Modern art and architecture

Modern art and architecture is considered by many conservatives, such as Roger Scruton and Tom Wolfe,

| Thinking hardly or hardly thinking? Philosophy |

| Major trains of thought |

| The good, the bad and the brain fart |

| Come to think of it |

|

v - t - e |

At first glance, these conservatives would appear to have a point. Compare the works of Renoir

This judgment, however, is superficial and fails to take into account the vast and complex background of why modern art is what it is (and this is speaking only in the western context as many other cultures have long emphasized abstraction over photorealism such as East Asian artists).

Origins

People that complain about modern art's emphasis on abstraction tend to ignore the complex influences and history that paved the way for what we see today. What has influenced the rise of modern art in "the west" includes the following:

- Technological advancements including the invention of photography and video (which encouraged artists to observe how light works and interacts with color), paint tubes (which allowed artists to paint outdoors with oil paint and observe how light and atmosphere influence a scene), and new synthetic paint hues (which allowed varied and improved expression and emphasis of color) have vastly contributed of the move toward abstraction. Improved transportation and communication to other countries allow new ideas to influence western artists (such as Japonism's emphasis on essence of form and silhouette rather than photorealism reaching Impressionist artists). The value of scarcity of particular objects the elite possessed was threatened by the rise of these technologies, which enabled paintings to be reproduced with high accuracy and added the confidence of a purely mechanical process to portraiture; and lithography, which threatened to put near perfect copies of classic works of art on anybody's walls for pennies a print.

- Art has become more affordable, where it can reach a wider audience and be expressed more widely rather than serve as feel-good idealized propaganda for rich patrons, while patronage and commissions by the elite have diminished or at least changed. As Clement Greenberg

File:Wikipedia's W.svg realized, despite the veneer of Marxist orthodoxy on display in his famous essay on Avant-Garde and Kitsch,[1] the prestige of classical art was founded on the rarity of art objects, which enabled aristocratic patrons to control access and depiction to the unique items of beauty they owned. In this technological environment, the snob appeal of classical art was threatened. - Huge philosophical movements were underway as part of the consequences and awareness of socio-economic hardships including income inequality (the Realism (art movement)

File:Wikipedia's W.svg in the late 19th century showed a more realistic depiction of harsh realities of the working classes) and war (World War I and World War II in particular) that convinced artists to move away from the idealist and romanticized academic art. Scientific discoveries especially including light properties causing people to challenge and question what is "real" as well as what is "art". Hence, Impressionism, one of the foundations of modern art, has been more focused on exposing the artifice of art such as showing raw brushstrokes and paint texture as opposed to hiding them in traditional academic art (modern art developed further by emphasizing even more on color, spacing, shapes, and textures); it also emphasizes the fleeting and in-flux nature of light and color in observation rather than capturing a still image in a window as in academic art. A famous piece of work called Le Déjeuner sur l'herbeFile:Wikipedia's W.svg exemplifies this move toward challenging convention such as the frame size, perspective, the then-common techniques of disguising artifice, and idealization. The Treachery of ImagesFile:Wikipedia's W.svg helped push the idea that everything in art is representational and artificial. Some examples of philosophical movements are later discussed in the article, such as Dada's importance in contextualizing art and showing how we affix labels and meaning to objects.

Nonetheless, despite the democratization of art, this hasn't stopped the snobby elite for inventing means to exclude. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, with the rise of artistic modernism, one solution presented itself. Rarity and abstruseness of taste could be made to substitute for rarity of art objects since that horse had already left the barn.

Subject matter and narrative — historical figures, literary figures, idealized scenery or people — were disdained. The critics thought that people liked pictorial art because it told a story. The subject matter was important to the masses. The theory held that people liked pictures and statues of George Washington and Jesus because they liked George Washington and Jesus. They looked at paintings of historical figures and traditional narratives from history or literature and liked the paintings because they brought those figures and narratives to mind. These popular approaches to popular art were arbitrarily judged (Is there anything here but pointless snark and arrogance?):

Let us see, for example, what happens when an ignorant Russian peasant … stands with hypothetical freedom of choice before two paintings, one by Picasso, the other by Repin.

In the first he sees, let us say, a play of lines, colors and spaces that represent a woman. The abstract technique ... reminds him somewhat of the icons he has left behind him in the village, and he feels the attraction of the familiar. We will even suppose that he faintly surmises some of the great art values the cultivated find in Picasso.

He turns next to Repin's picture and sees a battle scene. The technique is not so familiar — as technique. But that weighs very little with the peasant, for he suddenly discovers values in Repin's picture that seem far superior to the values he has been accustomed to find in icon art; and the unfamiliar itself is one of the sources of those values: the values of the vividly recognizable, the miraculous and the sympathetic. In Repin's picture the peasant recognizes and sees things in the way in which he recognizes and sees things outside of pictures — there is no discontinuity between art and life, no need to accept a convention and say to oneself, that icon represents Jesus because it intends to represent Jesus, even if it does not remind me very much of a man. That Repin can paint so realistically that identifications are self-evident immediately and without any effort on the part of the spectator — that is miraculous.

The peasant is also pleased by the wealth of self-evident meanings which he finds in the picture: "it tells a story." Picasso and the icons are so austere and barren in comparison. What is more, Repin heightens reality and makes it dramatic: sunset, exploding shells, running and falling men. There is no longer any question of Picasso or icons. Repin is what the peasant wants, and nothing else but Repin. It is lucky, however, for Repin that the peasant is protected from the products of American capitalism, for he would not stand a chance next to a Saturday Evening Post cover by Norman Rockwell. [note 3]

[1] as a lesser and imperfect form of appreciation. "Retiring from public altogether, the avant-garde poet or artist sought to maintain the high level of his art by both narrowing and raising it to the expression of an absolute in which all relativities and contradictions would either be resolved or be beside the point. 'Art for art's sake' and 'pure poetry' appear, and subject-matter or content becomes something to be avoided like the plague."[1]

What was needed to keep out the riff-raff was to make the art obscure, hermetic, and needing a complicated education and complicated explanations before it could be fully understood. Once scarcity of art objects was threatened, rarity of taste became de rigeur. This gave rise to works of art that could not be fully appreciated without background knowledge that only a few ladies and gentlemen of leisure could be bothered to acquire. A taste for such art meant that you were the kind of person with money and leisure enough to learn to like it. By this artifice, the snob appeal of art was saved.[2].

This core belief of artistic modernity is itself problematic from the viewpoint of esthetic philosophy. You can jettison the literary, historical, and mythological references that informed classical and academic art. Understanding of these things, too, required knowledge; knowledge that was devalued by modernism. In order to keep contemporary art the bailiwick of an elite, the modernists succeeded only at replacing one kind of education needed to appreciate fine art with another. One result was an art world that was given to curious fads and phases, such as the odd concern with flatness

Dada

Dada was perhaps the first politically-inspired art movement, formed during the years of World War I, against war, bourgeois, nationalist and colonialist interests.[3] Some of the more prominent members included Marcel Duchamp,

Surrealism

The Surrealist art movement grew directly out of Dadaism in the 1920s, including Dadaists André Breton,

Degenerate art

It is one of history's many ironies that the concept of "degenerate art" was introduced by a Jew and prominent early Zionist, Max Nordau.

Nordau based his hypothesis upon the theories about eugenics and forensic phrenology by the Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso,

He attacked Aestheticism

Despite the fact that Nordau was Jewish and a key figure in the Zionist movement, his theory of artistic degeneracy would be seized upon by German National Socialists during the Weimar Republic as a rallying point for their anti-Semitic and racist demand for Aryan purity in art.

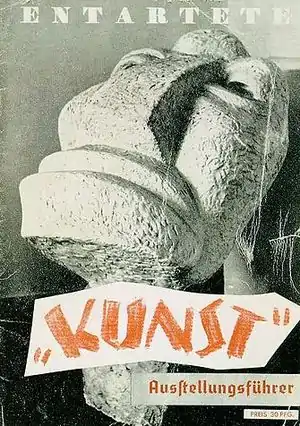

The Nazi Degenerate Art Exhibition

In 1937, the Nazi regime ran an art exhibition of "degenerate art"

Many of the works displayed here were cynically sold off, to mostly American collectors, after the exhibition, although approximately 5,000 works were destroyed. Joseph Goebbels wrote of them changing hands between U.S. collectors for "ten cents a kilo", although some "foreign exchange ... will go into the pot for war expenses, and after the war will be devoted to the purchase of art."[7] Some 1500 paintings were stolen by Hildebrand Gurlitt,

High modernism

“”If a planned social order is better than the accidental, irrational deposit of historical practice, two conclusions follow. Only those who have the scientific knowledge to discern and create this superior social order are fit to rule in the new age. Further, those who through retrograde ignorance refuse to yield to the scientific plan need to be educated to its benefits

or else swept aside. |

| —James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State, (Yale, 1998) p. 94 |

Clement Greenberg's contrast of the avant-garde versus kitsch suggests a mentality and dynamic that opposes elite tastes against popular tastes.[9] Occasionally, this contempt for the tastes of the masses was noticed by those masses, and drew angry retorts. This elitist conception of modernism has been labeled "high modernism", a label suggesting that this is the most extreme or characteristic form of modernism. Cultural critic Bram Dijkstra

“”Much of the post-WWII high modernism in America and the rest of the western world is antihumanist, hostile to notions of community, of any form of humanism. It becomes about the lack of meaning, the need to create our own significance out of nothing. The highest level of significance, that of the elite, becomes the abstraction. So the concept of the evolutionary elite arises again, deliberately excluding those who 'haven't evolved.'[10] |

This conflict between a self-proclaimed artistic elite and the masses has played out on a number of fronts.

“”The contemporary cult of the free market is just as radical an exercise in social engineering as many experiments in economic planning tried in this century. Like other kinds of high modernism, it rests on a confident ignorance of the immensely complex workings of real societies. |

| —- John Gray, The Best Laid Plans, New York Times, April 19, 1998 |

The Soviet Union versus the Second Viennese School

The Second Viennese School

During the years after World War II, serialism and atonality became near ubiquitous in Western concert music, which at this point was no longer underwritten by paying audiences or aristocratic patrons but had become a wing of academia. Greenberg's contempt for the taste of the masses was made explicit by composer Milton Babbitt,

From the 1950s through the 1970s, the academic serialist composers heaped scorn on their colleagues who dared to cling to tonality. Charles Wuorinen

In the Soviet Union, fortunately, some of the commissars were still proletarian enough that they would have none of this. Andrei Zhdanov,

However ham-fisted this government intervention in the creative process was, it had the result of making post-war Russian music much more listenable than contemporary productions of Western concert music, though not for lack of ham-fisted intervention in the creative process in the West, which, as previously explained, was not the case. The Russian composers whose work was the target of the anti-formalism campaign went on to compose works of abiding popularity, such as Shostakovich's Fifth Symphony in D Minor.

Of course, there were some composers outside the Soviet Union who resisted the strict taboo on classic tonality represented by strict dodecaphony; Copland wrote several pieces which, while based on tone rows, declined to rely solely upon the prime, inverse, retrograde, and retrograde inverse forms of those rows, and instead incorporated fragmented quotes thereof as a means of retaining more familiar harmonies.[18] He also wrote unambiguously tonal pieces on and off until his death. Likewise, Vaughn Williams more or less stuck to his guns until his death (1958), although he did often defy expectations in other ways. While serialism certainly exerted a strong influence over some media/types of ensemble, the then-ascendant wind ensemble continued to develop a largely non-serial repertoire more or less unmolested though arguably this is probably just because the Second Viennese School proper seems to largely have had nothing to do with the smaller wind instruments, and in no area was serialism wholly dominant.

Starting during the 1960s, other movements arose as well to escape the domineering strictures of Darmstädter serialism: examples include the minimalist style of Phillip Glass, Steve Reich and Terry Riley, the aleatoric and chance experiments of John Cage, and later, the spectral music of Gérard Grisey and Tristan Murail. By the 1980's, even a hardline serialist like Pierre Boulez had wearied of the rigors of hard serialism, and integrated the technique into a more fluid, expressive style.

Was the CIA responsible?

The revisionist historian Frances Stonor Saunders suggested, in her book The cultural cold war: the CIA and the world of arts and letters[19] that the Central Intelligence Agency secretly funded many of the Abstract Expressionist painters, serialist composers, and other modern artists in the post-war United States. Via the Congress for Cultural Freedom,

According to Saunders, the idea was to win the hearts and minds of the Western intelligentsia that followed these issues and turn them into intellectual allies in the Cold War and the struggle against Soviet communism. By publicizing the American artists' freedom to create drippy action paintings, atonal music, and other abstract arts free from any moral or political message, they meant to contrast the artistic vigor and freedom of the West versus political interference by Stalinist bureaucrats.

This really was a job that called for double-naught spies. A public State Department exhibition of modernist American art drew political blowback, with President Harry Truman scornfully remarking, "If that's art, then I'm a Hottentot."[20] In this climate, the message that America was a land of cultural vitality and friendly to intellectuals would need to be publicized by clandestine means. The newly formed CIA, staffed with young graduates of elite Ivy League colleges, was better suited for this mission than other agencies of the United States government. Nelson Rockefeller and other members of the Rockefeller family were alleged to have been the conduits of CIA patronage, via their seats on the board of the Museum of Modern Art

Others have dismissed this suggestion as a conspiracy theory. Michael Kimmelman has argued that these allegations are either flatly false or at minimum decontextualized.[21] And to some, like Henry Makow, it really was a conspiracy. The CIA was sponsoring abstract art on behalf of the Illuminati, who used abstract art to corrupt our moral fiber. "Modernism is a solipsism where the bankers' perversity[note 6] becomes the norm. For example, the CIA actively promoted modern abstract art, an art disconnected from human identity and aspirations, an art any child or monkey could produce."[22] Maybe it really was no conspiracy because, more than these allegations being either flatly false or at minimum decontextualized per se and in one of the greatest ironies of history, the Congress for Cultural Freedom ultimately did nothing but establish political counterorthodoxies of a paradoxical Social Democratic Nihilism more than publicize the American artists' freedom of expression per se. And they were even weak ones at that, never really dominating except at elite Ivy League colleges, whence the Director of Central Intelligence had drawn the staff of the newly formed CIA.

The International Style gets in your face

“” What sphinx of cement and aluminum bashed open their skulls and ate up their brains and imagination? Moloch! Solitude! Filth! Ugliness! Ashcans and unobtainable dollars! Children screaming under the stairways! Boys sobbing in armies! Old men weeping in the parks! Moloch! Moloch! Nightmare of Moloch! Moloch the loveless! Mental Moloch! Moloch the heavy judger of men! Moloch the incomprehensible prison! Moloch the crossbone soulless jailhouse and Congress of sorrows! Moloch whose buildings are judgment! Moloch the vast stone of war! Moloch the stunned governments! |

| — - Allen Ginsberg, Howl |

Bad architecture has a problem. If you don't get serialist or atonal music, you don't have to listen to it. Odds are your classical FM station doesn't play much of it anyways. If you find the abstract expressionist

This style was called the International Style

The International Style, like serialist music, arose in pre-war Germany and was fostered in the Bauhaus

A great deal of curious ideology surrounded the International Style at its creation. The most utopian of the founders of the International Style was the French architect Le Corbusier,

“”The object of this edict is to enlighten the present and future citizens of Chandigarh about the basic concepts of planning of the city so that they become its guardians and save it from whims of individuals. |

| —Le Corbusier, The Edict of Chandigarh |

Grand claims were made for his vision; he said that his design for the city "puts us in touch with the infinite cosmos and nature. It provides us with places and buildings for all human activities by which the citizens can live a full and harmonious life. Here the radiance of nature and heart are within our reach." Le Corbusier went on to collaborate with the Vichy regime of France during World War II, while also asking Mussolini to put him in charge of something radiant.

The Radiant City brought to earth

An attempt to enact the Radiant City on an even larger scale was done by Le Corbusier's student Lúcio Costa

“”Nothing dates faster than people's fantasies about the future. This is what you get when perfectly decent, intelligent, and talented men start thinking in terms of space rather than place; and single rather than multiple meanings. It's what you get when you design for political aspirations rather than real human needs. You get miles of jerry-built platonic nowhere infested with Volkswagens. This, one may fervently hope, is the last experiment of its kind. The utopian buck stops here. |

| —Robert Hughes, The Shock of the New, ep. 4, "Trouble in Utopia". |

As James C. Scott

“”The disorienting quality of Brasilia is exacerbated by architectural repetition and uniformity. Here is a case where what seems like rationality and legibility to those working in administration and urban services seems like mystifying disorder for the ordinary residents who must navigate the city. Brasilia has few landmarks. Each commercial quarter or superquadra cluster looks roughly like any other. The sectors of the city are designated by an elaborate set of acronyms and abbreviations that are nearly impossible to master, except from the global logic of the center. |

| —James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State (Yale, 1998), p. 127 |

The arrogance of urban renewal

The International Style, particularly in its later Brutalist

As Jane Jacobs

The urban planners, confident that their expertise was superior to that of the poor people who lived there, swept away these tenements and removed their residents into vast International Style high-rises. These projects were designed for privacy with hardly any visible public spaces. They were deliberately and intentionally separated from grocers, small restaurants and taverns, and other small businesses that formed part of the former urban mix. Moving the urban poor into these warrens often brought an epidemic of crime, like the ones that befell the notorious Cabrini–Green Homes

That said

Tom Wolfe was generally correct when he wrote in From Bauhaus to Our House that large blank concrete constructions are alienating, and architects need to take into account the people who live and work in the buildings they design. Wolfe's book became a standard text in architecture courses, to discourage architects from repeating the mistakes they were making. It didn't work. With the passage of time, some Brutalist buildings have actually become popular with the people who live or work in them, and many are now regarded as spectacularly photogenic, leading to a revival of interest in the style.[29]

See also

- Frankfurt School

- Cultural Marxism

- Futurism

- Fun:Dada

External links

- Mike Harman, The cultural Cold War: corporate and state intervention in the arts; libcom.org, Sept. 11, 2006. Alleges that the CIA funded serialist composers and abstract impressionist painters as part of an anti-Communist strategy.

- James C. Scott, The Trouble with the View from Above. Cato Unbound, Sept. 8, 2010.

Notes

- Technically, this is true because a child has drawn that several times. But it is involuntary when a child does it because a child has not learned craftsmanship or simple draftsmanship yet, whereas Picasso and Renoir have made a considered creative decision to do it.

- Here, for instance, Pierrot paints a picture of history's first royal gay wedding, apparently between two lesbians. They have weird pets. His canvas is held up by naked Hercules. To his right, a flying lady (we think it's a lady since androgynous figures are common in this sort of art) beats up a Roman soldier while being urged on by a second flying lady with a vuvuzela. Above, the Pope is hangin' with his baby mommas, drinkin' that wine. To the left, Lady Liberty shows off her legs to George Washington, who hugs his wild boar(?) in alarm, above another sadomasochistic scene, this time with cherubs. Everyone is young and attractive, things like wartime and religious authority are glorified, drama is over-the-top; this is characteristic of Baroque painting which the ultra-rich people that sponsor this painting love since there's no questioning anything.

- The argument would appear to be based on sneering at 'peasants', scoffing at our imaginary peasant's actually intelligent response to the two paintings, and assuming that the reader shares Greenberg's disdain for the art of Norman Rockwell. At least the implied irony of the Picasso painting representing the Modernist side of the argument appears not entirely lost on Greenberg, though, as he has correctly identified it as the milder end of the spectrum of Modernism where most of Picasso’s Modernist paintings sit.

- Sigmund Freud's theories about psychosexual development also owe much to Haeckel's goal-driven view of evolution.

- Arnold Schoenberg's Variations for Orchestra, Op. 31[11] is his first large-scale twelve-tone work. Berg's Violin Concerto[12] is one of the few tuneful twelve-tone works, since the piece openly makes allusions to tonality (contrary to Schoenberg's purpose of devising the system)

- Is this an antisemitic dog whistle or are we already seeing things?

- Indiana once had an industry of skilled stone cutters and carvers carving Corinthian capitals and other architectural details out of the celebrated Bedford limestone. When the use of classical decorative elements in architecture fell out of fashion, these skilled artisan jobs vanished. Walter S. Arnold, History of the Stonecutter's Union;[23] See the Wikipedia article on Indiana Limestone.

- Actually named after Le Corbusier's enthusiasm for béton brut, "bare concrete"; but if the shoe fits....

References

- Clement Greenberg, Avant-Garde and Kitsch. Partisan Review (1939)

- See generally, Tom Wolfe, The Painted Word (Farrar, Strauss, & Giroux, 1975)

- Richter, Hans (1965) Dada: Art and Anti-art, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0500200394.

- Surrealism, Art and Modern Science: Relativity, Quantum Mechanics, Epistemology by Gavin Parkinson, Yale University Press, 2008, 294 pp. ISBN 9780300098877.

- [http://www.surrealismcentre.ac.uk/papersofsurrealism/journal8/acrobat%20files/Book%20Reviews/Ambrosio%20final%2017.05.10.pdf A review of Surrealism, Art and Modern Science by Chiara Ambrosio (2010).

- Max Nordau, Degeneration. English translation, 1895.

- Frederic Spotts, 2002. Hitler and the Power of Aesthetics. The Overlook Press. pp. 151–68. ISBN 1-58567-507-5.

- "Nazi art treasure trove valued at £1BILLION is found in shabby Munich apartment". Daily Mail. Nov. 3, 2013

- Deniz Tekiner, Formalist art criticism and the politics of meaning. Social Justice, Jun 22, 2006.

- Interview with Bram Dijkstra, conducted by Ron Hogan, for beatrice.com.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NELOVT71prI

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gd0dMs0MTg8

- Milton Babbitt, "Who Cares If You Listen?". (High Fidelity, 1958)

- Milton Babbitt, String Quartet No. 2. (1954)

- Anthony Tommasini, Midcentury Serialists: The Bullies or the Besieged?. New York Times, July 9, 2000.

- Charles Wuorinen, String Quartet No. 1, 1971.

- Dmitri Shostakovich, Passacaglia from The Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District (Леди Макбет Мценского уезда), 1934.

- Listen, for example, to his Piano Fantasy, which he himself argued could be described as having an "over-all tonal orientation" despite "liberal use of devices associated with that [twelve-tone] technique."

- New York: New Press: Distributed by W.W. Norton & Co., 2000. ISBN 1-56584-596-X

- Frances Stonor Saunders, Modern art was CIA 'weapon', The Independent, Oct. 22, 1996.

- Michael Kimmelman, in Frascina, Francis, ed. (2000). "Revisiting the Revisionists: The Modern, Its Critics, and the Cold War". Pollock and After: The Critical Debate. Psychology Press. pp. 294–306. ISBN 9780415228664.

- Henry Makow, How the Illuminati Control Culture, October 6, 2013.

- http://www.stonecarver.com/union.html

- Philip S. Gutis, It's Ugly, And So Is The Fight To Save It, New York Times, February 7, 1987, accessed 02-17-2008

- E.g., C. Thau & K. Vindum, Jacobsen, 2002, at 65, ISBN 978-87-7407-230-0 (referring to reaction to internationalism as "A Horror of the Traceless, Inhuman Industrial Look")

- A History of Architecture, New Internationalist issue 202 — December 1989

- T. Wolfe, From Bauhaus to Our House, Farrar Straus Giroux (1981), ISBN 978-0-374-15892-7 ISBN 0-374-15892-4

- Jonathan Glancey, Life after carbuncles, The Guardian, May 17, 2004.

- Why Brutalist Architecture Is So Hard to Love by Roman Mars (99% Invisible) (Aug. 13 2015 9:27 AM) Slate.