Revocation is the only method by which a certificate authority may propagate the information that a private key has been compromised. It is, in fact, a damage containment system: in the unfortunate event of a private key being stolen, the revocation system will make sure that nobody trusts the corresponding certificate more than one week or so after the theft is noticed and reported. If a client does not check revocation status, or bypasses it (as you are proposing to do), then this "one week" delay is extended to the expiration date of the certificate, which can be years away.

By definition, not checking revocation (or ignoring a failure to check revocation) weakens the system, so it cannot be said that it is "safe". But maybe it is not utterly risky. In practice, risks of connecting to a fake Web site are low, because stolen credit card numbers are not worth a lot, and running a fake Web site that successfully emulates a real airline reservation system is a lot of work; hackers who could steal the private key would probably not do that. But that's your decision to take, not mine.

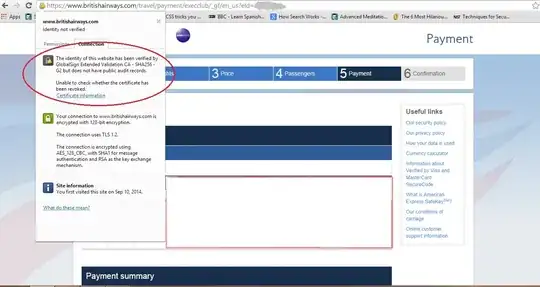

If your browser could not ascertain the revocation status, then chances are that you cannot do it yourself either. However, it may be interesting to know what exactly has happened. Normally, each certificate in the chain contains a URL to the location of the relevant CRL (in a CRL Distribution Points extension). Maybe some of these Web sites are currently unreachable; maybe the CRL they host are out of date, thus revealing a technical glitch on the CA side.

(From my machine, right now, the British Airways certificate looks fine, including revocation status, so chances are that the glitch was temporary.)