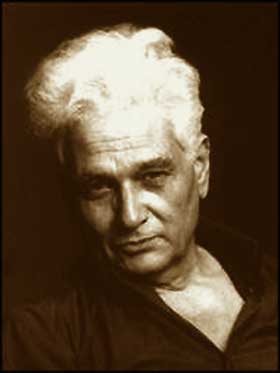

Jacques Derrida

"Every discourse, even a poetic or oracular sentence, carries with it a system of rules for producing analogous things and thus an outline of methodology."

Jacques Derrida (July 15, 1930 – October 9, 2004), was a Jewish Frenchman born in Algeria who popularised the term Deconstruction. Amusingly enough he was originally named "Jackie" after the famous actor Jackie Coogan, but changed it to the more proper Jacques when he moved to France. World War Two broke out when he was a boy in France he was kicked out of school (along with every other person of Jewish background) as per the orders of the Nazi puppet regime set up in France after their surrender. Instead of going to the schools for displaced Jews, Derrida skipped school for a while and actually got involved in soccer, hoping to turn pro. He took an interest in philosophy around this time, which took him down a very different career path.

Following the end of the Second World War, Derrida went to study philosophy at the the prestigious École Normale Supérieure and Harvard a few years later. His first published work was a translation of Husserl's Origin of Geometry, complete with Derrida's own introduction, which impressed the French academic establishment and won the Jean Cavaillès prize. In 1964 he returned to Normale, this time as a teacher. Derrida got the attention of the international community with his writing, "Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences", an essay on structuralism, and subsequently began publishing other works, including Of Grammatology, which would be part of the basis for his concept of Deconstruction. He was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Derrida was found to have pancreatic cancer in 2003 and died in 2004.

Derrida introduced the term "deconstruction" in Of Grammatology. In literary criticism, the word is sometimes loosely defined as "reading against the grain" - the practice of looking for ways in which a text can be read as contradicting or questioning itself. Conventionally, the text is said to have deconstructed itself, because the ambiguities were already there before the critic pointed them out to you, whether you noticed them or not. This approach is associated with a group of literary critics called the Yale School. However, like most of Derrida's coinages, his use of the word is subversive, fluid and notoriously hard to define. Derrida did not regard deconstruction as a concept or a method, preferring to let his readers infer a meaning from it. This way, it retains its ambiguity and cannot be co-opted by any kind of establishment.

Derrida's style is pretty unusual, and can initially seem very confusing. This is because he deliberately avoided most philosophical conventions like arguing and advancing points, instead exploring different existing ideas and works and seeking to destabilise their foundations. This way, he would uncover new ways to view and intepret these texts. He was especially distrustful of boundaries and binary oppositions such as male/female, inside/outside, speaking/writing and so on, and so he would identify areas of undecidability, which would upset these distinctions. To use one of Derrida's own examples, a virus throws the distinction between a living thing and an inanimate object into question; it cannot be accurately classified as either, but it has the characteristics of both. Derrida identifies similar undecidabilities throughout his work. He sought to show that meaning was not fixed by incorporating puns and word games, including passages which are deliberately difficult to translate, phrases which mean totally different things when taken out of context, and words with no specific meaning but which hint at other words. He was also influenced by many writers from outside the philosophical tradition, often modernist writers like James Joyce, Stephane Mallarme and Franz Kafka.

Naturally, a lot of people found all of this really annoying. Always a controversial figure, Derrida has often been accused of being trivial or needlessly confusing, but remains highly influential within the arts and humanities.

- Genre Busting: to the point where even the question of whether to call him a philosopher or a critic is disputed.

- Pastiche: Ulysses Gramophone is written to resemble literary fiction, especially Joyce's Ulysses.

- Unconventional Formatting: the essay Glas, to the point where some critics consider it a work of modern art.