• Do you not have the alternative of just (i.e. only) having a recovery plan and process in case the attack in question does happen — a backup, so to speak?

Having said that… from your wording it looks as though you can suffer an attack of this type without even knowing it, unless you spend money just to be able to detect it. …So maybe the foregoing is a void concept.

• More subjectively, it looks as though this has that standard (and incredibly annoying) feature of difficult decisions, being that it involves unknowns. If you knew X (in this case, that an attack would/not happen), you would certainly do Y (in this case, spend lots of money on a counter, or not). Sometimes it can be helpful to acknowledge that you really do not have the information you need to inform which way you jump; then, you toss a coin and jump… as opposed to spending huge amounts of energy wringing your hands. (In extreme situations, human beings tend to behave on the basis that the eventuality will be what they would hope for, however unlikely it might be.)

There is value, for your staff, in just having a person to take the responsibility for the dark unknown.

I would like to give a nod to Will Barnwell’s answer (and the cited Nassim Taleb). Meaning absolutely no insult to “extensive philosophical argument//”… such are not necessarily correct. The issue for me is that it is easy to imagine that there might be two to three of these beasties within a few years, meaning that the cost of counter-measures rises from significant to crippling. Independently… if the risk can reasonably be expected to grow, then that changes the (given) parameters of the decision.

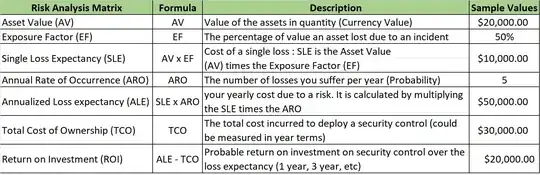

On the one side, we have the cost of the attack. As Philipp has observed, there is a maximum set by the value of the company; it would be misguided to spend $10m reconstructing a company that is worth only $1m. Unfortunately, this ignores the combined cost for the company’s customers. Whereas it is not sensible for a $1m business to value a potential problem at more than its own value, it remains true that the significance of the issue could easily be (say) $50m.

On the other side, there is the size of the risk. Again, an accountant (so to speak) might simply find out how many companies there are that are vulnerable to the attack type in question, and how many of these have been hit in each of the last few years, and directly derive a likelihood of any one company being hit in a given year. A slightly more sophisticated version would include making an estimate of how many were hit and managed to keep it a secret — if this is reasonably possible. A yet more sophisticated version would work out how many of these companies were worth attacking… which may or may not include the question of whether or not they individually have taken counter-measures… except that that would be a secret… and is, to some degree of likelihood, known to an attacker.

Then there is the possibility that, on the one side, a clever, cheap defence might become available and, on the other side, that the attackers might be more or less motivated or numerous in five years, or might find a vulnerability in a subset of the possible targets, and so on. Further, it may come to light that some companies are being attacked in this or a similar way, and do not know it (and some might find out after the event, if ever).

Further, there is the cumulative risk. It is all very well to calculate the risk as an annual figure, if the risk is reasonably high and the question is about how much to spend on preventing and mitigating it. If, conversely, the effect would be apt to take out the entire company, then an annualised figure is of less significance.

The OP said that this type of attack is rare, but does happen. The whole reason OP has put up a question on this site is that it is not true that the risk is vanishingly small, and it is not true that the risk is high enough to take for granted.

Let us imagine that the company decides to do nothing. Let us assume, further, that this is objectively reasonable (to an ideal observer). If it is hit in a few years, the cost will be devastating for not only the company but indeed many of its customers (I take it). There is a risk of this, that is not vanishingly, and possibly not trivially, small.

Let us imagine, conversely, that the company decides to spend significant amounts of money on preventing and mitigating this attack, and again that this is reasonable. If it is not hit, ever, the cost (of prevention) is significant to very significant. There was a risk of being attacked, but it was very small, and the money looks very much like a significant loss.

Finally, there is the possible quasi-catch-22 that the attackers will see, and look elsewhere, if it has countermeasures, and the converse.

I might also note that receiving an insurance payout that is (say) equal to the (accounting) value of the business is not apt to fix the problem if the lifeblood of the business — data — is lost or otherwise compromised.