This isn't really a great question for stackexchange as Google is keeping its algorithms secret so all we can really do is make guesses about how it works, but my understanding is that the new system will analyze your activity across all of Google's services (and possibly other sites that Google has some control over, such as websites that have Google ads).

Thus, it is likely that the checks are not limited to just the page that has the checkbox on it. For example, if they detect that your computer/IP address you are using was also used in the past to do things that a normal human would do - things like checking Gmail, searching on Google search, uploading files to Drive, sharing photos, browsing the web etc. - then it can probably be reasonably sure that you are a human and allow you to skip the image verification. On the other hand, if it can't associate your computer with any previous human-like activity, then it would be more suspicious and give you the image verification. Though the mouse behavior as it clicks the checkbox may be one factor it analyzes, there is almost certainly a lot more to it.

Again, we don't know for sure how it works. This is just my best guess based on what little Google has said:

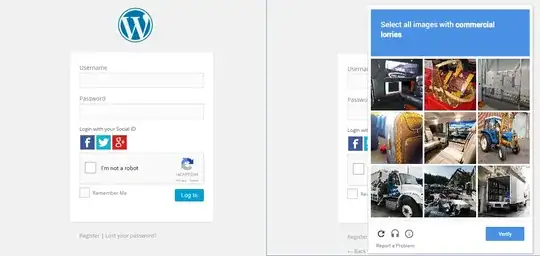

While the new reCAPTCHA API may sound simple, there is a high degree

of sophistication behind that modest checkbox. CAPTCHAs have long

relied on the inability of robots to solve distorted text. However,

our research recently showed that today’s Artificial Intelligence

technology can solve even the most difficult variant of distorted text

at 99.8% accuracy. Thus distorted text, on its own, is no longer a

dependable test.

To counter this, last year we developed an Advanced Risk Analysis

backend for reCAPTCHA that actively considers a user’s entire

engagement with the CAPTCHA—before, during, and after—to determine

whether that user is a human. This enables us to rely less on typing

distorted text and, in turn, offer a better experience for users. We

talked about this in our Valentine’s Day post earlier this year.

To me the point about "before, during, and after use" is a strong hint that they analyze previous browsing behavior, but my interpretation could be wrong.

Here's a quote from WIRED:

Instead of depending upon the traditional distorted word test,

Google’s “reCaptcha” examines cues every user unwittingly provides: IP

addresses and cookies provide evidence that the user is the same

friendly human Google remembers from elsewhere on the Web. And Shet

says even the tiny movements a user’s mouse makes as it hovers and

approaches a checkbox can help reveal an automated bot.

There is another thread on stackoverflow discussing this as well: https://stackoverflow.com/questions/27286232/how-does-new-google-recaptcha-work

As for image verification, you're not going to be able to find those images with reverse image search, or compile a database of them. They are usually random street signs or house numbers captured by Google's Street View cars, or words from books that were scanned for the Google Books project. There is a good purpose behind this - Google actually makes use of what people type into reCaptcha to improve their own databases and train OCR algorithms. reCaptcha gives the same image to a number of users, and if they all agree on what it says, then the picture becomes training data for Google's AI.

From wikipedia:

The reCAPTCHA service supplies subscribing websites with images of

words that optical character recognition (OCR) software has been

unable to read. The subscribing websites (whose purposes are generally

unrelated to the book digitization project) present these images for

humans to decipher as CAPTCHA words, as part of their normal

validation procedures. They then return the results to the reCAPTCHA

service, which sends the results to the digitization projects.

reCAPTCHA has worked on digitizing the archives of The New York Times

and books from Google Books.[3] As of 2012, thirty years of The New

York Times had been digitized and the project planned to have

completed the remaining years by the end of 2013. The now completed

archive of The New York Times can be searched from the New York Times

Article Archive, where more than 13 million articles in total have

been archived, dating from 1851 to the present day.