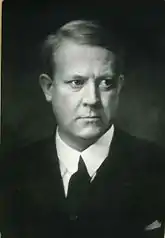

Vidkun Quisling

Vidkun Abraham Lauritz Jonssøn Quisling (1887–1945) is today most famous as the puppet "Minister President" of Norway during World War II.

| A lunatic Chaplin imitator and his greatest fans Nazism |

| First as tragedy |

| Then as farce |

|

v - t - e |

“”Vidkun Quisling: his name... means traitor. |

| —Narrator, "Nazi Collaborators: Vidkun Quisling" |

He originally was a humanitarian, but during one of his missions to Russia, he gained first hand experience on the evils of communism, although he praised Leon Trotsky and his Red Army. This led him to radicalise himself, first towards Mussolini's fascism and, later, to Hitler's nazism.

He might also have been a bigamist for a while.

Humanitarian work and other travels

His first trip outside the country was to Helsinki, Finland, where he went to be an "intelligence officer" (read: spy) at the Norwegian delegation.

Then, in 1922, famous explorer and humanitarian Fridtjof Nansen invited him to Kharkov, Ukraine, so he could help with humanitarian work there. Here he worked as a competent administrator, although a stubborn one, which would later came out to haunt him. In Ukraine, he met the first of his two wives, Alexandra Andreyevna Voronina, and married her there. He never loved her, and just wanted to lift her from poverty, so no boot-knocking there.

Leaving Ukraine, he came back in 1923, and met Maria Vasiljevna Pasetsjnikova, his second wife (maybe...). He really loved her, but... no boot-knocking there either...

In 1925, Nansen invited him to Armenia, to help him in a League of Nations-related resettlement project and (later) with the 1928 famine. He didn't succeed.

From 1928 to 1929, he became an ambassador to the Soviet Union, for both Norway and the UK. During this period, he became envolved in a ruble smuggling scandal and he also might have spied for the Brits (which was never substantiated).

Coming back to Norway

He became nuts, proposing the militarist Norsk Aktion ("Norwegian Action"). He also distorted Nansen's thought after he died, writing "Politiske tanker ved Fridtjof Nansens død" ("Political Thoughts on the Death of Fridtjof Nansen") for a newspaper, where he advocated, amongst other stuff, "strong and just government" and a "greater emphasis on race and heredity".

This was followed by a newspaper-serialised book, "Russland og vi" ("Russia and Ourselves"), which was openly racist and advocated a war against bolshevism. He founded a new movement, Nordisk folkereisning i Norge ("Rise of the Nordic people in Norway"), of which he was the fører (ain't it obvious what it means?).

This was before he became Minister of Defense in 1931. His colleagues didn't like him very much (he was suggested by an influential newspaper editor) and he became notorious for the 1931 "Battle of Menstad", a strike violently broken by the troops he sent in. He also accused the moderate social democratic Labour Party, along with the communists, of being (communist) traitors to Norway (oh the irony...). Additionally, in an event known as the Kullmann affair, he stripped pacifist Captain Olaf Kullmann of all his naval engagements after Kullmann participated in an anti-war congress in Amsterdam.

1932-1939

He and the prime minister butted heads on Quisling's handling of the Kullmann affair. He proposed a new political program for social and economic reform and demanded the resignation of the prime minister, even considering force to overthrow the government. In the end, it was the Liberal Party who brought him down.

In 1933, he transformed the Nordisk folkereisning i Norge movement into the fascist Nasjonal Samling ("National Unity") party, with the key aim of "establishing a strong and stable national government independent of ordinary party politics". Support for the party would grow overnight and, in the 1933 elections, they gained 2% of the vote, being the fifth largest Norwegian party but failing to elect a single candidate.

After this, Quisling's attitude towards compromise hardened, and the party started to decline. He would officially align the Nasjonal Samling with foreign fascist movements, especially the Nazi Party, and adopted an antisemitic attitude toward things he disliked (such as communism and liberalism). In the 1936 elections, the party would gain even fewer votes than in 1933. This split the party in two, and the Nasjonal Samling would become a fringe movement.

World War II

As his party was declining, he turned toward Hitler, whom he felt would need Norway as a naval base and could put him to power. So, in 1939, he had a personal audience with Hitler, where he proposed to launch a German-supported coup d'etat in Norway, after which Quisling's new government would invite Germany to set up naval bases in his home country. Meanwhile, Germany would fund Nasjonal Samling in order to gain support among the Norwegians.

Although Hitler found Quisling's plans a bit optimistic, he supported them, and Quisling received money for Nasjonal Samling. He also promised Quisling that any British invasion of Norway would be responded to with a German counter-invasion. Meanwhile, Quisling would pass on to Germany military secrets he knew from his time as Minister of Defense.

Invasion of Norway; coup d'etat attempt

In 9 April 1940, Germany invaded Norway by air and sea, and the government fled to Elverum in northern Norway. The Germans expected to capture the government and substitute it with Quisling's, but they failed.

A German envoy, Hans Wilhelm Scheidt, told Quisling that any government instituted by him would have Hitler's personal approval. So, late afternoon that day, claiming the legitimate government had fled Norway, he proclaimed his new government in what was the first coup d'etat announced by radio. His first orders as the new head of government were for the resistance to Germany to cease and for the arrest of the legitimate government.

The next day, German ambassador Curt Bräuer went to Elverum, where he demanded that King Haakon appoint Quisling the head of a new government (to legitimize the coup), but the King refused, preferring rather to abdicate than appoint Quisling.

With little popular support, and thus of little use to Hitler, Quisling was sidelined. However, Hitler told him that he shouldn't lose face, implying he could well be the future Norwegian leader.

The provisional puppet government

Hitler appointed German Josef Terboven as the new Norwegian Reichskommissar (a provisional governor) on 24 April, who answered directly to Hitler. Terboven didn't like Quisling very much, and wanted no room in a new government for him and the Nasjonal Samling. Eventually, Hitler pressured Terboven into accepting Quisling and his party.

Quisling was appointed the new acting prime minister under Terboven's wing, and the new government vowed to destroy "the destructive principles of the French Revolution", including pluralism and parliamentary rule. Mayors who joined his party were rewarded with greater powers.

In exchange for Norwegian independence under his government, Quisling agreed to raise soldiers to fight for Germany, which were organised as a special SS branch of his party.

He also aligned his government's policy on Jews with that of Germany's, but warned against extermination.

After a milk strike in September 1941, Quisling and the Germans cracked down on communists and trade unionists, a secret police was founded as an auxiliary to the Gestapo and radio sets were confiscated across the country. This led to an ostracism of Nasjonal Samling members from society.

Then, in January 1942, Terboven announced that the German administration would be wound down and Norway would become independent under Quisling. This would be postponed until February 1942, when his cabinet "elected" him Minister President.

The definitive puppet government

However, no independence occurred. He went to Berlin in 1942 to argue for Norwegian independence, but was not especially successful; Goebbels in particular was not convinced. Germany, however, reinforced his powers, albeit under Terboven's wing.

Meanwhile, in the summer of 1942, Quisling tried to force Norwegian youth to enter his party's youth wing, which prompted a mass resignation of teachers from their professional body and churchmen from their posts, along with large-scale civil unrest. He also went after bishop Eivind Berggrav. He was now more unpopular than ever, and organized resistance against him started. As a result, the independence negotiations stopped until the end of the war, and Quisling could not write more letters to Hitler. What a pity!

Then, the Germans became more heavy-handed in Trondheim, where there was widespread sabotage and two German police officers were killed. Quisling ordered the execution of police officer Gunnar Eilifsen when he refused to arrest five girls who did not show up for forced labor.

Additionally, the Germans ordered registration of the Jews, followed by their deportation. Following this, Germany deported Norwegian officers and finally attempted to deport students from the University of Oslo.

Meanwhile, Germany was losing the war, and Norwegian resistance was increasing. Quisling ordered compulsory military service on the members of his party's paramilitary, the Hird, after which some members resigned to avoid being drafted.

The end and the aftermath

After the liberation of Norway, Quisling was arrested by the resistance. He was accused of several crimes related to the coup, such as his revocation of the mobilisation order, to his time as Nasjonal Samling leader and to his actions as Minister President, such as assisting the enemy and illegally attempting to alter the constitution, Eilifsen's murder, more murders, theft, embezzlement and, most worrying of all for Quisling, the charge of conspiring with Hitler over the 9 April occupation of Norway.

He was found guilty and sentenced to death. He was executed by firing squad on 24 October 1945.

Despite, or perhaps because of, being one of the most despised Norwegians ever, he's also one the most written about. For decades after the war, the word quisling meant a traitor who sells out his country to foreign occupiers, although it has now mostly fallen out of use.

Scott Lively, The Pink Swastika and homosexuality claims

In this lecture, everyone's favourite *ahem* historian *ahem* Scott Lively says Quisling was a homosexual.

At least it gives us the reason for two wives, no boot-knocking...

Quisling apologetics

Even though he's so hated that his name is literally synonymous with "traitor", there are a few people who unironically defend him. They tend to claim that his actions somehow protected Norway from the worst occupation-related atrocities. This ignores the crimes he committed against Norwegians on his own account, as well as the small, insignificant detail that he helped getting the country occupied in the first place. He was also a pushover when it came to the Nazis' demands, so even if he was trying to be a "buffer" against them, he was an awful one. Quisling apologists also like to allege that he was abused while imprisoned, even though many of them don't seem terribly concerned about the very real torture endured by the victims of the Quisling regime.

Quisling apologists

- The fascists and neo-Nazis at solkorset.org,[1] Vigrid

File:Wikipedia's W.svg and the Nordic Resistance MovementFile:Wikipedia's W.svg . - Inger Cecilie Stridsklev, also a Nasjonal Samling apologist in general.

- Ralph Hewins

File:Wikipedia's W.svg painted an overly rosy portrait of him in his biography Quisling: Prophet without Honour, while vilifying the Norwegians who dared to hate the man who sold them out to the Nazis and headed a treasonous, tyrannical puppet regime. Predictably, the book was labelled pseudohistory and widely criticized in Norway. Unfortunately, English-speaking audiences tended to be more positive towards it.

See also

- Ragnar Skancke, one of his puppetry chums

References

- solkorset.org (in English). Warning: Nazism.