left the Crown in the hands of his six-day-old daughter, Mary I. Once again, a regency was established.

Mary, a Roman Catholic, reigned during a period of great religious upheaval in Scotland. As a result of the efforts of reformers such as John Knox, a Protestant ascendancy was established. Mary caused alarm by marrying her Catholic cousin, Lord Darnley, in 1565. After Lord Darnley's assassination in 1567, Mary contracted an even more unpopular marriage with the Earl of Bothwell, who was widely suspected of Darnley's murder. The nobility rebelled against the Queen, forcing her to abdicate. She fled to England, and the Crown went to her infant son James VI, who was brought up as a Protestant. Mary was imprisoned and later executed by the English queen Elizabeth I.[51]

Personal union and republican phase

Elizabeth I's death in 1603 ended Tudor rule in England. Since she had no children, she was succeeded by the Scottish monarch James VI, who was the great-grandson of Henry VIII's older sister and hence Elizabeth's first cousin twice removed. James VI ruled in England as James I after what was known as the "Union of the Crowns". Although England and Scotland were in personal union under one monarch – James I became the first monarch to style himself "King of Great Britain" in 1604[52] – they remained two separate kingdoms. James I's successor, Charles I, experienced frequent conflicts with the English Parliament related to the issue of royal and parliamentary powers, especially the power to impose taxes. He provoked opposition by ruling without Parliament from 1629 to 1640, unilaterally levying taxes and adopting controversial religious policies (many of which were offensive to the Scottish Presbyterians and the English Puritans). His attempt to enforce Anglicanism led to organised rebellion in Scotland (the "Bishops' Wars") and ignited the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. In 1642, the conflict between the King and English Parliament reached its climax and the English Civil War began.[53]

The Civil War culminated in the execution of the king in 1649, the overthrow of the English monarchy, and the establishment of the Commonwealth of England. Charles I's son, Charles II, was proclaimed King of Great Britain in Scotland, but he was forced to flee abroad after he invaded England and was defeated at the Battle of Worcester. In 1653, Oliver Cromwell, the most prominent military and political leader in the nation, seized power and declared himself Lord Protector (effectively becoming a military dictator, but refusing the title of king). Cromwell ruled until his death in 1658, when he was succeeded by his son Richard. The new Lord Protector had little interest in governing; he soon resigned.[54] The lack of clear leadership led to civil and military unrest, and for a popular desire to restore the monarchy. In 1660, the monarchy was restored and Charles II returned to Britain.[55]

Charles II's reign was marked by the development of the first modern political parties in England. Charles had no legitimate children, and was due to be succeeded by his Roman Catholic brother, James, Duke of York. A parliamentary effort to exclude James from the line of succession arose; the "Petitioners", who supported exclusion, became the Whig Party, whereas the "Abhorrers", who opposed exclusion, became the Tory Party. The Exclusion Bill failed; on several occasions, Charles II dissolved Parliament because he feared that the bill might pass. After the dissolution of the Parliament of 1681, Charles ruled without a Parliament until his death in 1685. When James succeeded Charles, he pursued a policy of offering religious tolerance to Roman Catholics, thereby drawing the ire of many of his Protestant subjects. Many opposed James's decisions to maintain a large standing army, to appoint Roman Catholics to high political and military offices, and to imprison Church of England clerics who challenged his policies. As a result, a group of Protestants known as the Immortal Seven invited James II's daughter Mary and her husband William III of Orange to depose the king. William obliged, arriving in England on 5 November 1688 to great public support. Faced with the defection of many of his Protestant officials, James fled the realm and William and Mary (rather than James II's Catholic son) were declared joint Sovereigns of England, Scotland and Ireland.[56]

James's overthrow, known as the Glorious Revolution, was one of the most important events in the long evolution of parliamentary power. The Bill of Rights 1689 affirmed parliamentary supremacy, and declared that the English people held certain rights, including the freedom from taxes imposed without parliamentary consent. The Bill of Rights required future monarchs to be Protestants, and provided that, after any children of William and Mary, Mary's sister Anne would inherit the Crown. Mary died childless in 1694, leaving William as the sole monarch. By 1700, a political crisis arose, as all of Anne's children had died, leaving her as the only individual left in the line of succession. Parliament was afraid that the former James II or his supporters, known as Jacobites, might attempt to reclaim the throne. Parliament passed the Act of Settlement 1701, which excluded James and his Catholic relations from the succession and made William's nearest Protestant relations, the family of Sophia, Electress of Hanover, next in line to the throne after his sister-in-law Anne.[57] Soon after the passage of the Act, William III died, leaving the Crown to Anne.

After the 1707 Acts of Union

After Anne's accession, the problem of the succession re-emerged. The Scottish Parliament, infuriated that the English Parliament did not consult them on the choice of Sophia's family as the next heirs, passed the Act of Security 1704, threatening to end the personal union between England and Scotland. The Parliament of England retaliated with the Alien Act 1705, threatening to devastate the Scottish economy by restricting trade. The Scottish and English parliaments negotiated the Acts of Union 1707, under which England and Scotland were united into a single Kingdom of Great Britain, with succession under the rules prescribed by the Act of Settlement.[58]

In 1714, Queen Anne was succeeded by her second cousin, and Sophia's son, George I, Elector of Hanover, who consolidated his position by defeating Jacobite rebellions in 1715 and 1719. The new monarch was less active in government than many of his British predecessors, but retained control over his German kingdoms, with which Britain was now in personal union.[59] Power shifted towards George's ministers, especially to Sir Robert Walpole, who is often considered the first British prime minister, although the title was not then in use.[60] The next monarch, George II, witnessed the final end of the Jacobite threat in 1746, when the Catholic Stuarts were completely defeated. During the long reign of his grandson, George III, Britain's American colonies were lost, the former colonies having formed the United States of America, but British influence elsewhere in the world continued to grow, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was created by the Acts of Union 1800.[61]

From 1811 to 1820, George III suffered a severe bout of what is now believed to be porphyria, an illness rendering him incapable of ruling. His son, the future George IV, ruled in his stead as Prince Regent. During the Regency and his own reign, the power of the monarchy declined, and by the time of his successor, William IV, the monarch was no longer able to effectively interfere with parliamentary power. In 1834, William dismissed the Whig Prime Minister, William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne, and appointed a Tory, Sir Robert Peel. In the ensuing elections, however, Peel lost. The king had no choice but to recall Lord Melbourne. During William IV's reign, the Reform Act 1832, which reformed parliamentary representation, was passed. Together with others passed later in the century, the Act led to an expansion of the electoral franchise and the rise of the House of Commons as the most important branch of Parliament.[62]

The final transition to a constitutional monarchy was made during the long reign of William IV's successor, Victoria. As a woman, Victoria could not rule Hanover, which only permitted succession in the male line, so the personal union of the United Kingdom and Hanover came to an end. The Victorian era was marked by great cultural change, technological progress, and the establishment of the United Kingdom as one of the world's foremost powers. In recognition of British rule over India, Victoria was declared Empress of India in 1876. However, her reign was also marked by increased support for the republican movement, due in part to Victoria's permanent mourning and lengthy period of seclusion following the death of her husband in 1861.[63]

Victoria's son, Edward VII, became the first monarch of the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha in 1901. In 1917, the next monarch, George V, changed "Saxe-Coburg and Gotha" to "Windsor" in response to the anti-German sympathies aroused by the First World War. George V's reign was marked by the separation of Ireland into Northern Ireland, which remained a part of the United Kingdom, and the Irish Free State, an independent nation, in 1922.[64]

Shared monarchy

During the twentieth century, the Commonwealth of Nations evolved from the British Empire. Prior to 1926, the British Crown reigned over the British Empire collectively; the Dominions and Crown Colonies were subordinate to the United Kingdom. The Balfour Declaration of 1926 gave complete self-government to the Dominions, effectively creating a system whereby a single monarch operated independently in each separate Dominion. The concept was solidified by the Statute of Westminster 1931,[65] which has been likened to "a treaty among the Commonwealth countries".[66]

The monarchy thus ceased to be an exclusively British institution, although it is often still referred to as "British" for legal and historical reasons and for convenience. The monarch became separately monarch of the United Kingdom, monarch of Canada, monarch of Australia, and so forth. The independent states within the Commonwealth would share the same monarch in a relationship likened to a personal union.[67][68][69][70]

George V's death in 1936 was followed by the accession of Edward VIII, who caused a public scandal by announcing his desire to marry the divorced American Wallis Simpson, even though the Church of England opposed the remarriage of divorcees. Accordingly, Edward announced his intention to abdicate; the Parliaments of the United Kingdom and of other Commonwealth countries granted his request. Edward VIII and any children by his new wife were excluded from the line of succession, and the Crown went to his brother, George VI.[71] George served as a rallying figure for the British people during World War II, making morale-boosting visits to the troops as well as to munitions factories and to areas bombed by Nazi Germany. In June 1948 George VI relinquished the title Emperor of India, although remaining head of state of the Dominion of India.[72]

At first, every member of the Commonwealth retained the same monarch as the United Kingdom, but when the Dominion of India became a republic in 1950, it would no longer share in a common monarchy. Instead, the British monarch was acknowledged as "Head of the Commonwealth" in all Commonwealth member states, whether they were realms or republics. The position is purely ceremonial, and is not inherited by the British monarch as of right but is vested in an individual chosen by the Commonwealth heads of government.[73][74] Member states of the Commonwealth that share the same person as monarch are informally known as Commonwealth realms.[73]

Monarchy in Ireland

In 1155 the only English pope, Adrian IV, authorised King Henry II of England to take possession of Ireland as a feudal territory nominally under papal overlordship. The pope wanted the English monarch to annex Ireland and bring the Irish church into line with Rome, despite this process already underway in Ireland by 1155.[75] An all-island kingship of Ireland had been created in 854 by Máel Sechnaill mac Máele Ruanaid. His last successor was Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair, who had become King of Ireland in early 1166, and exiled Diarmait Mac Murchada, King of Leinster. Diarmait asked Henry II for help, gaining a group of Anglo-Norman aristocrats and adventurers, led by Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, to help him regain his throne. Diarmait and his Anglo-Norman allies succeeded and he became King of Leinster again. De Clare married Diarmait's daughter, and when Diarmait died in 1171, de Clare became King of Leinster.[76] Henry was afraid that de Clare would make Ireland a rival Norman kingdom, so he took advantage of the papal bull and invaded, forcing de Clare and the other Anglo-Norman aristocrats in Ireland and the major Irish kings and lords to recognise him as their overlord.[77]

By 1541, King Henry VIII of England had broken with the Church of Rome and declared himself Supreme Head of the Church of England. The pope's grant of Ireland to the English monarch became invalid, so Henry summoned a meeting of the Irish Parliament to change his title from Lord of Ireland to King of Ireland.[78]

In 1800, as a result of the Irish Rebellion of 1798, the Act of Union merged the kingdom of Great Britain and the kingdom of Ireland into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The whole island of Ireland continued to be a part of the United Kingdom until 1922, when what is now the Republic of Ireland won independence as the Irish Free State, a separate Dominion within the Commonwealth. The Irish Free State was renamed Éire (or "Ireland") in 1937, and in 1949 declared itself a republic, left the Commonwealth and severed all ties with the monarchy. Northern Ireland remained within the Union. In 1927, the United Kingdom changed its name to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, while the monarch's style for the next twenty years became "of Great Britain, Ireland and the British Dominions beyond the Seas, King, Defender of the Faith, Emperor of India".

Modern status

In the 1990s, republicanism in the United Kingdom grew, partly on account of negative publicity associated with the Royal Family (for instance, immediately following the death of Diana, Princess of Wales).[79] However, polls from 2002 to 2007 showed that around 70–80% of the British public supported the continuation of the monarchy.[80][81][82][83] This support has remained constant since then—according to a 2018 survey, a majority of the British public across all age groups still support the monarchy's continuation.[84]

Religious role

The sovereign is the supreme governor of the established Church of England. Archbishops and bishops are appointed by the monarch, on the advice of the prime minister, who chooses the appointee from a list of nominees prepared by a Church Commission. The Crown's role in the Church of England is titular; the most senior clergyman, the Archbishop of Canterbury, is the spiritual leader of the Church and of the worldwide Anglican Communion.[85][86] The monarch takes an oath to preserve the Church of Scotland and he or she holds the power to appoint the Lord High Commissioner to the Church's General Assembly, but otherwise plays no part in its governance, and exerts no powers over it.[87][88] The sovereign plays no formal role in the disestablished Church in Wales or Church of Ireland.

Succession

The relationship between the Commonwealth realms is such that any change to the laws governing succession to the shared throne requires the unanimous consent of all the realms. Succession is governed by statutes such as the Bill of Rights 1689, the Act of Settlement 1701 and the Acts of Union 1707. The rules of succession may only be changed by an Act of Parliament; it is not possible for an individual to renounce his or her right of succession. The Act of Settlement restricts the succession to the legitimate Protestant descendants of Sophia of Hanover (1630–1714), a granddaughter of James I.

Upon the death of a sovereign, their heir immediately and automatically succeeds (hence the phrase "The king is dead, long live the king!"), and the accession of the new sovereign is publicly proclaimed by an Accession Council that meets at St James's Palace.[89] Upon their accession, a new sovereign is required by law to make and subscribe several oaths: the Accession Declaration as first required by the Bill of Rights, and an oath that they will "maintain and preserve" the Church of Scotland settlement as required by the Act of Union. The monarch is usually crowned in Westminster Abbey, normally by the Archbishop of Canterbury. A coronation is not necessary for a sovereign to reign; indeed, the ceremony usually takes place many months after accession to allow sufficient time for its preparation and for a period of mourning.[90]

When an individual ascends the throne, it is expected they will reign until death. The only voluntary abdication, that of Edward VIII, had to be authorised by a special Act of Parliament, His Majesty's Declaration of Abdication Act 1936. The last monarch involuntarily removed from power was James VII and II, who fled into exile in 1688 during the Glorious Revolution.

Restrictions by gender and religion

Succession was largely governed by male-preference cognatic primogeniture, under which sons inherit before daughters, and elder children inherit before younger ones of the same gender. The British prime minister, David Cameron, announced at the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting 2011 that all 16 Commonwealth realms, including the United Kingdom, had agreed to abolish the gender-preference rule for anyone born after the date of the meeting, 28 October 2011.[91] They also agreed that future monarchs would no longer be prohibited from marrying a Roman Catholic – a law which dated from the Act of Settlement 1701. However, since the monarch is also the Supreme Governor of the Church of England, the law which prohibits a Roman Catholic from acceding to the throne remains.[92][93][94] The necessary UK legislation making the changes received the royal assent on 25 April 2013 and was brought into force in March 2015 after the equivalent legislation was approved in all the other Commonwealth realms.[95]

Though Catholics are prohibited from succeeding and are deemed "naturally dead" for succession purposes, the disqualification does not extend to the individual's legitimate Protestant descendants.

Regency

The Regency Acts allow for regencies in the event of a monarch who is a minor or who is physically or mentally incapacitated. When a regency is necessary, the next qualified individual in the line of succession automatically becomes regent, unless they themselves are a minor or incapacitated. Special provisions were made for Queen Elizabeth II by the Regency Act 1953, which stated that the Duke of Edinburgh (the Queen's husband) could act as regent in these circumstances.[96] Since reaching adulthood (in November 1966), Charles, Prince of Wales, has been first in line for the regency.

During a temporary physical infirmity or an absence from the kingdom, the sovereign may temporarily delegate some of his or her functions to Counsellors of State, the monarch's spouse and the first four adults in the line of succession. The present Counsellors of State are: the Duke of Edinburgh, the Prince of Wales, the Duke of Cambridge, the Duke of Sussex and the Duke of York.[97]

Finances

Until 1760 the monarch met all official expenses from hereditary revenues, which included the profits of the Crown Estate (the royal property portfolio). King George III agreed to surrender the hereditary revenues of the Crown in return for the Civil List, and this arrangement persisted until 2012. An annual Property Services grant-in-aid paid for the upkeep of the royal residences, and an annual Royal Travel Grant-in-Aid paid for travel. The Civil List covered most expenses, including those for staffing, state visits, public engagements, and official entertainment. Its size was fixed by Parliament every 10 years; any money saved was carried forward to the next 10-year period.[98] From 2012 until 2020, the Civil List and Grants-in-Aid are to be replaced with a single Sovereign Grant, which will be set at 15% of the revenues generated by the Crown Estate.[99]

The Crown Estate is one of the largest property portfolios in the United Kingdom, with holdings of £7.3 billion in 2011.[100] It is held in trust, and cannot be sold or owned by the sovereign in a private capacity.[101] In modern times, the profits surrendered from the Crown Estate to the Treasury have exceeded the Civil List and Grants-in-Aid.[98] For example, the Crown Estate produced £200 million in the financial year 2007–8, whereas reported parliamentary funding for the monarch was £40 million during the same period.[102]

Like the Crown Estate, the land and assets of the Duchy of Lancaster, a property portfolio valued at £383 million in 2011,[103] are held in trust. The revenues of the Duchy form part of the Privy Purse, and are used for expenses not borne by the parliamentary grants.[104] The Duchy of Cornwall is a similar estate held in trust to meet the expenses of the monarch's eldest son. The Royal Collection, which includes artworks and the Crown Jewels, is not owned by the sovereign personally and is held in trust,[105] as are the occupied palaces in the United Kingdom such as Buckingham Palace and Windsor Castle.[106]

The sovereign is subject to indirect taxes such as value-added tax, and since 1993 the Queen has paid income tax and capital gains tax on personal income. Parliamentary grants to the sovereign are not treated as income as they are solely for official expenditure.[107] Republicans estimate that the real cost of the monarchy, including security and potential income not claimed by the state, such as profits from the duchies of Lancaster and Cornwall and rent of Buckingham Palace and Windsor Castle, is £334 million a year.[108]

Estimates of the Queen's wealth vary, depending on whether assets owned by her personally or held in trust for the nation are included. Forbes magazine estimated her wealth at US$450 million in 2010,[109] but no official figure is available. In 1993, the Lord Chamberlain said estimates of £100 million were "grossly overstated".[110] Jock Colville, who was her former private secretary and a director of her bank, Coutts, estimated her wealth in 1971 at £2 million[111][112] (the equivalent of about £28 million today[113]).

Residences

The sovereign's official residence in London is Buckingham Palace. It is the site of most state banquets, investitures, royal christenings and other ceremonies.[114] Another official residence is Windsor Castle, the largest occupied castle in the world,[115] which is used principally at weekends, Easter and during Royal Ascot, an annual race meeting that is part of the social calendar.[115] The sovereign's official residence in Scotland is the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh. The monarch stays at Holyrood for at least one week each year, and when visiting Scotland on state occasions.[116]

Historically, the Palace of Westminster and the Tower of London were the main residences of the English Sovereign until Henry VIII acquired the Palace of Whitehall. Whitehall was destroyed by fire in 1698, leading to a shift to St James's Palace. Although replaced as the monarch's primary London residence by Buckingham Palace in 1837, St James's is still the senior palace[117] and remains the ceremonial Royal residence. For example, foreign ambassadors are accredited to the Court of St James's,[114][118] and the Palace is the site of the meeting of the Accession Council.[89] It is also used by other members of the Royal Family.[117]

Other residences include Clarence House and Kensington Palace. The palaces belong to the Crown; they are held in trust for future rulers, and cannot be sold by the monarch.[119] Sandringham House in Norfolk and Balmoral Castle in Aberdeenshire are privately owned by the Queen.[106]

Style

The present sovereign's full style and title is "Elizabeth the Second, by the Grace of God, of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and of Her other Realms and Territories Queen, Head of the Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith".[120] The title "Head of the Commonwealth" is held by the Queen personally, and is not vested in the British Crown.[74] Pope Leo X first granted the title "Defender of the Faith" to King Henry VIII in 1521, rewarding him for his support of the Papacy during the early years of the Protestant Reformation, particularly for his book the Defence of the Seven Sacraments.[121] After Henry broke from the Roman Church, Pope Paul III revoked the grant, but Parliament passed a law authorising its continued use.[122]

The sovereign is known as "His Majesty" or "Her Majesty". The form "Britannic Majesty" appears in international treaties and on passports to differentiate the British monarch from foreign rulers.[123][124] The monarch chooses his or her regnal name, not necessarily his or her first name – George VI, Edward VII and Victoria did not use their first names.[125]

If only one monarch has used a particular name, no ordinal is used; for example, Queen Victoria is not known as "Victoria I", and ordinals are not used for English monarchs who reigned before the Norman conquest of England. The question of whether numbering for British monarchs is based on previous English or Scottish monarchs was raised in 1953 when Scottish nationalists challenged the Queen's use of "Elizabeth II", on the grounds that there had never been an "Elizabeth I" in Scotland. In MacCormick v Lord Advocate, the Scottish Court of Session ruled against the plaintiffs, finding that the Queen's title was a matter of her own choice and prerogative. The Home Secretary told the House of Commons that monarchs since the Acts of Union had consistently used the higher of the English and Scottish ordinals, which in the applicable four cases has been the English ordinal.[126] The prime minister confirmed this practice, but noted that "neither The Queen nor her advisers could seek to bind their successors".[127] Future monarchs will apply this policy.[128]

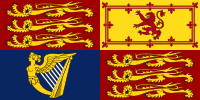

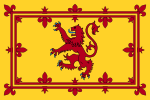

Arms

The Royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom are "Quarterly, I and IV Gules three lions passant guardant in pale Or [for England]; II Or a lion rampant within a double tressure flory-counter-flory Gules [for Scotland]; III Azure a harp Or stringed Argent [for Ireland]". The supporters are the Lion and the Unicorn; the motto is "Dieu et mon droit" (French: "God and my Right"). Surrounding the shield is a representation of a Garter bearing the motto of the Chivalric order of the same name; "Honi soit qui mal y pense". (Old French: "Shame be to him who thinks evil of it"). In Scotland, the monarch uses an alternative form of the arms in which quarters I and IV represent Scotland, II England, and III Ireland. The mottoes are "In Defens" (an abbreviated form of the Scots "In My Defens God Me Defend") and the motto of the Order of the Thistle; "Nemo me impune lacessit". (Latin: "No-one provokes me with impunity"); the supporters are the unicorn and lion, who support both the escutcheon and lances, from which fly the flags of Scotland and England.

.svg.png)

The monarch's official flag in the United Kingdom is the Royal Standard, which depicts the Royal Arms in banner form. It is flown only from buildings, vessels and vehicles in which the sovereign is present.[129] The Royal Standard is never flown at half-mast because there is always a sovereign: when one dies, his or her successor becomes the sovereign instantly.[130]

The Royal Standard of the United Kingdom: The Monarch's official flag

The Royal Standard of the United Kingdom: The Monarch's official flag.svg.png) The Royal Standard of the United Kingdom as used in Scotland

The Royal Standard of the United Kingdom as used in Scotland

When the monarch is not in residence, the Union Flag is flown at Buckingham Palace, Windsor Castle and Sandringham House, whereas in Scotland the Royal Standard of Scotland is flown at Holyrood Palace and Balmoral Castle.[129]

Union Flag of the United Kingdom

Union Flag of the United Kingdom The Royal Standard of Scotland

The Royal Standard of Scotland

See also

- States headed by Elizabeth II

Notes

- Symbols of the Monarchy: Coinage and bank notes, Official website of the British Monarchy, retrieved 18 June 2010

- Aslet, Clive (21 May 2014), "Our picture of Her Majesty will never fade", The Telegraph, retrieved 30 October 2018

- Symbols of the Monarchy: National Anthem, Official website of the British Monarchy, archived from the original on 2 September 2014, retrieved 18 June 2010

- e.g. Citizenship ceremonies, Home Office: UK Border Agency, retrieved 10 October 2008

- Crown Appointments Act 1661 c.6

- "In London, the revelations from [1989 Soviet defector Vladimir] Pasechnik were summarized into a quick note for the Joint Intelligence Committee. The first recipient of such reports is always Her Majesty, The Queen. The second is the prime minister, who at the time was [Margaret] Thatcher." Hoffman, David E. (Emanuel), The Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and Its Dangerous Legacy (N.Y.: Doubleday, 1st ed. [1st printing?] (ISBN 978-0-385-52437-7) 2009), p. 336 (author contributing editor & formerly U.S. White House, diplomatic, & Jerusalem correspondent, Moscow bureau chief, & foreign news asst. managing editor for The Wash. Post).

- s3. Constitutional Reform Act 2005

- Bagehot, p. 9.

- Brazier, p. 312.

- Waldron, pp.59–60

- Queen and Prime Minister, Official website of the British Monarchy, archived from the original on 14 April 2010, retrieved 18 June 2010

- Results and analysis: General election, 10 October 1974, Political Science Resources, 11 March 2008, retrieved 10 October 2008

- Brock, Michael (September 2004; online edition, January 2008). "William IV (1765–1837)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 10 October 2008 (subscription required)

- Durkin, Mary; Gay, Oonagh (21 December 2005), The Royal Prerogative (PDF), House of Commons Library, archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2008, retrieved 10 October 2008

- The Queen's working day > Evening, retrieved 11 March 2013

- Bagehot, p.75

- PASC Publishes Government Defence of its Sweeping Prerogative Powers, UK Parliament, 2002, archived from the original on 4 January 2004, retrieved 10 October 2008

- About Parliament: State Opening of Parliament, UK Parliament, 2008, archived from the original on 19 November 2002, retrieved 27 April 2008

- A Guide to Prorogation, BBC News, 7 November 2007, retrieved 27 April 2008

- Crabbe, p.17

- Royal Assent, BBC News, 24 January 2006, retrieved 27 April 2008

- UK Politics: Dewar appointed First Minister, BBC News, 17 May 1999, retrieved 10 October 2008

- Brief overview – Government of Wales Act 2006, Welsh Assembly Government, archived from the original on 26 October 2011, retrieved 30 August 2011

- Northern Ireland Act 1998, Office of Public Sector Information, retrieved 10 October 2008

- Dyer, Clare (21 October 2003), "Mystery lifted on Queen's powers", The Guardian, retrieved 9 May 2008

- Orders of Chivalry, The UK Honours System, 30 April 2007, archived from the original on 19 August 2007, retrieved 9 May 2008

- Cannon and Griffiths, pp.12–13 and 31

- Cannon and Griffiths, pp.13–17

- Cannon and Griffiths, pp.102–127

- Fraser, pp.30–46

- Fraser, pp.54–74

- Fraser, pp.77–78

- Fraser, pp.79–93

- Ashley, pp.595–597

- Fraser, pp.96–115

- Fraser, pp.118–130

- Fraser, pp.133–165

- Cannon and Griffiths, p.295; Fraser, pp.168–176

- Fraser, pp.179–189

- Cannon and Griffiths, pp.194, 265, 309

- Ashley, pp.636–647 and Fraser, pp.190–211

- Cannon and Griffiths, pp.1–12, 35

- Weir, pp.164–177

- Ashley, pp.390–395

- Ashley, pp.400–407 and Weir, pp.185–198

- Cannon and Griffiths, p.170

- Ashley, pp.407–409 and Cannon and Griffiths, pp.187, 196

- Ashley, pp.409–412

- Ashley, pp.549–552

- Ashley, pp.552–565

- Ashley, pp.567–575

- Royal Arms, Styles, and Titles of Great Britain: Westminster, 20 October 1604

- Fraser, pp.214–231

- Cannon and Griffiths, pp.393–400

- Fraser, p.232

- Fraser, pp.242–245

- Cannon and Griffiths, pp.439–440

- Cannon and Griffiths, pp.447–448

- Cannon and Griffiths, pp.460–469

- Sir Robert Walpole, BBC, retrieved 14 October 2008

- Ashley, pp.677–680

- Cannon and Griffiths, pp.530–550

- Fraser, pp.305–306

- Fraser, pp.314–333

- Statute of Westminster 1931, Government of Nova Scotia, 11 October 2001, retrieved 20 April 2008

- Justice Rouleau in O'Donohue v. Canada, 2003 CanLII 41404 (ON S.C.)

- Zines, Leslie (2008). The High Court and the Constitution, 5th ed. Annandale, New South Wales: Federation Press. ISBN 978-1-86287-691-0. p.314

- Corbett, P. E. (1940), "The Status of the British Commonwealth in International Law", The University of Toronto Law Journal, 3 (2): 348–359, doi:10.2307/824318, JSTOR 824318

- Scott, F. R. (January 1944), "The End of Dominion Status", The American Journal of International Law, 38 (1): 34–49, doi:10.2307/2192530, JSTOR 2192530

- R v Foreign Secretary; Ex parte Indian Association, (1982). QB 892 at 928; as referenced in High Court of Australia: Sue v Hill HCA 30; 23 June 1999; S179/1998 and B49/1998

- Matthew, H. C. G. (September 2004), "Edward VIII", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/31061, retrieved 20 April 2008

- Matthew, H. C. G. (September 2004), "George VI", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33370, retrieved 20 April 2008

- Boyce, Peter John (2008). The Queen's Other Realms: The Crown and Its Legacy in Australia, Canada and New Zealand. Federation Press. p. 41. ISBN 9781862877009. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- Head of the Commonwealth, Commonwealth Secretariat, archived from the original on 6 July 2010, retrieved 26 September 2008

- Sayer, Jane E. (September 2004), "Adrian IV", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/173, retrieved 20 April 2008 (Subscription required)

- Flanagan, M. T. (September 2004), "Dermot MacMurrough", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/17697, retrieved 20 April 2008 (Subscription required)

- Flanagan, M. T. (2004), "Clare, Richard fitz Gilbert de, second earl of Pembroke (c.1130–1176)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/17697, retrieved 14 October 2008 (Subscription required)

- Ives, E. W. (September 2004), "Henry VIII", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12955, retrieved 20 April 2008 (Subscription required)

- Seely, Robert (5 September 1997), Can the Windsors survive Diana's death?, Britannia Internet Magazine, archived from the original on 10 April 2011, retrieved 20 April 2008

- Grice, Andrew (9 April 2002), "Polls reveal big rise in support for monarchy", The Independent, retrieved 20 April 2008

- Monarchy poll, Ipsos MORI, April 2006, retrieved 6 August 2016

- Monarchy Survey (PDF), Populus Ltd, 14–16 December 2007, p. 9, archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2011, retrieved 30 November 2011

- Poll respondents back UK monarchy, BBC, 28 December 2007, retrieved 30 November 2011

- "Support for the monarchy in Britain by age 2018 survey". Statista. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- Queen and the Church of England, Official website of the British Monarchy, archived from the original on 2 December 2010, retrieved 18 June 2010

- Roles and Responsibilities: Overview, The Archbishop of Canterbury, archived from the original on 3 August 2008, retrieved 9 October 2008

- Queen and Church of Scotland, Official website of the British Monarchy, archived from the original on 2 December 2010, retrieved 18 June 2010

- Queen, State and Kirk, Church of Scotland official website, archived from the original on 17 April 2009, retrieved 10 May 2009

- Accession, Official website of the British Monarchy, archived from the original on 31 May 2015, retrieved 14 May 2009

- Coronation, Official website of the British Monarchy, retrieved 14 May 2009

- "Girls Equal in British throne succession", BBC News, British Broadcasting Corporation, 28 October 2011, retrieved 28 October 2011

- Act of Settlement 1700(c.2), Article II, retrieved 14 May 2010

- Union with Scotland Act 1706 (c.11), Article II, retrieved 14 May 2010

- Union with England Act 1707 (c.7), Article II, retrieved 14 May 2010

- Baby destined to become a monarch, ITV News, 22 July 2013, retrieved 7 November 2013

- Regency Act 1953, Ministry of Justice, retrieved 9 October 2008

- Queen and Government: Counsellors of State, Official website of the British Monarchy, retrieved 18 June 2010

- Royal Finances: The Civil List, Official web site of the British Monarchy, retrieved 18 June 2010

- "Royal funding changes become law", BBC News, BBC, 18 October 2011

- About Us, Crown Estate, 6 July 2011, archived from the original on 1 September 2011, retrieved 1 September 2011

- FAQs, Crown Estate, archived from the original on 3 September 2011, retrieved 1 September 2011

- Royal Finances: Head of State Expenditure, Official web site of the British Monarchy, archived from the original on 14 May 2010, retrieved 18 June 2010

- Accounts, Annual Reports and Investments, Duchy of Lancaster, 18 July 2011, archived from the original on 12 October 2011, retrieved 18 August 2011

- Royal Finances: Privy Purse and Duchy of Lancaster, Official web site of the British Monarchy, retrieved 18 June 2010

- FAQs, Royal Collection, retrieved 30 March 2012

Royal Collection, Royal Household, retrieved 9 December 2009 - The Royal Residences: Overview, Royal Household, archived from the original on 1 May 2011, retrieved 9 December 2009

- Royal Finances: Taxation, Official web site of the British Monarchy, retrieved 18 June 2010

- "Royal finances". Republic. 30 December 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- Serafin, Tatiana (7 July 2010), "The World's Richest Royals", Forbes, retrieved 13 January 2011

- Darnton, John (12 February 1993), "Tax Report Leaves Queen's Wealth in Dark", The New York Times, retrieved 18 June 2010

- "£2m estimate of the Queen's wealth 'more likely to be accurate'", The Times: 1, 11 June 1971

- Pimlott, Ben (2001). The Queen: Elizabeth II and the Monarchy. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-255494-1, p. 401

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- "Buckingham Palace", Official website of the British Monarchy, The Royal Household, archived from the original on 27 March 2010, retrieved 14 July 2009

- "Windsor Castle", Official website of the British Monarchy, The Royal Household, retrieved 14 July 2009

- "The Palace of Holyroodhouse", Official website of the British Monarchy, The Royal Household, retrieved 14 July 2009

- "Royal Residences: St. James's Palace", Official website of the British Monarchy, The Royal Household, retrieved 14 July 2009

- "Ambassadors credentials", Official website of the British Monarchy, The Royal Household, archived from the original on 9 March 2009, retrieved 14 July 2009

- A brief history of Historic Royal Palaces, Historic Royal Palaces, archived from the original on 18 December 2007, retrieved 20 April 2008

- Royal proclamation reciting the altered Style and Titles of the Crown

- Fraser, p.180

- Royal Styles: 1521–1553, Archontology, 18 August 2007, retrieved 10 October 2008

- "Passports". Official web site of the British Monarch. 15 January 2016. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- Thorpe, Robert (1819). A commentary on the treatises entered into between his Britannic majesty, and his most faithful majesty ... his catholic majesty ... and ... the king of the Netherlands ... for the purpose of preventing their subjects from engaging in any illicit traffic in slaves. p. 1. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- Panton, James (2011). Historical Dictionary of the British Monarchy. Scarecrow Press. p. 392. ISBN 9780810874978. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- Royal Titles Bill. Hansard, 3 March 1953, vol. 512, col. 251

- Royal Style and Title. Hansard, 15 April 1953, vol. 514, col. 199

- Debrett's, 2008 edition, p. 43

- Union Jack, The Royal Household, archived from the original on 5 November 2015, retrieved 9 May 2011

- Royal Standard, Official website of the British Monarchy, archived from the original on 28 December 2009, retrieved 18 June 2010

References

- Ashley, Mike (1998). The Mammoth Book of British Kings and Queens. London: Robinson. ISBN 1-84119-096-9.

- Bagehot, Walter; edited by Paul Smith (2001). The English Constitution. Cambridge University Press.

- Brazier, Rodney (1997). Ministers of the Crown. Oxford University Press.

- Brock, Michael (September 2004; online edition, January 2008). "William IV (1765–1837)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 22 April 2008 (subscription required).

- Castor, Helen (2010). She-Wolves: the Women who Ruled England Before Elizabeth. Faber and Faber.

- Cannon, John; Griffiths, Ralph (1988). The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Monarchy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822786-8

- Crabbe, V.C.R.A.C. (1994). Understanding Statutes. Cavendish Publishing. ISBN 978-1859411384

- Flanagan, M. T. (2004). "Mac Murchada, Diarmait (c.1110–1171)" and Clare, Richard fitz Gilbert de, second earl of Pembroke (c.1130–1176)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 14 October 2008 (subscription required).

- Fraser, Antonia (Editor) (1975). The Lives of the Kings & Queens of England. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-76911-1.

- Ives, E. W. (September 2004; online edition, January 2008). "Henry VIII (1491–1547)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 20 April 2008 (subscription required).

- Matthew, H. C. G. (2004). "Edward VIII (later Prince Edward, duke of Windsor) (1894–1972)" and "George VI (1895–1952)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 14 October 2008 (subscription required).

- Pimlott, Ben. The Queen: A Biography of Elizabeth II. (1998)

- Sayers, Jane E. (2004). "Adrian IV (d. 1159)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 20 April 2008 (subscription required).

- Tomkins, Adam (2003). Public Law. N.Y.: Oxford University Press (Clarendon Law ser.).

- Waldron, Jeremy (1990). The Law. Routledge.

- Weir, Alison (1996). Britain's Royal Families: The Complete Genealogy. (Revised edition). London: Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-7448-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to British monarchy. |