Today I was exploring a website used for keeping track of student grades and everything related to school. Basically like a school progress tracker for your child which is used by 90% of schools in my country.

I fired up Charles proxy and connected my phone to it and installed Charles's root certificate so I can use https (the site uses it). Anyway, I logged into the site and checked what Charles captured.

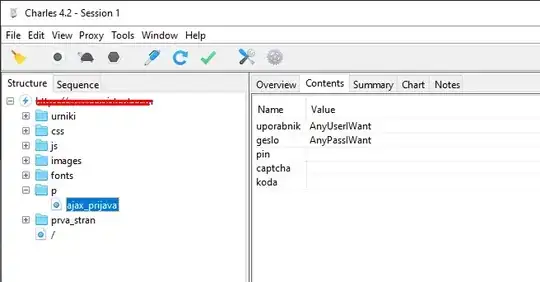

It captured a simple ajax call with 4 fields containing all the login credentials. Here's a screenshot:

Everything is even labeled - uporabnik means "user" and geslo means "password" So if I am understanding this correctly (I am really really just a beginner), everyone that manages to capture this can look at it?

Is this only possible with a proxy or can wireshark for example also do this and just capture packets over wifi?

Are my assumptions true and if they are, what should I do about it?