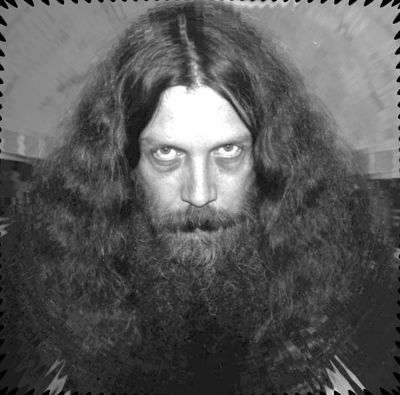

Alan Moore

"Life isn't divided into genres. It's a horrifying, romantic, tragic, comical, science-fiction cowboy detective novel. You know, with a bit of pornography if you're lucky."—Alan Moore

Alan Moore knows the score.—Pop Will Eat Itself

Probably the most widely recognised (and arguably insane, although in that nifty-creative Howard Hughes and Orson Welles way) Comic Book writer of all time, Alan Moore was born in Northampton, England, and got his start writing and drawing cartoon strips for music magazines such as The NME. He moved on to get regular work at Marvel UK, where he wrote the Captain Britain comic, and Two Thousand AD, where he wrote a series of acclaimed stories, including DR and Quinch and The Ballad of Halo Jones. This period included V for Vendetta, about an anarchist planning to take down a fascist UK Government, and Miracleman, a reinvention of a 1950s British superhero.

Moore was then encouraged by DC Comics editor Len Wein to start work on Swamp Thing, Wein's classic horror comic. Originally about a scientist, Alec Holland, who had been transformed into a living plant monster after an explosion in his lab, Moore proposed a radical revision that revealed that Alec had in fact died in the explosion, and that the swamp creature had been created by plant elementals using Holland's memories as a basis for its character. Swamp Thing was not a man turned into a monster; he was never a man at all! Moore then took the Swamp Thing through a number of unusual adventures, including an entire issue dedicated to psychic, psychedelic sex between Swampy and his human girlfriend, Abby. Moore also created the character of John Constantine for the comic. Along the way, he wrote a tiny handful of Superman stories which are now considered some of the very greatest ever written for the character (one was even adapted into an episode of Justice League Unlimited) and set the groundwork for a more extensive examination of Superman later in his career, through the pastiche character Supreme. Not to mention a tiny handful of Green Lantern stories that have become integral to its history ("Mogo Doesn't Socialize" and "Tygers").

Swamp Thing proved to be a massive success, and in the last years of Moore's run on the title, he was also handed another gaggle of existing characters to play with. DC had recently acquired the properties of Charlton Comics and Moore was asked to come up with a proposal for them. He came back with a dark tale that drew heavily on the mid-80s Cold War angst, in which the Charlton heroes discover that one of their number has been killed and that his death is connected to something that could lead to nuclear armageddon. DC was impressed by the pitch but was worried that Moore's pitch would render a number of the characters unusable by the end of the story. Instead, they advised him to create an entirely new series, and so Watchmen was born. Mature beyond anything that mainstream comics had published up to that point and with a level of complexity that rivaled the most highbrow books of the time (and continues to rival the best that many writers can come up with), Watchmen proved to be a massive sensation, and with Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns, effectively launched the Dark Age of comics. (Moore's Batman one-shot The Killing Joke in 1988 was another big success in this regard—its approach to the Joker became the Trope Namer for Multiple Choice Past.) It also contributed heavily to the growing realisation in the mainstream media that comics are an art form, along with other comics such as Art Spiegelman's Maus and Gilbert and Jamie Hernandez's Love and Rockets.

Ironically, the popularity of Watchmen was the first nail in Moore's relationship with DC; the contract that he and artist David Gibbons had signed promised them that full rights to the comic would be returned to them if the book fell out of print for more than two years. At this point in time, paperback collections of comic books were virtually unheard of and the idea that Watchmen would remain in print that long was absurd. However, the book's popularity kept it in print from 1987 through to the present day, and neither Moore nor Gibbons ever received the rights. Moore's relationship with Marvel Comics was also strained, and for similar reasons.

After Watchmen, Moore moved into independent comics, writing Brought To Light, a history of the CIA; Lost Girls, a piece of highbrow erotica; and A Small Killing, the story of a graphic designer who finds himself stalked by a strange little boy. In the mid-90s, he also began doing more work-for-hire writing for companies such as Wildstorm Comics and Image Comics. Through Wildstorm, he published his own imprint, America's Best Comics (ABC), which included Promethea, a 32-issue treatise on magic (Moore has been a practicing magus since his 40th birthday); Top Ten, a pastiche of Police Procedural TV series set in a superhero-populated city; and Tom Strong, a call back to a more innocent era of comic writing. Perhaps the best-known ABC comic, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, is a Victorian-era set superhero story set in a universe in which all stories exist alongside one another. Thus, the titular team comprises Mina Murray (Mina Harker of Dracula, reverting back to her maiden name), Allen Quatermain (King Solomons Mines), Captain Nemo (20,000 Leagues Under the Sea), Hawley Griffin (The Invisible Man) and Dr. Jekyll/Mister Hyde (duh).

However, Wildstorm was bought out by DC Comics and Moore subsequently parted from America's Best Comics. As of 2008, the only title he plans to write with any regularity is The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, which after The Black Dossier, will be published through Top Shelf Productions. He is also currently working on his second prose novel, tentatively titled Jerusalem.

Apparently, his amazing talent comes from Satan. Not by selling his soul for it, mind you, but because he used to beat Satan up for his lunch money until the Devil bribed Moore with genius to leave him alone. Additionally, Death is afraid of him.

He is known, with a particularly vivid description of From Hell, to have driven Neil "Scary Trousers" Gaiman to leave a restaurant to go outside and get some fresh air so he wouldn't vomit. Twice. Gaiman also wrote this short comic about him, which pretty much sums up how many people view him.

Is famous for hating any and all adaptations of his work simply for being adaptations of his work, citing that he writes comics and thus that any adaptation of a comic written by him that is not a comic written by him is wrong. This is in spite of the fact that practically everything he's ever written has been an adaptation of someone else's work or using someone else's characters.

Did we mention he's also polyamorous, vegetarian, anarchist and an accomplished chaos mage?

Sometimes goes by the name of Translucia Baboon to warn us all about ducks. Is the quintessential modern Mad Artist.

- Appeal to Audacity: Whether done deliberate by Moore is open to debate, this is one of the cornerstones of his works by his fans.

- Makes Just as Much Sense in Context: Vary from work to work but more than one fan can describe him like this.

- Magic, especially as a supernatural expression of information

- Anarchy as a positive force. He's actually quite proud of the Guy Fawkes mask becoming a symbol.

- Wordplay (and imageplay)

- Synchronicity

- Making heavy use of the Match Cut technique to present a united narrative.

- The effect of the presence of superheroes or the supernatural on "real world" culture and society. This involves averting Reed Richards Is Useless and Cut Lex Luthor a Check.

- Reinvention of existing characters

- Mixing fiction and historical fact

- Drugs are great! His works often feature characters using hallucinogens to positive effect, such as Ozymandias in Watchmen and the cop in V for Vendetta. Also, when Miracleman changes the world, he legalises all drugs.

- Lots of sex. Lost Girls and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: The Black Dossier stand out.

- He also has a thing for Rape as Drama. However, it is almost always done tactfully. But some scenes in his current Neonomicon project take explicit rape to Nausea Fuel lengths.

- Darker and Edgier: Along with Miller's The Dark Knight Returns, Moore's earlier works have been credited with leading the trend. Note that his works, while often dark, are almost always idealistic, and his later works were often lighter (while always retaining an edge).

- Surreal Horror: Several of his lates works contain heavy dosis of this.

- Deconstruction, especially in the form of Deconstruction Crossover. Actually, Moore probably codified the latter trope with his graphic novel series The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen.

- Reconstruction, especially considering how some of his more famous deconstructive works ushered in the Dark Age. His works such as 1963, his runs on Supreme and Youngblood as well as Tom Strong are clear examples.

- Experimentation with form: symmetrical and chiastic story structures (e.g. the pirate comics in Watchmen), playing with the chronological order of events (the fourth chapter of Watchmen, which jumps back and forth between the past, present, and future), as well as layouts enabling dialogue to be read in different orders (e.g. the Mobius strip segment in Promethea).

- Disinterest in movie adaptations of his work and Hollywood in general.

- However, he did like the JLU adaptation of his Superman story "For the Man Who Has Everything". This was possibly because they weren't his characters, and the producers bothered to ask him first. Notably, his name actually appears in the credits for the episode.

- He's also stated explicitly that he does not think as poorly of them as he is generally reputed to. Generally, his opinion is more along the lines that his works are made specifically to be comic books, and will not hold up in transition.

- Freemasonry, often with ominous, but not supernatural, undertones.

- And, of course, Doing It for the Art. He never does it for anything else.

- Black Comedy and Kafka Komedy: A lot of his work from his early days at Two Thousand AD is overflowing with this (especially DR & Quinch and his collection of Tharg's Future Shocks). These themes remain in his later works, but they are not nearly as prevalent as they are in some of his oldest stories.

- Humans Are Flawed / Crapsack World: Every major character in his stories will always be guaranteed to have some kind of obvious flaw or otherwise unlikable trait, a variant of Humans Are the Real Monsters and Humans Are Morons perhaps being the two most common (but certainly not the only ones), while the city/world/universe his stories take place in are very grim and despairing places; no one ever really has much hope for anything in Moore's stories, let alone hope for their own personal ambitions or goals in the story (even if the story concludes with a genuinely happy ending).

- Along with this, Black and Grey Morality is pretty much a given.

- Idiosyncratic Episode Naming: Chapter titles in his individual works occasionally follow a common theme. For example, V for Vendetta and words that begin with the letter V, Watchmen and its Literary Allusion Titles, DR & Quinch and titling each separate story "DR & Quinch _______" and so forth..

- Alternate Company Equivalent and Expy characters abound in many of his works.

- Rape as Drama: Is it an Alan Moore work? Has anybody been raped yet? If the answer to the first question is yes and the answer to the second question is no, the proper response is "Wait for it."

Selected bibliography:

- Miracleman (AKA Marvelman; 1982-1984)

- V for Vendetta (1982-1988)

- DR and Quinch (1983-1985)

- The Ballad of Halo Jones (1984-1986)

- Swamp Thing (1984-1987)

- For the Man Who Has Everything (1985)

- Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? (1986)

- Watchmen (1986-1987)

- The Killing Joke (1988)

- From Hell (1991-1996)

- Lost Girls (1991-2006)

- 1963 (1993)

- Voice of the Fire (novel; 1996)

- Youngblood Judgment Day (1997)

- Supreme (1997-1998)

- Top Ten and various spin offs (1999-2001)

- Tom Strong (1999-2006)

- Promethea (1999-2005)

- The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (1999–present)