Closed Captioning

Closed captions, also known as subtitles, were introduced in the 1970s by The BBC for the benefit of hearing-impaired TV viewers. In the United States, deaf viewers were served until 1980 by onscreen sign interpreters, at least on South Dakota's CBS affiliate, KELO-TV, and its satellite stations. Main Street Living still uses sign language interpreters, along with "Mass for Shut-Ins" programs, which retain that form both for familiarity for older viewers (who may find captions distracting or hard to get on newer televisions) and for cost concerns as it is less expensive for a church organization to hire an interpreter to sign a service than hire a transcriber to caption it. The BBC continues to air some repeats with an onscreen sign-language interpreter in the early hours, presumably as a teaching aid for people wishing to learn British Sign Language, and also a magazine show aimed specifically at deaf people called See Hear. See Hear is noteworthy for having subtitles for the benefit of viewers without hearing impairment.

Closed captions are so called because they can be displayed or hidden as the viewer wishes. Captioners try to place captions so as not to cover an important part of the picture, such as the name of an interviewee on a news program, but that isn't always possible. Open captions also exist, but are seldom used. They can be created with a character generator or inserted right into the program itself rather than embedded in the video signal.

The reason for this is simple. Prior to the FCC mandating virtually all television sets have closed captioning included, the only way to receive captioning was an expensive (about the same cost as a television set) closed captioning set-top box. So to allow deaf people who might not be able to afford a captioning box, a number of programs were open captioned. Once close captioning became possible to be received by almost every TV set in the United States, open captioning was no longer necessary as almost any TV now has closed captioning built-in. About the only place where open captioning is still used is when someone's speech is considered very poor or hard to understand, so their words will be open captioned.

Transcribers of closed captioning go through the same process of career training as court reporters and type on the same type of machine modified for television use, called a stenotype machine. This is because court reporters are by training meant to transcribe words as fast as possible without any pause, which is very important for live television broadcasts as a typist trained on a traditional QWERTY keyboard layout is limited by the intentional hamstrings of QWERTY (which was designed in the 1870s to slow down typists from jamming typewriter keys and has been retained to the current day to much consternation; only the most elite of QWERTY typists can keep up with court reporters). As both the law and people with hearing disabilities will always exist, court reporters are usually guaranteed a good job with great perks (such as the ability to usually be the first in the nation to watch a completed TV episode), though they have heavy financial and job security penalties intentionally written into their contracts to prevent any form of Spoiler leakage. Almost all pre-recorded programming except for long cancelled archived programming is captioned on-site at the studio or a captioning organization's offices due to the risks of an episode being leaked, while live events such as news and sports can be captioned at home by telecommuting transcribers who watch the program live and caption on the fly.

Captions tend to be in all uppercase because early decoders couldn't display lowercase letters with true descenders (i.e. the tails of lower-case letters like G, J, P, Q and Y which go below the letters). Before TV sets had built-in decoding circuitry, a viewer needing the capability could buy an (expensive) external decoder, similar to the (not too expensive) external decoder used to allow an analog TV to receive digital over-the-air broadcasts. All TV sets made in the United States over 13 inches diagonally since July 1993 have had the decoders built in (though digital portable sets under 13 inches also include caption chips).

Television programs are virtually 100% captioned because the FCC has put a requirement on virtually all television program producers to do so. Basically the only exceptions are producers with revenues of less than US$3 million a year, but even then when you're trying to get your program viewed by as many as possible, captioning is a must, making local cable access channels the de facto only organizations to not use them.

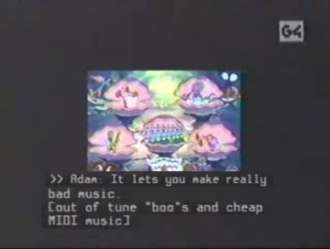

There are three main kinds of closed captions: roll-up or scrolling, used for news programs and other live broadcasts, as well as for The Price Is Right; pop-on, pop-up, or block, used for fully scripted programs; and paint-on, used mainly for commercials and special effects. Roll-up captions are done live and can lead to some funny errors.[1] Every once in a while the script used for captioning is an older version, or does not exist at all, causing the captioning to not totally match the spoken dialogue. Also, enhanced computer power has allowed for the development of speech-to-text software, and sometimes the computer-generated captions use the wrong word, especially for homophones; e.g., a military program using the word "ordnance" (weapons) might display the word "ordinance" (a local law). As seen above, it's very rare for a closed captioning transcriber to play the role of a Hidden Track Deadpan Snarker or MST'er unless a show asks him to be, so usually captions are modified directly from the shooting scripts with only minor formatting to show the transcriber as a True Neutral viewer of the program who couldn't care less about who is sleeping with whom.

Some programs, such as Survivor, are captioned in the roll-up live style specifically to prevent spoiler leakage. In the particular case of South Park, the program is often finished only hours before first airing, making a traditional pop-on session immediately impossible (the pop-on session takes place after airing and that style will be seen in weekend encores of a new episode).

Also, when closed captions are displayed for works aired on TV which censor a word but not a whole sentence, they often display the censored word anyway. Sometimes they'll only censor part of the word; e.g., if the word "asshole" is used, it will be displayed as "ass[censored]" while the word itself is completely bleeped out. The reverse can even occur, such as in Crank Yankers, which sometimes censors even innocuous words when they are uncensored on the show.

Sometimes captions will give information that you do not get if you're hearing the show. In some cases, captions will identify people (especially when they are speaking with their face away from the camera), give dialog that is spoken too softly to be heard, or mention things not necessarily apparent (especially if the program was captioned from the script rather than the actual performance, which may have had parts of the script dropped).

Local news depends on the budget of the station; if they can afford it, "real time" captions display and a transcriber at the station or watching by satellite can transcribe the newscast. Lower-tier stations will plug in the unedited raw script and roll that instead, which means viewers get to wonder what "NAT" (a scene with natural background noise) is, and wonder why the weather forecast is never captioned (mainly because meteorologists usually ad-lib rather than script out their forecast).

In the American/Canadian standard there are also four closed captioning "channels" available, which allows for secondary captions in different languages (usually Spanish in the United States, or English on the Spanish networks such as Univision and Telemundo, and French in Canada); these are usually seen on the "CC3" caption channel.

Currently, captioning is less regulated when it comes to Internet programming sources. Hulu and iTunes usually have most of their programs captioned, but Netflix and the video players of many television networks often are not, and the menus to open the captions up are often buried.

Closed captions, while not standardized, have their own conventions:

- Narration is usually italicized. In Canadian closed captioning, brand names are as well.

- A change of speaker is usually indicated by either two or three greater-than (>) symbols, or by the new speaker's name (especially if the speaker can't be seen speaking). This is usually used on roll-up captions.

- On pop-on captions, hyphens (-) are often used to denote multiple speakers.

- Captions display not only dialog, but also how the dialog is spoken, as well as descriptions of music and other sound effects.

- Some Twentieth Century Fox movies have their opening logo (the stacked "20th Century Fox" with searchlights) captioned, in which the captioning reads "[LIVELY FANFARE]" "[FANFARE CONTINUES]" then with the last four notes, "[FANFARE ENDS]".

- Song lyrics are delimited by single eighth notes (♪). The last line is followed by a pair of eighth notes (♪♪).

- Almost all captioning is white-on-black and uses sans-serif fonts. Occasionally, rare usage will appear with text in green, yellow, red or cyan instead of white. This is limited only to music videos and "this program was captioned by" plugs.

- However, any user with an HDTV is able to change color, font type and background to meet their own needs, so the viewer can watch a program with all dark red captions in Comic Sans with a white background and deep text shadowing. Unless you're a sadist, however, that isn't advised.

- Closed-captioned dialogue is often simplified on children's programs, such as Sesame Street, obviously to make it easier for the hearing-impaired division of its target audience to follow.

- The first seven seasons of Arthur were like this too; but the CC1 track contained the regular captions (which used to use all-capital letters for dialogue prior to 2000, when they were then redone in all-lowercase), while the CC2 track contained simplified captions (this would also describe certain things, like the vibraphone transition sound effects described as ([name of character] is imagining), ([name of character] stops imagining), etc. )

- Word puns are often pointed out to the viewer, since a deaf person, having never heard the sounds of the words, might not otherwise pick up on double meanings.

- The American closed caption signal can be recorded off-air onto videocassettes. Likewise, closed captioning can be included on pre-recorded tapes, or on DVDs as an alternative to regular DVD subtitling. HDMI, however, doesn't pass through captions, so in that case captions have to be set up via the viewer's form of set-top box to be viewable, while Blu-Ray discs must be viewed with studio subtitles rather than captions.

The more powerful Ceefax teletext system used by British subtitlers allows them an even more complete set of conventions, codified by Ofcom:

- Speech rotates among white-on-black, yellow-on-black, cyan-on-black and green-on-black. Main characters may get one devoted to them for the entire show while more minor ones get whatever is available.

- Non-human voices (e.g. those of robots or monsters) get white-on-blue.

- Sound effects are white-on-red in all-caps.

- Song lyrics are delimited by # signs, with an extra # at the end of the last line.

- Sarcasm is denoted with (!), unlike the American/Canadian style where it's just described as being sarcastic.

Unlike U.S. closed captioning, the analogue teletext signal in Britain can not be recorded on home video.

The American caption system also had a Ceefax-like "text channel" built into the standard which was used to deliver news, sports scores and program schedules. Only ABC and TBS really embraced it, however, and now the text channel remains solely as a never-used Artifact.

WGBH's CC FAQ has more information. See also the Wikipedia article on closed captioning.

For the equivalent aid for the visually impaired, see Audio Description.

- ↑ Whenever a captionist comes across an incoherent or unfamiliar word, they must quickly provide one as close to the dialogue as they can to keep up with the speech, no matter how ridiculous it may sound.