Grapefruit

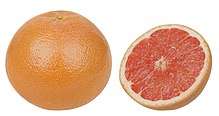

The grapefruit (Citrus × paradisi) is a subtropical citrus tree known for its relatively large sour to semisweet, somewhat bitter fruit.[1] Grapefruit is a citrus hybrid originating in Barbados as an accidental cross between the sweet orange (C. sinensis) and pomelo (or shaddock; C. maxima), both of which were introduced from Asia in the 17th century.[2] When found, it was nicknamed the "forbidden fruit".[1] Frequently, it is misidentified as the very similar parent species, pomelo.[3]

| Grapefruit | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pink grapefruit | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Rutaceae |

| Genus: | Citrus |

| Species: | C. × paradisi |

| Binomial name | |

| Citrus × paradisi Macfad. | |

The "grape" part of the name alludes to clusters of fruit on the tree that often appear similar to grape clusters.[4] The interior flesh is segmented and varies in color from white to yellow to pink to red.

Description

The evergreen grapefruit trees usually grow to around 5–6 m (16–20 ft) tall, although they may reach 13–15 m (43–49 ft).[1] The leaves are glossy, dark green, long (up to 15 cm (5.9 in)), and thin. It produces 5 cm (2 in) white four-petaled flowers. The fruit is yellow-orange skinned and generally, an oblate spheroid in shape; it ranges in diameter from 10 to 15 cm (3.9 to 5.9 in). The flesh is segmented and acidic, varying in color depending on the cultivars, which include white, pink, and red pulps of varying sweetness (generally, the redder varieties are the sweetest).[1] The 1929 U.S. Ruby Red[1] (of the 'Redblush' variety) has the first grapefruit patent.[5]

History

The genetic origin of the grapefruit is a hybrid mix.[6] One ancestor of the grapefruit was the Jamaican sweet orange (Citrus sinensis), itself an ancient hybrid of Asian origin; the other was the Indonesian pomelo (C. maxima).[1] One story of the fruit's origin is that a certain "Captain Shaddock"[1][7] brought pomelo seeds to Jamaica and bred the first fruit,[8] although it probably originated as a naturally occurring hybrid between the two plants some time after they had been introduced there.[1][2]

The Trunk, Leaves, and Flowers of this Tree, very much resemble

those of the Orange-tree.

The Fruit, when ripe, is something longer and larger than the largest

Orange; and exceeds, in the Delicacy of its Taste, the Fruit of every

Tree in this or any of our neighbouring Islands.

It hath somewhat of the Taste of a Shaddock; but far exceeds that, as

well as the best Orange, in its delicious Taste and Flavour.

—Description from Hughes' 1750 Natural History of Barbados

The hybrid fruit, then called "the forbidden fruit", was first documented in 1750 by a Welshman, Rev. Griffith Hughes, who described specimens from Barbados in The Natural History of Barbados.[1][9][10] Currently, the grapefruit is said to be one of the "Seven Wonders of Barbados".[11]

The grapefruit was brought to Florida by Count Odet Philippe in 1823, in what is now known as Safety Harbor.[1] Further crosses have produced the tangelo (1905), the Minneola tangelo (1931), and the oroblanco (1984).

The grapefruit was known as the shaddock or shattuck until the 19th century.[1][7] Its current name alludes to clusters of the fruit on the tree, which often appear similar to those of grapes.[4] Botanically, it was not distinguished from the pomelo until the 1830s, when it was given the name Citrus paradisi. Its true origins were not determined until the 1940s. This led to the official name being altered to Citrus × paradisi, the "×" identifying its hybrid origin.[12][13]

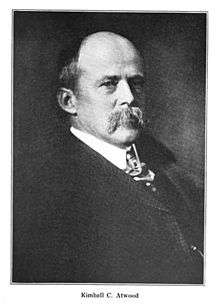

An early pioneer in the American citrus industry was Kimball Atwood, a wealthy entrepreneur who founded the Atwood Grapefruit Company in the late 19th century. The Atwood Grove became the largest grapefruit grove in the world, with a yearly output of 80,000 boxes of fruit.[14] There, pink grapefruit was first discovered in 1906.[15]

Ruby Red

_white_bg.jpg)

The 1929 Ruby Red (or 'Redblush') patent was associated with real commercial success, which came after the discovery of a red grapefruit growing on a pink variety.[1] Using radiation to trigger mutations, new varieties were developed to retain the red tones that typically faded to pink.[16] The 'Rio Red' variety is 2007 Texas grapefruit with registered trademarks Rio Star and Ruby-Sweet, also sometimes promoted as Reddest and Texas Choice. The 'Rio Red' is a mutation-bred variety that was developed by treatment of bud sticks with thermal neutrons. Its improved attributes of mutant variety are fruit and juice color, deeper red, and wide adaptation.[17]

'Star Ruby'

The 'Star Ruby' is the darkest of the red varieties.[1] Developed from an irradiated 'Hudson' grapefruit,[18] it has found limited commercial success because it is more difficult to grow than other varieties.[19][20]

Varieties

The varieties of Texas and Florida grapefruit include: 'Oro Blanco', 'Ruby Red', 'Pink', 'Rio Star', 'Thompson', 'White Marsh', 'Flame', 'Star Ruby', 'Duncan', and 'Pummelo HB'.[21]

Production

In 2018, world production of grapefruits (combined with pomelos) was 9.4 million tonnes, led by China with 53% of the world total. Secondary producers were Vietnam and the United States.[22]

| Grapefruit production in 2018 | |

|---|---|

| Country | Production (millions of tonnes) |

| Source: FAOSTAT of the United Nations[22] | |

Colors and flavors

Grapefruit varieties are differentiated by the flesh color of fruit they produce. Common varieties are red, white, and pink pulp colors. Flavors range from highly acidic and somewhat sour to sweet and tart, resulting from composition of sugars (mainly sucrose), organic acids (mainly citric acid), and monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes providing aromas.[23]

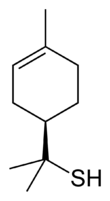

Grapefruit mercaptan, a sulfur-containing terpene, is one of the aroma compounds influencing taste and odor of grapefruit, compared with other citrus fruits.[24]

Drug interactions

Grapefruit and grapefruit juice have been found to interact with numerous drugs and in many cases, to result in adverse direct and/or side effects (if dosage is not carefully adjusted.)[25]

This happens in two very different ways. In the first, the effect is from bergamottin, a natural furanocoumarin in both grapefruit flesh and peel that inhibits the CYP3A4 enzyme (among others from the P450 enzyme family responsible for metabolizing 90% of drugs). The action of the CYP3A4 enzyme itself is to metabolize many medications.[26][27] If the drug's breakdown for removal is lessened, then the level of the drug in the blood may become too high or stay too long, leading to adverse effects.[27] On the other hand, some drugs must be broken down to become active, and inhibiting CYP3A4 may lead to reduced drug effects.

The other effect is that grapefruit can block the absorption of drugs in the intestine.[27] If the drug is not absorbed, then not enough of it is in the blood to have a therapeutic effect.[27] Each affected drug has either a specific increase of effect or decrease.

One whole grapefruit, or a glass of 200 ml (6.8 US fl oz) of grapefruit juice may cause drug overdose toxicity.[28] Typically, drugs that are incompatible with grapefruit are so labeled on the container or package insert.[27] People taking drugs should ask their health-care provider or pharmacist questions about grapefruit and drug interactions.[27]

Nutrition

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 138 kJ (33 kcal) |

8.41 g | |

| Sugars | 7.31 g |

| Dietary fiber | 1.1 g |

0.10 g | |

.8 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Thiamine (B1) | 3% 0.037 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 2% 0.020 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 2% 0.269 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 6% 0.283 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 3% 0.043 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 3% 10 μg |

| Choline | 2% 7.7 mg |

| Vitamin C | 40% 33.3 mg |

| Vitamin E | 1% 0.13 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 1% 12 mg |

| Iron | 0% 0.06 mg |

| Magnesium | 3% 9 mg |

| Manganese | 1% 0.013 mg |

| Phosphorus | 1% 8 mg |

| Potassium | 3% 148 mg |

| Zinc | 1% 0.07 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 90.48 g |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

Raw grapefruit is 90% water, 8% carbohydrates, 1% protein, and negligible fat (table). In a 100-g reference amount, raw grapefruit provides 33 Calories and is a rich source of vitamin C (40% of the Daily Value), with no other micronutrients in significant content.

Citric acid

Grapefruit juice contains about half the citric acid of lime or lemon juice, and about 50% more citric acid than orange juice.[29]

Grapefruit sweets

In Costa Rica, especially in Atenas, grapefruit are often cooked to remove their sourness, rendering them as sweets; they are also stuffed with dulce de leche, resulting in a dessert called toronja rellena (stuffed grapefruit).[30] In Haiti, grapefruit is used primarily for its juice (jus de Chadèque), but also is used to make jam (confiture de Chadèque).[31][32]

Parasites

Grapefruits are one of the most common hosts for fruit flies such as A. suspensa, which lay their eggs in overripe or spoiled grapefruits.[33] The larvae of these flies then consume the fruit to gain nutrients until they can proceed into the pupae stage. This parasitism has led to millions in economic costs for nations in Central America and southern North America.[34]

Other uses

Grapefruit has also been investigated in cancer medicine pharmacodynamics. Its inhibiting effect on the metabolism of some drugs may allow smaller doses to be used, which can help to reduce costs.[35]

Lifestyle magazines and websites sometimes recommend grapefruit as a stain remover for porcelain and enamel.[36][37]

Grapefruit relatives

Grapefruit is a pomelo backcross, a hybrid of pomelo × sweet orange, with sweet orange itself being a pomelo × mandarin hybrid.

The grapefruit is a parent to many hybrids:

- A tangelo is any hybrid of a tangerine and either a pomelo (pummelo) or a grapefruit

- 'Minneola': 'Duncan' grapefruit × 'Dancy' tangerine[38]

- 'Orlando' (formerly 'Take'): Bowen grapefruit × 'Dancy' tangerine (pollen parent)[38]

- 'Fairchild' is a clementine × 'Orlando' hybrid

- 'Seminole': 'Bowen' grapefruit × 'Dancy' tangerine[38]

- 'Thornton': tangerine × grapefruit, unspecified[38]

- 'Ugli': mandarin × grapefruit, probable (wild seedling)[38]

- 'Nova' is a second-generation hybrid: Clementine × 'Orlando' tangelo cross[38]

- The 'Oroblanco' and 'Melogold' grapefruits are hybrids between pummelo (C. maxima) and the grapefruit

Related citrus fruits include:

- Common sweet orange: pomelo × mandarin hybrid

- Bitter orange: a different pomelo × mandarin hybrid

- Mandelos: pomelo × mandarin

- Hyuganatsu may also be a pomelo hybrid

See also

- Grapefruit knife – Knife designed specifically for cutting grapefruit

- Grapefruit spoon – Kind of spoon intended for use with citrus fruit

- Grapefruit–drug interactions

- Naringenin

References

- Morton, Julia Frances (1987). "Grapefruit, Citrus paradisi". Fruits of Warm Climates. NewCROP, New Crop Resource Online Program, Center for New Crops and Plant Products, Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, Purdue University. pp. 152–158. ISBN 978-0-9610184-1-2. OCLC 16947184.

- Carrington, Sean; Fraser, Henry C. (2003). "Grapefruit". A~Z of Barbados Heritage. Macmillan Caribbean. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-0-333-92068-8.

One of many citrus species grown in Barbados. This fruit is believed to have originated in Barbados as a natural cross between sweet orange (C. sinesis) and shaddock (C. grandis), both of which originated in Asia and were introduced by Europeans in the 17th century. The grapefruit first appeared as an illustration entitled 'The Forbidden Fruit Tree' in The Natural History of Barbados (1750) by Rev. Griffith Hughes. This accords with the scientific name, which literally is 'citrus of paradise'. The fruit seems to have been fairly commonly available around that time, since George Washington in his Barbados Journal (1750-1751) mentions 'the Forbidden Fruit' as one of the local fruit available at a dinner party he attended. The plant was later described in the 1837 Flora of Jamaica as the Barbados Grapefruit. The historical arguments and experimental work on leaf enzymes and oils from possible parents all support a Barbadian origin for the fruit.

- Li, Xiaomeng; Xie R.; Lu Z.; Zhou Z. (July 2010). "The Origin of Cultivated Citrus as Inferred from Internal Transcribed Spacer and Chloroplast DNA Sequence and Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism Fingerprints". Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science. 135 (4): 341. doi:10.21273/JASHS.135.4.341. Archived from the original on 24 April 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- "How did the grapefruit get its name?" Library of Congress. Science Reference Service, Everyday Mysteries. Retrieved August 2, 2009.

- Texas grapefruit history Archived 2010-11-28 at the Wayback Machine, TexaSweet. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- Xiaomeng Li; Rangjin Xie; Zhenhua Lu; Zhiqin Zhou. "Genetic origin of cultivated citrus determined: Researchers find evidence of origins of orange, lime, lemon, grapefruit, other citrus species". Science Daily. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- Kumamoto, J.; Scora, R. W.; Lawton, H. W.; Clerx, W. A. (1987-01-01). "Mystery of the forbidden fruit: Historical epilogue on the origin of the grapefruit, Citrus paradisi (Rutaceae)". Economic Botany. 41 (1): 97–107. doi:10.1007/BF02859356. ISSN 0013-0001.

- Grapefruit: a fruit with a bit of a complex in Art Culinaire (Winter, 2007)

- "World Wide Words: Grapefruit". World Wide Words. Retrieved 2017-03-30.

- Admin (2010). "Welchman Hall Gully, Barbados". Barbados National Trust. Archived from the original on 16 August 2010. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

The Development of the Gully - The Gully was once part of a plantation owned by a Welshman called General William Asygell Williams over 200 years ago. Hence the name "Welchman Hall" gully. It was this man who first developed the gully with exotic trees and an orchard. Interestingly, the grapefruit is originally from Barbados and is rumoured to have started in Welchman Hall Gully.

- Barbados Seven Wonders: The Grapefruit Tree. Abstract

- Texas Citrus: Puzzling Beginnings. Article Archived 2007-01-25 at the Wayback Machine

- University of Florida: IFAS Extension; The Grapefruit. "Fact Sheet" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-28.

- "Manatee County a big part of citrus history". HeraldTribune.com. 2004-08-16. Retrieved 2011-12-17.

- "Grapefruit". www.hort.purdue.edu. Retrieved 2017-03-30.

- William J Broad (28 August 2007). "Useful Mutants, Bred With Radiation". New York Times.

- "MVD". mvgs.iaea.org. Retrieved 2017-03-30.

- Ahloowalia, B.S.; Maluszynski, M.; Nichterlein, K. (2004). "Global impact of mutation-derived varieties". Euphytica. 135 (2): 187–204. doi:10.1023/B:EUPH.0000014914.85465.4f.

- Sauls, Julian W. (1998). "Home fruit Production-Grapefruit". Retrieved 2013-07-22.

- Citrus Variety Collection. "Star Ruby grapefruit". Retrieved 2013-07-22.

- "Go Florida Grapefruit". Go Florida Grapefruit. Archived from the original on 2011-09-10. Retrieved 2011-12-17.

- "Grapefruit production in 2018, Crops/Regions/World list/Production Quantity (pick lists)". UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT). 2019. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- Zheng, Huiwen; Zhang, Qiuyun; Quan, Junping; Zheng, Qiao; Xi, Wanpeng (2016). "Determination of sugars, organic acids, aroma components, and carotenoids in grapefruit pulps". Food Chemistry. 205: 112–121. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.03.007. ISSN 0308-8146. PMID 27006221.

- A. Buettner; P. Schieberle (1999). "Characterization of the Most Odor-Active Volatiles in Fresh, Hand-Squeezed Juice of Grapefruit (Citrus paradisi Macfayden)". J. Agric. Food Chem. 47 (12): 5189–5193. doi:10.1021/jf990071l. PMID 10606593.

- Bailey DG, Dresser G, Arnold JM (March 2013). "Grapefruit-medication interactions: forbidden fruit or avoidable consequences?". CMAJ. 185 (4): 309–16. doi:10.1503/cmaj.120951. PMC 3589309. PMID 23184849.

- Renee, Janet. "Does Grapefruit Inhibit Liver Enzymes?". sfgate.com. SF Gate. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- Mitchell, Steve (19 February 2016). "Why Grapefruit and Medication Can Be a Dangerous Mix". Consumer Reports. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- Bailey, D. G.; Dresser, G.; Arnold, J. M. O. (2012). "Grapefruit-medication interactions: Forbidden fruit or avoidable consequences?". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 185 (4): 309–316. doi:10.1503/cmaj.120951. ISSN 0820-3946. PMC 3589309. PMID 23184849.

- Penniston KL, Nakada SY, Holmes RP, Assimos DG (2008). "Quantitative Assessment of Citric Acid in Lemon Juice, Lime Juice, and Commercially-Available Fruit Juice Products". Journal of Endourology. 22 (3): 567–570. doi:10.1089/end.2007.0304. PMC 2637791. PMID 18290732.

- Ben Box, ed. (1993). "Costa Rica - The Meseta Central". 1994 Mexico & Central America Handbook. Sarah Cameron, Sebastian Ballard (4 ed.). Bath, England: Trade and Travel Publications Ltd. p. 682. ISBN 978-0900751462.

- Monrose, Gregory Salomon (ed.). "Standardisation d'une formulation de confiture de chadèque et évaluation des paramètres physico-chimiques, microbiologiques et sensoriels" (in French). Université d'Etat d'Haiti (UEH / FAMV) - Ingenieur Agronome 2009. Retrieved 5 June 2017 – via Memoire Online.

- Bidault, Blandine; Gattegno, Isabelle, eds. (1984). Le point sur la transformation des fruits tropicaux (in French). Paris: Groupe de recherche et d'echanges technologiques (GRET). p. 46.

- van Whervin, L. Walter (March 1974). "Some Fruitflies (Tephritidae) in Jamaica". PANS Pest Articles & News Summaries. 20 (1): 11–19. doi:10.1080/09670877409412331. ISSN 0030-7793.

- McPheron, Bruce A. Steck, Gary J. (1996). Fruit fly pests : a world assessment of their biology and management. St. Lucie Press. ISBN 1574440144. OCLC 34343237.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Gandey, Allison (July 18, 2007). "Cut Cancer Drug Costs By Exploring Food Interactions". Medscape. Retrieved 2017-03-30.

- "How to Clean Your Bathtub with Grapefruit and Salt: 6 Steps". m.wikihow.com. Retrieved 2019-03-08.

- "How To Naturally Clean a Bathtub with Grapefruit and Salt". Apartment Therapy. Retrieved 2019-03-08.

- Morton, Julia F. (1987). "Tangelo". Fruits of warm climates. Miami, FL. pp. 158–160. ISBN 0-9610184-1-0.

External links

| Look up grapefruit in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Citrus Paradisi group. |