Assume that my Internet history is made public (accidentally or on purpose). And this release is over 24 hours since the visits were made.

Also, assume that there aren't embarrassing sites on there: there isn't any blackmail potential.

(My most embarrassing page visited in the last week is actually the TV tropes page for my little pony, for which I have a valid reason and a witness).

What potential attacks does this allow? I'm mildly concerned about seeing massive links like:

hxxps://kdp.amazon.com/en_US/ap-post-redirect?openid.assoc_handle=amzn_dtp&aToken=Atza%7CIwEBIO9mWoekr9KzK7rH_Db0gp93sewMCe6UcFPm_MbUhq-jp1m7kF-x0erh6NbjdLX3bm8Gfo3h7yU1nBYHOWso0LiOyUMLgLIDCEMGKGZBqv1EMyT6-EDajBYsH21sek92r5aH6Ahy9POCGEplpeKBVrAiU-vl3uIfOAHihKnB5r2yXPytFCITXM70wB5HBT-MIX3F1Y2G4WfWA-EgIfZY8bLdLangmgVq8hE61eDIFRzcSDtAf0Sz7_zxm1Ix8lV8XFBS8GSML9YSwZ1Gq6nSt9pG7hTZoGQns9nzKLk7WpAWE8RazDLKxVJD-nDsQ9VdBJe7JZJtD7c77swkYneOZ5HXgeGFkGhKsMnP7GSYndXhC_PqzY251iDt0X7e5TWvh86WZA0tG2qZ_lyIagZtB3iw&openid.claimed_id=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.amazon.com%2Fap%2Fid%2Famzn1.account.AEK7TIVVPUJDAK3JIFQIQ77WZWDQ&openid.identity=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.amazon.com%2Fap%2Fid%2Famzn1.account.AEK7TIVVPUJDAK3JIFQIQ77WZWDQ&openid.mode=id_res&openid.ns=http%3A%2F%2Fspecs.openid.net%2Fauth%2F2.0&openid.op_endpoint=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.amazon.com%2Fap%2Fsignin&openid.response_nonce=2018-12-11T13%3A46%3A52Z4004222742336216632&openid.return_to=https%3A%2F%2Fkdp.amazon.com%2Fap-post-redirect&openid.signed=assoc_handle%2CaToken%2Cclaimed_id%2Cidentity%2Cmode%2Cns%2Cop_endpoint%2Cresponse_nonce%2Creturn_to%2CsiteState%2Cns.pape%2Cpape.auth_policies%2Cpape.auth_time%2Csigned&openid.ns.pape=http%3A%2F%2Fspecs.openid.net%2Fextensions%2Fpape%2F1.0&openid.pape.auth_policies=http%3A%2F%2Fschemas.openid.net%2Fpape%2Fpolicies%2F2007%2F06%2Fnone&openid.pape.auth_time=2018-12-11T13%3A46%3A52Z&openid.sig=5cx5iHjeLyWTTA9iJ%2BucszunqanOw36djKuNF6%2FOfsM%3D&serial=&siteState=clientContext%3D135-4119325-2722413%2CsourceUrl%3Dhttps%253A%252F%252Fkdp.amazon.com%252Fbookshelf%253Flanguage%253Den_US%2Csignature%3DgqJ53erzurnmO1SPLDK1gLwh9%2FUP6rGUwGF2uZUAAAABAAAAAFwPv8dyYXcAAAAAAsF6s-obfie4v1Ep9rqj

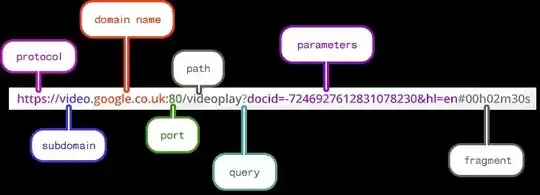

in my history and worrying that secure information might be passed in a URL somewhere.

I am aware that this makes it easier to impersonate my identity, and I'm mostly interested in the leakage of information via the URL itself.

I have a general interest, but this is motivated by a test project I'm running.