Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (Born January 7 1800 - Died March 8 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853 after Zachary Taylor (for whom he was Vice President) died in office, the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. He also ran in 1856 as a Know Nothing, winning 21.5% of the vote but only winning Maryland. His spouse was Caroline Carmichael McIntosh Fillmore. He often has a reputation as having a name that most people can recognize as belonging to a president, but with nobody able to remember anything he actually did. His presidency is a great example of how being a centrist can backfire in contentious times.

| A guide to U.S. Politics |

| Hail to the Chief? |

| Persons of interest |

|

v - t - e |

Background

One of the few presidents to have been born into poverty, he eventually rose up to become an attorney.[1] He was elected to the House of Representatives in New York's 32nd district in 1832 as a member of the Anti-Masonic Party, and he would later join the Whigs when they formed. He was a "moderate" when it came to slavery; he opposed the practice, but felt the federal government had no right to interfere with the states' rights to have slaves. After being defeated in bids to become Speaker of the House in 1841, Vice President in 1844, and Governor of New York also in 1844, his big break would come in 1848, when he would be chosen as Vice President to Zachary Taylor. He was chosen to balance the ticket as a northerner, since Taylor was a southerner who owned many slaves. They didn't get along too well; Fillmore would focus on presiding over the Senate rather than working together on policy, and Fillmore would fire the entirety of Taylor's cabinet upon taking office. Their main disagreement was on the group of bills which would become the Compromise of 1850 (see below), which Fillmore supported and Taylor did not, but when Taylor died unexpectedly in 1850, Fillmore would get the presidency.

Compromise of 1850

His most notable achievement as President was to pass the Compromise of 1850, which were five bills written by Whig Senator Henry Clay and Democratic Senator Stephen Douglass (who is most famous for his later presidential run against Abraham Lincoln). It was written to finally for once and for all settle the question about whether to expand slavery in the territories, after the previous attempt (Missouri Compromise of 1820) didn't work out too well. Basically, after the Mexican-American War, the U.S. found itself with a lot of new territory, and while Southerners were excited about the prospect of expanding slavery to the new territories, none of the land was good for growing crops like tobacco and cotton that slave labor made extremely profitable. This came to a head when California wanted to become a state - at the time, there were an equal number of slave and free states, and California didn't want to allow slavery, meaning adding it would throw off the balance. The compromise added California as a free state, as well as banning the slave trade in DC. However, the remaining territories from the Mexican Cession would have popular sovereignty, meaning the people of the territories would vote on whether or not to allow slavery. Most infamously, the Compromise included the Fugitive Slave Act, which required government officials and even ordinary citizens in free states to assist in catching escaped slaves, which helped turn many northerners against the practice. So basically, southerners were pissed off because they had become the minority in Senate, northerners were pissed off because they had to support slavery when many could previously look the other way, and the fate of New Mexicans and Utahns still wasn't settled.[1]

Foreign policy

His other major achievement besides the Compromise of 1850 was the Perry Expedition

Cuba was another major foreign policy issue at the time. Since many southerners knew that it would be an uphill battle to have slavery in the areas granted by the Mexican cession due to the climate there making plantations unprofitable, many wanted to instead expand to the Caribbean and Central America in order to add new slave states (see the Golden Circle

Post-presidency

By the end of his presidency, Fillmore was unpopular and especially hated in the north for his enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act, however, he still had some support in the south for those who felt he was a "compromise candidate". Fillmore at first was fine with stepping down, as he wanted his friend Daniel Webster

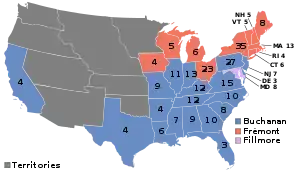

Shortly after he left office, tragedy struck, with his wife dying of pneumonia. He alongside many of the southern Whigs ended up joining the nativist Know Nothing Party. Fillmore would receive their nomination in 1856. He rarely spoke about immigration, which was ostensibly the main position of the Know Nothings, but rather talked about preserving the union. He essentially ran as a compromise candidate again, as he wanted to leave the expansion of slavery into the territories open, unlike the Republican nominee John C. Frémont

It's kind of sad; despite wanting his country to be united, his actions led to the fracturing of his party and the resulting elections of two of the worst presidents of all time and ultimately the bloodiest conflict America has ever been in.

External links

References

- Michael Holt, Millard Fillmore: Life in Brief, UVA Miller Center

- Michael Holt, Millard Fillmore: Foreign Affairs, UVA Miller Center

- Presidential Election of 1852: A Resource Guide, Library of Congress

- Presidential Election of 1856: A Resource Guide, Library of Congress