Here's an answer that doesn't involve much information theory or technical terminology:

Devices, be they telephones or modems, communicate over the phone lines by sending electricity down the line. The information is encoded by changing the levels of electricity on the wire. On a voice line, those changing levels correspond to the noises you're making into the microphone.

Anything that communicates on a wire, from a telegraph to a 1 Gbits/s Ethernet cable, in the end, communicates by putting pulses of electricity on the wire that the other end can detect.

The more information you want to send down the wire, the faster you have to vary the electrical signals. Morse code involves just a few changes per second, a voice conversation can involve changing the signals thousands of times per second, and high-speed Ethernet can involve tens of millions of changes per second.

The more changes per second you have, the more difficult the circuitry in between has to be, and the better-shielded the wires have to be, as miscellaneous transient disruptions cause more problems on higher-frequency signals.

When the telephone system was originally put together in the late 19th / early 20th century, the first question asked was, how good do we have to be? It was determined that as long as you're able to handle at least 6800 changes per second, (a signal up to 3400 Hz), audible audio will come through, though it will seem a bit 'stunted' - which is why telephones don't sound the same as regular conversation. This worked fine for a hundred years or so.

As computers became popular, people started using modems that made sounds on the line that corresponded to ones and zeroes, but the sounds had to correspond to the range of frequencies in the human voice, limiting them to a few kbits/s. As things improved, they eventually hit the limit of what a phone line can transmit; that limit is about 32 kbits/s, but a simple hack was quickly put in place to bump that up to 56 kbits/s.

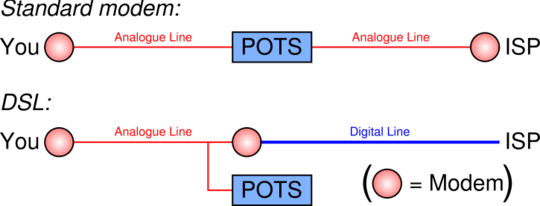

About that time, people also realized that you could use a short run of telephone cable to send much higher-frequency signals - up to a few miles when everything worked correctly, but certainly not the tens of miles that a regular phone signal could travel. By having special equipment at the phone company's end, and a DSL modem at the subscriber's end, they could send these special high-frequency signals down 'the last mile' over phone lines that were never really intended for them.

1Dial-up uses a phone line to dial a special phone number, while DSL utilizes technology to expand the phone line for broadband use. – Darius – 13 years ago

4Yes, the reason dial-up is slow is because its only capable of sending 64Kbps. Broadband is a great deal faster then 10 times that speed. – Ramhound – 13 years ago

66@Ramhound: So you are saying that dial-up is slow because it's slow. – user1686 – 13 years ago

19

I'll just leave this right here

– MDMarra – 13 years ago6As I understand it (in the UK), most/all telephone lines now carry all information digitally. The reason dial-up is slow is because the providers only allocate limited bandwidth to voice calls, and from their perspective, dial-up calls are voice calls. – FumbleFingers – 13 years ago