The Great Video Game Crash of 1983

In the early 1980s, the American video game industry was in its second generation and making money hand over fist. Arcades were popping up across the country like daisies, the Atari 2600 dominated its competitors in the home market, and no-relation-to-the-trope Pac-Man Fever held the nation in its iron grip.

In 1983, however, something went terribly wrong. Dozens of game manufacturers and console producers went out of business, production of new games crawled to a standstill, and the American console game market as a whole was dead for the next two years. What happened? Although the Crash was an industry-wide phenomenon, the best place to start is with the downfall of Atari, a tale forever linked to the Crash:

- Atari's principal hardware platform, the model 2600 game console, was showing its age technologically. Designed in 1977 to be manufactured cheaply, its graphics were primitive and its memory severely limited (128 bytes - not kilobytes or megabytes - of RAM). The limitations were initially tolerated as the common mass-market computers in 1977 were the then-new Apple ][ (powerful but expensive), Commodore PET (no colour graphics) and Radio Shack "TRaSh-80" (no colour or sound). By 1983? Desktop computers were coming down in price, their sound and graphics were improving and consumers were looking for a system which could do more than just play a few primitive video games.

- Atari refused to give game designers authorial credit or royalties. Many of Atari's programmers left to form their own companies to make games for the 2600, the most famous and successful of which is Activision. Atari lost its legal attempts to prevent this, which allowed the most creative people in the industry to directly compete with Atari's own efforts.

- Atari's business strategy — sell its consoles as cheaply as possible while relying on game sales for profit — made the situation worse. It worked when Atari was the only game in town, but with the rise of the competition, Atari's profits suffered.

- Atari was responsible for a number of notoriously poor high-profile games in late 1982. The most notable were a designed-in-six-weeks version of Pac-Man and an awful adaptation of ET the Extra Terrestrial, which are widely panned as two of the worst games ever made. Not only were these and similar games awful, but Atari over-produced them — 12,000,000 copies of Pac-Man were made for a 10,000,000-console industry in the hopes it would be a system-seller. Angered stores returned the unsellable products in droves. When the company was left with millions of dollars in worthless cartridges, it dumped them in a landfill in the New Mexico desert.

- The closest thing the Crash had to a "Black Tuesday" was December 7, 1982. During a shareholder meeting, Atari reported a 10-15% expected increase in profits. This doesn't sound too bad, but was far below the 50% increase people had expected. By the next day, the stock of Warner Communications, Atari's parent company, immediately dropped 33%, and a mini-scandal erupted when it was revealed that the president of Atari, Ray Kasser, had sold 5,000 shares of the company half an hour before making his announcement.

With its customer base eroded, Atari had racked up nearly half a billion (and that's not adjusting for inflation) in losses by the end of 1983. Atari wasn't alone in its troubles, as its competitors were also facing hard times:

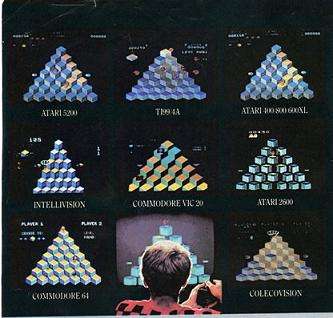

- A glut of companies attempting to follow in Atari's success gave consumers too many choices, which meant no one system could succeed in the long term, since very few consumers would buy more than one. These included (but were not limited to) the Bally Astrocade, the ColecoVision, the Coleco Gemini (a 2600 clone), the Emerson Arcadia 2001, the Magnavox Odyssey Odyssey², the Mattel Intellivision, the Vectrex, and the Fairchild Channel F-System II.

- A similar problem occurred with software. Games for these systems were cheap to produce, and since their makers figured they'd sell no matter the quality, poor titles from dozens of hastily-created start-ups flooded the market.

- As game developers went out of business, retailers were left with unsold product that could not be returned. Hoping to salvage something, stores offered massive discounts just to clear inventory. The market for higher-priced new games shrunk in the face of large amounts of budget-priced crud, especially since...

- It was hard for consumers to tell the good games from the bad. The Internet was unavailable to the general public and magazines and books had a long lead time and could only review a few games, so most buyers were left with only the screenshots and text on the back of the box. Since these were usually nonsense designed to sell the game, consumers were left once-bitten twice-shy.

- The home computer market made its first competitively-priced entry into American society. Though computers had software libraries which catered to the early gaming crowd, their educational and office software gave them an edge. Certain computers, such as the Commodore 64, were also priced and marketed to compete directly with game consoles.

- A media backlash, viewing video games as a fad, played up the various company bankruptcies as proof the industry was dying.

The Crash killed the American home console market for two years — video game sales dropped from $3 billion in 1982 to as low as $100,000,000 in 1985, and many game companies went out of business.

When it was revived, it was done from the outside: via the introduction (and overwhelming success) of the Nintendo Entertainment System. As a result, Japan replaced the USA in dominating the home market. This was particularly evident in the case of Sega, whose American parent company, Gulf & Western, sold it to a Japanese corporation in 1984, minus its former U.S. division.

The Crash was a uniquely American phenomenon, and even there, it never risked killing video games as a medium. The rise of the home computer (particularly the Commodore 64) continued home video gaming, and while the American arcade scene was beginning its slow decline, arcade games were still near the height of their popularity. Minor arcade classics like Paper Boy, Punch-Out!!, Space Ace, Karate Champ, and Gauntlet (1985 video game) found their release during this period. Many of these arcade games would later be ported to home consoles (with varying degrees of success) after the market was revived — but we're getting ahead of ourselves.

Across The Pond, the European market was dominated by early home microcomputers (predominantly the Sinclair ZX Spectrum and [again] the C64), with an outrageous number of one-person coders writing games for the far-cheaper tape distribution system. These machines became the backbone of the industry for the next decade; the so-called "bedroom coders" would receive status ranging from "cult hero" (Jeff Minter, Matthew Smith et al) to "legend" (Bell and Braben, the Oliver Twins). That didn't prevent some quite talented developers from making enough stupid decisions to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory, of course (Imagine Software, most notably; see here for info, with a big example of an Orwellian Editor as a bonus). Even with the missteps, the European gaming industry remained solid.

The Crash also did not affect Japan. Though the home of a massive arcade base that naturally grew from Pachinko Parlors and Mah Jongg dens, Japan was not a particularly early adopter of home systems, and most American imports were curiosities at best. Japan received the Famicom console and the MSX computer in 1983, right after the crash in America. Those two systems would dominate the Japanese gaming industry for the rest of the decade. Interestingly, near the start of '83, Atari had started negotiating the rights to the Famicom's U.S. release, though this would eventually be scuttled by the effects of the Crash. But oh, What Could Have Been...

Deciding to go it alone, Nintendo launched the Famicom two years later in the States as the Nintendo Entertainment System, and was able to achieve near-monopoly status. Nintendo's Seal Of Quality system, coupled with a cartridge design that couldn't be manufactured without Nintendo's approval, provided some protection against the low-quality shovelware which had plagued the Atari. To assuage the concerns of American shopkeepers uneasy about stocking a new video game system, the NES was designed with a front-loading cartridge slot to make it look more like a VCR than a game console. It was also bundled with the Robot Operating Buddy and Zapper peripherals, which looked much more like conventional toys.

Very few toy stores were fooled, but success in test markets and a brilliant advertising strategy landed the NES space on store shelves across the country. And the NES had the perfect game to bundle for the 1985 U.S. release, about a fat Italian plumber, best known for antagonizing a giant monkey, who ventured across a land overrun by turtles and walking mushrooms in order to save a princess from the grasp of a dragon-turtle villain.

It was just Crazy Enough to Work.