The best solutions involve changing your habits not to use rm directly.

One approach is to run echo rm -rf /stuff/with/wildcards* first. Check that the output from the wildcards looks reasonable, then use the shell's history to execute the previous command without the echo.

Another approach is to limit the echo command to cases where it's blindingly obvious what you'll be deleting. Rather than remove all the files in a directory, remove the directory and create a new one. A good method is to rename the existing directory to DELETE-foo, then create a new directory foo with appropriate permissions, and finally remove DELETE-foo. A side benefit of this method is that the command that's entered in your history is rm -rf DELETE-foo.

cd ..

mv somedir DELETE-somedir

mkdir somedir # or rsync -dgop DELETE-somedir somedir to preserve permissions

ls DELETE-somedir # just to make sure we're deleting the right thing

rm -rf DELETE-somedir

If you really insist on deleting a bunch of files because you need the directory to remain (because it must always exist, or because you wouldn't have the permission to recreate it), move the files to a different directory, and delete that directory.

mkdir ../DELETE_ME

mv * ../DELETE_ME

ls ../DELETE_ME

rm -rf ../DELETE_ME

(Hit that Alt+. key.)

Deleting a directory from inside would be attractive, because rm -rf . is short hence has a low risk of typos. Typical systems don't let you do that, unfortunately. You can to rm -rf -- "$PWD" instead, with a higher risk of typos but most of them lead to removing nothing. Beware that this leaves a dangerous command in your shell history.

Whenever you can, use version control. You don't rm, you cvs rm or whatever, and that's undoable.

Zsh has options to prompt you before running rm with an argument that lists all files in a directory: rm_star_silent (on by default) prompts before executing rm whatever/*, and rm_star_wait (off by default) adds a 10-second delay during which you cannot confirm. This is of limited use if you intended to remove all the files in some directory, because you'll be expecting the prompt already. It can help prevent typos like rm foo * for rm foo*.

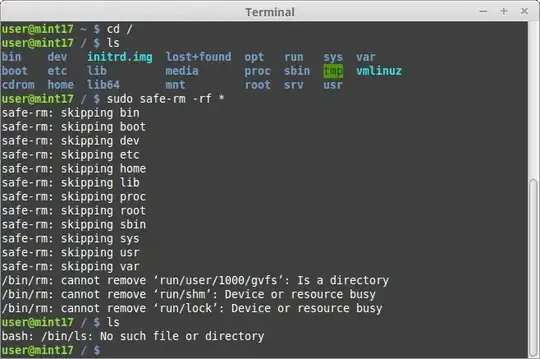

There are many more solutions floating around that involve changing the rm command. A limitation of this approach is that one day you'll be on a machine with the real rm and you'll automatically call rm, safe in your expectation of a confirmation… and next thing you'll be restoring backups.