FN FAL

The FAL (French: Fusil Automatique Léger, English: Light Automatic Rifle) is a battle rifle designed by Belgian small arms designer Dieudonné Saive and manufactured by FN Herstal.

| FAL | |

|---|---|

A standard FAL made by FN | |

| Type | Battle rifle |

| Place of origin | Belgium |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1953–present |

| Used by | 90+ countries (See Users) |

| Wars | See Conflicts |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Dieudonné Saive |

| Designed | 1947–53 |

| Manufacturer | |

| Produced | 1953–present (Production by FN stopped in 1988) |

| No. built | 7,000,000[1] |

| Variants | See Variants |

| Specifications (FAL 50) | |

| Mass |

|

| Length |

|

| Barrel length |

|

| Cartridge | 7.62×51mm NATO, .280 British[2] |

| Action | Short-stroke gas piston, tilting breechblock[2] |

| Rate of fire | 700 rounds/min (fully automatic), variable (semi-automatic) |

| Muzzle velocity |

|

| Effective firing range |

|

| Feed system | 20- or 30-round detachable box magazine. 50-round drum magazines are also available.[3] |

| Sights | ramped aperture rear sight (adjustable from 200 to 600 m/yd in 100 m/yd increments) post front sight |

During the Cold War the FAL was adopted by many countries of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), with the notable exception of the United States. It is one of the most widely used rifles in history, having been used by more than 90 countries.[4] Because of its prevalence and widespread usage among the militaries of many NATO and first world countries during the Cold War, it received the title "The right arm of the Free World".[2]

It is chambered for the 7.62×51mm NATO cartridge (although originally designed for the .280 British intermediate cartridge). The British Commonwealth variant of the FAL was redesigned from FN's metrical FAL into British imperial units and was produced under licence as the L1A1 Self-Loading Rifle.

History

In 1946, the first FAL prototype was completed. It was designed to fire the intermediate 7.92×33mm Kurz cartridge developed and used by the forces of Germany during World War II (with the Sturmgewehr 44 assault rifle). After testing this prototype in 1948, the British Army urged FN to build additional prototypes, including one in bullpup configuration, chambered for their new .280 British [7x43mm] caliber intermediate cartridge.[5] After evaluating the single bullpup prototype, FN decided to return instead to their original, conventional design for future production.[5]

In 1950, the United Kingdom presented the redesigned FN rifle and the British EM-2, both in .280 British calibre, to the United States for comparison testing against the favoured United States Army design of the time—Earle Harvey's T25.[6] It was hoped that a common cartridge and rifle could be standardized for issue to the armies of all NATO member countries. After this testing was completed, U.S. Army officials suggested that FN should redesign their rifle to fire the U.S. prototype ".30 Light Rifle" cartridge. FN decided to hedge their bets with the U.S., and in 1951 even made a deal that the U.S. could produce FALs royalty-free, given that the UK appeared to be favouring their own EM-2.

This decision appeared to be correct when the British Army decided to adopt the EM-2 (as Rifle No.9 Mk1) and .280 British cartridge.[5] This decision was later rescinded after the Labour Party lost the 1951 General Election and Winston Churchill returned as Prime Minister. It is believed that there was a quid pro quo agreement between Churchill and U.S. President Harry Truman in 1952 that the British accept the .30 Light Rifle cartridge as NATO standard in return for the U.S. acceptance of the FN FAL as NATO standard.[7] The .30 Light Rifle cartridge was in fact later standardized as the 7.62 mm NATO; however, the U.S. insisted on continued rifle tests. The FAL chambered for the .30 Light Rifle went up against the redesigned T25 (now redesignated as the T47), and an M1 Garand variant, the T44. Eventually, the T44 won, becoming the M14. However, in the meantime, most other NATO countries were evaluating and selecting the FAL.

FN created what is possibly the classic post-war battle rifle. Formally introduced by its designer Dieudonné Saive in 1951, and produced two years later, it has been described as the "Right Arm of the Free World."[8] The FAL battle rifle has its Warsaw Pact counterpart in the AKM, each being fielded by dozens of countries and produced in many of them. A few, such as Israel and South Africa, manufactured and issued both designs at various times. Unlike the Soviet AKM assault rifle, the FAL utilized a heavier full-power rifle cartridge.

Design details

The FAL operates by means of a gas-operated action very similar to that of the Russian SVT-40. The gas system is driven by a short-stroke, spring-loaded piston housed above the barrel, and the locking mechanism is what is known as a tilting breechblock. To lock, it drops down into a solid shoulder of metal in the heavy receiver much like the bolts of the Russian SKS carbine and French MAS-49 series of semi-automatic rifles. The gas system is fitted with a gas regulator behind the front sight base, allowing adjustment of the gas system in response to environmental conditions. The piston system can be bypassed completely, using the gas plug, to allow for the firing of rifle grenades and manual operation.[9] The FAL's magazine capacity ranges from five to 30 rounds, with most magazines holding 20 rounds. In fixed stock versions of the FAL, the recoil spring is housed in the stock, while in folding-stock versions it is housed in the receiver cover, necessitating a slightly different receiver cover, recoil spring, and bolt carrier, and a modified lower receiver for the stock.[10] For field stripping the FAL can be opened. During opening the rifle rotates around a two piece pivot lock and pin assembly located between the trigger guard and magazine well to give access to the action and piston system. This opening method causes a suboptimal iron sight line as the rear sight element is mounted on the lower receiver and the front sight element of the sight line is mounted on the upper receiver/barrel and hence are fixed to two different movable subassemblies. The sight radius for the FAL 50.00 and FAL 50.41 models is 553 mm (21.8 in) and for the 50.61 and FAL 50.63 models 549 mm (21.6 in).

FAL rifles have also been manufactured in both light and heavy-barrel configurations, with the heavy barrel intended for automatic fire as a section or squad light support weapon. Most heavy barrel FALs are equipped with bipods, although some light barrel models were equipped with bipods, such as the Austrian StG58 and the German G1, and a bipod was later made available as an accessory.

Among other 7.62×51mm NATO battle rifles at the time, the FN FAL had relatively light recoil, due to the user-adjustable gas system being able to be tuned via a regulator in fore-end of the rifle, which allowed for excess gas which would simply increase recoil to bleed off. The regulator is an adjustable gas port opening that adjusts the rifle to function reliably with various propellant and projectile specific pressure behavior, making the FAL not ammunition specific. In fully automatic mode, however, the shooter receives considerable abuse from recoil, and the weapon climbs off-target quickly, making automatic fire only of marginal effectiveness.[11] Many military forces using the FAL eventually eliminated full-automatic firearms training in the light-barrel FAL.

Variants

FN production variants

Depending on the variant and the country of adoption, the FAL was issued as either semi-automatic only or select-fire (capable of both semi-automatic and fully automatic firing modes).

LAR 50.41 & 50.42 (FAL HBAR & FALO)

- Also known as FALO as an abbreviation from the French Fusil Automatique Lourd;

- Heavy barrel for sustained fire with a 30-round magazine as a squad automatic weapon;

- Known in Canada as the C2A1, it was their primary squad automatic weapon until it was phased out during the 1980s in favor of the C9, which has better accuracy and higher ammunition capacity than the C2;

- Known to the Australian Army as the L2A1, it was replaced by the FN Minimi. The L2A1 or 'heavy barrel' FAL was used by several Commonwealth nations and was found to frequently experience a failure to feed after firing two rounds from a full magazine when in automatic mode.

- The 50.41 is fitted with a synthetic buttstock, while the 50.42's buttstock is made from wood.

FAL 50.61 (FAL FS)

- Folding-stock, standard 533 mm (21.0 in) barrel length.

FAL 50.62 (FAL PARA )

- Folding-stock, shorter 458 mm (18.03 inch) barrel, paratrooper version and folding charging handle.

FAL 50.63 (FAL PARA 2 )

- Folding-stock, shorter 436 mm (17.16 inch) barrel, paratrooper version, folding charging handle. This shorter version was requested by Belgian paratroopers. The upper receiver was not cut for a carry handle, the charging handle on the 50.63 was a folding model similar to the L1A1 rifles, which allowed the folded-stock rifle to fit through the doorway of their C-119 Flying Boxcar when worn horizontally across the chest.

FAL 50.64 (FAL PARA 3)

- Folding-stock, standard 533 mm (21.0 in) barrel length, 'Hiduminium' aluminium alloy lower receiver.

Other FN Variants

- FN Universal Carbine (1947): An early FAL prototype chambered for the 7.92×33mm Kurz round. The 7.92mm Kurz round was used as a placeholder for the future mid-range cartridges being developed by Britain and the United States at the time.

- FAL .280 Experimental Automatic Carbine, Long Model (1951): A FAL variant chambered for the experimental .280 British (7×43mm) round. It was designed for a competition at Aberdeen Proving Grounds, Aberdeen, Maryland. Although the EM-2 "bullpup" did well, American observers protested that the small-bore .280-caliber round lacked the power and range of a medium-bore .30-caliber round. British observers in return claimed the experimental American .30-caliber T65 round (7.62×51mm) was too powerful to control in automatic fire. Britain was forced to abandon the promising .280 round and adopt the American-designed .30-caliber T65 as the 7.62×51mm NATO cartridge. The EM-2 couldn't be rechambered for the longer and more powerful cartridge and the Americans didn't yet have a working service rifle of their own. Britain and Canada adopted the Belgian 7.62mm FN FAL instead as the L1 Self-Loading Rifle (SLR).

- FAL .280 Experimental Automatic Carbine, Short Model (1951): A bullpup-frame version of the FAL chambered in .280 British designed to compete with the British EM-1 and EM-2 bullpup rifles. It also was demonstrated at the Aberdeen Proving Grounds tests, but was never put into full production.

Sturmgewehr 58

| Sturmgewehr 58 | |

|---|---|

StG-58 with DSA Type I receiver | |

| Type | Battle rifle |

| Place of origin | Belgium and Austria |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1958–1985 |

| Used by | Austria[12] |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Dieudonné Saive |

| Designed | 1956 |

| Manufacturer | Fabrique Nationale de Herstal and Steyr-Daimler-Puch |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 4.45 kg (9.81 lb) to 5.15 kg (11.35 lb) |

| Length | 1,100 mm (43 in) |

| Barrel length | 533 mm (21.0 in) |

| Cartridge | 7.62×51mm NATO |

| Action | Gas-operated, tilting breechblock |

| Muzzle velocity | 823 m/s (2,700 ft/s) |

| Effective firing range | 800 m (870 yd) |

| Feed system | 20-round detachable magazine |

| Sights | Iron sights |

The Sturmgewehr 58 (StG 58) is a selective fire (semi-automatic and fully automatic) battle rifle. The first 20,000 were manufactured by Fabrique Nationale d’Armes de Guerre-Herstal Belgique, but later the StG58 was manufactured under licence by Steyr-Daimler-Puch (now Steyr Mannlicher), and was formerly the standard rifle of the Österreichisches Bundesheer (Austrian Federal Army). It is essentially a user-customized version of the FAL and is still in use, mainly as a drill weapon in the Austrian forces. It was selected in a 1958 competition, beating the Spanish CETME and American Armalite AR-10.

Most StG 58s featured a folding bipod, and differ from the FAL by using a plastic stock rather than wood in order to reduce weight in the later production rifles (although some of the early FN-built production rifles did come with wooden stocks). The rifle can be distinguished from its Belgian and Argentine counterparts by its combination flash suppressor and grenade launcher. The foregrip was a two-part steel pressing.

Steyr-built StG 58s had a hammer forged barrel that was considered to be the best barrel fitted to any FAL. Some StG58s had modifications made to the fire mode selector so that the fully automatic option was removed, leaving the selector with only safe and single-shot positions. The StG 58 was replaced by the Steyr AUG (designated StG 77) in 1977, although the StG 58 served with many units as the primary service rifle through the mid-1980s.

Olin/Winchester FAL

A semi-automatic, twin-barrel variant chambered in the 5.56mm "Duplex" round during Project SALVO. This weapon was designed by Stefan Kenneth Janson who previously designed the EM-2 rifle.

Armtech L1A1 SAS

Dutch company Armtech built the L1A1 SAS, an assault-carbine variant of the L1A1 with a barrel length of 290 mm (11.4 inches).[13] This was similar to short-barreled L1A1 carbines used by the ANZAC forces in Vietnam.

DSA FAL (DSA-58)

American company DSA (David Selvaggio Arms) manufactures a copy of the FAL called the DSA-58 that is made with the same Steyr-Daimler-Puch production line equipment as the StG-58. It comes with a 406 mm (16 in), 457 mm (18 in) or 533 mm (21 in) barrel, an aluminum-alloy lower receiver, and improved Glass-filled Nylon furniture. Civilian models are semi-automatic, but military and Law Enforcement clients can procure select-fire models that have a fully automatic cyclic rate of 750 rounds/minute. The DSA-58 can use any metric-measurement FAL magazines, which come in 5, 10, 20 or 30-round capacities.

- The DSA-58 OSW (Operational Specialist Weapon) is an assault carbine version of the paratrooper model of the FAL. It has a side-folding Enhanced PARA polymer stock, shorter 279 mm (11 inch) or 330 mm (13 inch) barrel and an optional full-auto setting.

- The DSA-58 CTC (Compact Tactical Carbine) is a carbine version of the FAL. It has a side-folding Enhanced PARA polymer stock, shorter 413 mm (16.25 inch) barrel and an optional full-auto setting. Overall Length: 927 mm (36.5 inches) Weight: 3.74 kg (8.25 lbs).

Production and use

The FAL has been used by over 90 countries, and some seven million have been produced.[1][4] The FAL was originally made by Fabrique Nationale de Herstal (FN) in Liège, Belgium, but it has also been made under license in fifteen countries.[14] As of August 2006, new examples were still being produced by at least four different manufacturers worldwide.[15]

A distinct sub-family was the Commonwealth inch-dimensioned versions that were manufactured in the United Kingdom and Australia (as the L1A1 Self Loading Rifle or SLR), and in Canada as the C1. The standard metric-dimensioned FAL was manufactured in South Africa (where it was known as the R1), Brazil, Israel, Austria and Argentina. Both the SLR and FAL were also produced without license by India.[16][17]

Mexico assembled FN-made components into complete rifles at its national arsenal in Mexico City. The FAL was also exported to many other countries, such as Venezuela, where a small-arms industry produces some basically unchanged variants, as well as ammunition. By modern standards, one disadvantage of the FAL is the amount of work which goes into machining the complex receiver, bolt and bolt carrier. Some theorized that the movement of the tilting bolt mechanism tends to return differently with each shot, affecting inherent accuracy of the weapon, but this has been proven to be false. The FAL's receiver is machined, while most other modern military rifles use quicker stamping or casting techniques. Modern FALs have many improvements over those produced by FN and others in the mid-20th-century.

Argentina

The Argentine Armed Forces officially adopted the FN FAL in 1955, but the first FN made examples did not arrive in Argentina until the autumn of 1958. Subsequently, in 1960, licensed production of FALs began and continued until the mid-to-late 1990s, when production ceased. In 2010, a project to modernize all existing FAL and to produce an unknown number of them was approved. This project was called FAL M5.

Argentine FALs were produced by the government-owned arsenal FM (Fabricaciones Militares) at the Fábrica Militar de Armas Portátiles "Domingo Matheu" (FMAP "DM") in Rosario. The acronym "FAL" was kept, its translation being "Fusil Automático Liviano", (Light Automatic Rifle). Production weapons included "Standard" and "Para" (folding buttstock) versions. Military rifles were produced with the full auto fire option. The rifles were usually known as the FM FAL, for the "Fabricaciones Militares" brand name (FN and FM have a long-standing licensing and manufacturing agreement). A heavy barrel version, known as the FAP (Fusil Automático Pesado, or heavy automatic rifle) was also produced for the armed forces, to be used as a squad automatic weapon. The Argentine 'heavy barrel' FAL, also used by several other nations, was found to frequently experience a failure to feed after firing two rounds from a full magazine when in automatic mode.

A version of the FALMP III chambered in the 5.56×45mm NATO cartridge was developed in the early 1980s. It used M16 type magazines but one version called the FALMP III 5.56mm Type 2 used Steyr AUG magazines. The FARA 83 (Fusil Automático República Argentina) was to replace the Argentine military's FAL rifles. The design borrowed features from the FAL such as the gas system and folding stock. It seems to have been also influenced to some degree by other rifles (the Beretta AR70/223, M16, and the Galil). An estimated quantity of between 2,500 and 3,000 examples were produced for field testing, but military spending cuts killed the project in the mid-1980s.

There was also a semi-automatic–only version, the FSL, intended for the civilian market. Legislation changes in 1995 (namely, the enactment of Presidential Decree Nº 64/95) imposed a de facto ban on "semi-automatic assault weapons". Today, it can take up to two years to obtain a permit for the ownership of an FSL. The FSL was offered with full or folding stocks, plastic furniture and orthoptic sights.

Argentine FALs saw action during the Falklands War (Falklands-Malvinas/South Atlantic War), and in different peace-keeping operations such as in Cyprus and the former Yugoslavia. Rosario-made FALs are known to have been exported to Bolivia (in 1971), Colombia, Croatia (during the wars in former Yugoslavia during the 1990s), Honduras, Nigeria (this is unconfirmed, most Nigerian FALs are from FN in Belgium or are British-made L1A1s), Peru, and Uruguay (which reportedly took delivery of some Brazilian IMBEL-made FALs as well). Deactivated Argentinean FALs from the many thousands captured during the Falklands War are used by UK forces as part of the soldier's load on some training courses run over public land in the UK.

The Argentine Marine Corps, a branch of the Argentine Navy, has replaced the FN/FM FAL in front line units, adopting the U.S. M16A2. The Argentine Army has expressed its desire to acquire at least 1,500 new rifles chambered for the 5.56×45mm NATO SS109/U.S. M855 (.223 Remington) cartridge, to be used primarily by its peacekeeping troops on overseas deployments.

The US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) secretly purchased several thousand Argentine FAL rifles in 1981, which were supplied to the Nicaraguan Contras rebel group. These rifles have since appeared throughout Central America in use with other organizations.

These rifles are currently being modernized to a new standard, the FAL M5 (or FAL V), which uses polymer parts to reduce weight, and has Picatinny rails and optic mounts for carrying accessories, that created these variants:

- FAMTD: Fusil Argentino Modelo Tirador Destacado - Cañón Pesado (Argentine Designated Marksman Rifle - Heavy Barrel), DMR variant. It has a range of 650 meters.

- FAMTD: Fusil Argentino Modelo Tirador Destacado - Cañón Liviano (Argentine Designated Marksman Rifle - Light Barrel), It has a light bipod, a telescopic sight (10 × 50) with coupling for night vision, a new top-mount system for the application cited above and a cylinder head with cheekrest.

- FAMA: Fusil Argentino Modelo Asalto (Argentine Assault Rifle Model), this is the assault rifle version, using 7.62mm ammunition. It has a rate of fire of 700 rounds per minute, and it has a total length of 591 mm. Able to incorporate holographic sights, laser flashlight, tactical grip or a 40mm grenade launcher..

- FAMCa: Fusil Argentino Modelo Carabina (Argentine Rifle Carbine Model), this is the carbine variant.

Brazil

.jpg)

Brazil took delivery of a small quantity of FN-made FAL rifles for evaluation as early as 1954. Troop field testing was performed with FN made FALs between 1958 and 1962. Then, in 1964, Brazil officially adopted the rifle, designating the rifle M964 for 1964. Licensed production started shortly thereafter at the Indústria de Material Bélico do Brasil (IMBEL), in Itajubá in the state of Minas Gerais. The folding stock version was designated M964A1. By the late 1980s/early 1990s, IMBEL had manufactured some 200,000 M964 rifles. Later Brazilian made FALs have Type 3, hammer forged receivers. Early FN made FALs for Brazil are typical FN 1964 models with Type 1 or Type 2 receivers, plastic stock, handguard, and pistol grip, 22 mm cylindrical flash hider for grenade launching, and plastic model "D" carrying handle. Brazilian-made FALs are thought to have been exported to Uruguay. A heavy barrel version, known as the FAP (Fuzil Automático Pesado, or heavy automatic rifle) was also produced for the armed forces, to be used as a squad automatic weapon.

.jpg)

Brazil's planned service weapon was a development of the FAL in 5.56×45mm. Known as the MD-2 and MD-3 assault rifles, it was also manufactured by IMBEL. The first prototype, the MD-1, came out around 1983. In 1985, the MD-2 was presented and adopted by the Military Police. Its new 5.56×45mm NATO chambering aside, the MD-2/MD-3 is still very similar to the FAL and externally resembles it, changes include a change in the locking system, which was replaced by an M16-type rotating bolt. The MD-2 and MD-3 use STANAG magazines, but have different buttstocks. The MD-2 features an FN 50.63 'para' side-folding stock, while the MD-3 uses the same fixed polymer stock of the standard FAL.

However, Brazil's current service weapon is a Brazilian FAL-based assault rifle in 5.56×45mm and 7.62×51mm versions, with Assault Rifle and Carbine variants, including a Sniper and CQB rifle, called the IA2, also produced by IMBEL.

Along with the IA2, MD-2 and MD-3 assault rifles, Brazil produces the M964A1/Pelopes (Special Operations Platoon), with an 11" barrel, 3-point sling and a Picatinny rail with a tactical flashlight and sight.[18]

Brazilian Army officially used the FAP (Fuzil Automático Pesado, or heavy automatic rifle) as its squad automatic weapon until 2013/2014, when the FN Minimi was adopted to replace it. The Marine Corps and Air Force also adopted the Minimi to replace the FAP.[19]

IMBEL also produced a semi-automatic version of the FAL for Springfield Armory, Inc. (not to be confused with the US military Springfield Armory), which was marketed in the US as the SAR-48 (standard model) and SAR-4800 (made after 1989 with some military features removed to comply with new legislation), starting in the mid-1980s. IMBEL-made receivers have been much in demand among American gunsmiths building FALs from "parts kits."

IMBEL in 2014 offered the FAL in 9 versions:[20]

- M964, the standard length semi-auto and full auto.

- M964 MD1, short barrel semi-auto and full auto.

- M964 MD2, standard length semi-auto only.

- M964 MD3, short barrel semi-auto only.

- M964A1, folding stock standard barrel semi-auto and full auto.

- M964A1 MD1, folding stock short barrel semi-auto and full auto.

- M964A1 MD2, folding stock standard barrel semi-auto only.

- M964A1 MD3, folding stock short barrel semi-auto only.

- M964A1/Pelopes, short barrel semi-auto and full auto with Picatinny rail.

Currently, Brazilian Army and Marine Corps Groups still use the FAL as their main rifle, as many troops are not yet issued the IA2.

Germany

The first German FALs were from an order placed in late 1955/early 1956, for several thousand FN FAL so-called "Canada" models with wood furniture and the prong flash hider. These weapons were intended for the Bundesgrenzschutz (border guard) and not the nascent Bundeswehr (army), which at the time used M1 Garands and M1/M2 carbines. In November 1956, however, West Germany ordered 100,000 additional FALs, designated the G1, for the army. FN made the rifles between April 1957 and May 1958. G1s served in the West German Bundeswehr for a relatively short time in the late 1950s and early 1960s, before they were replaced by the Spanish CETME Modelo 58 rifle in 1959 (which was extensively reworked into the later G3 rifle). The G1 featured a pressed metal handguard identical to the ones used on the Austrian Stg. 58, as well as the Dutch and Greek FALs, this being slightly slimmer than the standard wood or plastic handguards, and featuring horizontal lines running almost their entire length. G1s were also fitted with a unique removable prong flash hider, adding another external distinction. The main reason for the replacement of the G1 in Germany was the refusal of the Belgians to grant a license for production of the weapon in Germany.[21] Many G1 FALs were passed on to Turkey after their withdrawal from German service. Of note is the fact that the G1 was the first FAL variant with the 3mm lower sights specifically requested by Germany, previous versions having the taller Commonwealth-type sights also seen on Israeli models.

Greece

FN FAL rifles produced in Belgium were adopted by the Greek Army before the adoption of HK G3A3s rifles produced under license by Hellenic Arms Industry (ΕΒΟ). For a few years, FN FAL rifles were also produced under license by the Greek PYRKAL (ΠΥΡΚΑΛ) factory. FN FAL and FALO rifles were in use by the Greek Army Special Forces and IV Army Corps from 1973 till 1999, and are still in use by the Greek Coast Guard.[22][23]. FN FAL all models are still in service by Hellenic Police (Greek National Police Corp).

Israel

After the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) had to overcome several logistics problems which were a result of the wide variety of old firearms that were in service. In 1955 the IDF adopted the IMI-produced Uzi submachine gun. To replace the German Mauser Kar 98k and some British Lee–Enfield rifles, the IDF decided in the same year to adopt the FN FAL as its standard-issue infantry rifle, under the name Rov've Mitta'enn or Romat (רומ"ט), an abbreviation of "Self-Loading Rifle". The FAL version ordered by the IDF came in two basic variants, both regular and heavy-barrel (automatic rifle), and were chambered for 7.62mm NATO ammunition. In common with heavy-barrel FALs used by several other nations, the Israeli 'heavy barrel' FAL (called the Makle'a Kal, or Makleon) was found to frequently experience a failure to feed after firing two rounds from a full magazine when in automatic mode. The Israeli FALs were originally produced as selective-fire rifles, though later light-barrel rifle versions were altered to semi-automatic fire only. The Israeli models are recognizable by a distinctive handguard with a forward perforated sheet metal section, and a rear wood section unlike most other FALs in shape, and their higher 'Commonwealth'-type sights. Israel has been a keen user of rifle grenades, in particular the AT 52 which is often seen in photographs with the FAL.[24][25]

The Israeli FAL first saw action in relatively small quantities during the Suez Crisis of 1956, the Six-Day War in June 1967, the War of Attrition of 1967 until 1970, it was the standard Israeli rifle. During the Yom Kippur War of October 1973 it was still in front-line service as the standard Israeli rifle, though increasing criticism eventually led to the phasing-out of the weapon. Israeli forces were primarily mechanized in nature; the long, heavy FAL slowed deployment drills, and proved exceedingly difficult to maneuver within the confines of a vehicle.[26][27] Additionally, Israeli forces experienced repeated jamming of the FAL due to heavy sand and dust ingress endemic to Middle Eastern desert warfare, requiring repeated field-stripping and cleaning of the rifle, sometimes while under fire.[27] During the later stages of the Yom Kippur War, it was noted that some Israeli soldiers had informally exchanged their FALs for the far more reliable Soviet Kalashnikov AK-47 assault rifles taken from dead and captured Arab soldiers. Though the IDF evaluated a few modified FAL rifles with 'sand clearance' slots in the bolt carrier and receiver (which were already part of the Commonwealth L1A1/C1A1 design), malfunction rates did not significantly improve.[28] The Israeli FAL was eventually replaced by the M16 and the Galil (a weapon using the Soviet Kalashnikov operating system, and chambered in either 5.56×45 or 7.62 NATO),[27][28] though the FAL remained in production in Israel until 1986.[29]

Rhodesia

Like most British dependencies of the time, Southern Rhodesia had equipped its security forces with the British L1A1, or SLR, by the early 1960s. Following that country's unilateral declaration of independence in 1965, new rifles could not be readily procured from the UK, so Belgian FNs and South African R1s were imported instead. The older L1s subsequently completed their service with the British South Africa Police and to a lesser extent territorial troops in the Rhodesia Regiment .[30]

During the Rhodesian Bush War, security forces fitted some standard FNs with customised flash suppressors to reduce recoil on fully automatic fire. Rhodesian Security Forces seldom ever used the FN on automatic fire and were trained to use a "double tap" on semi-automatic in combat, as automatic fire was considered a total waste of ammunition. However, a few soldiers rejected these devices, which they claimed upset the balance of their weapons during close action.[30] In this theatre, the FN was generally considered superior to the Soviet Kalashnikovs or SKS carbines carried by communist-backed PF insurgents.[30]

Trade sanctions and the gradual erosion of South African support in the 1970s led to serious part shortages.[31] Consequently, shipments of G3s were accepted from Portugal, although the security forces considered these less reliable than the FAL.[30] Following Robert Mugabe's ascension to power in 1980, Rhodesia's remaining FNs were passed on to Zimbabwe, its successor state.[32] To simplify maintenance and logistics, the weapon initially remained a standard service rifle in the Zimbabwe Defence Forces. It was anticipated that more 7.62mm NATO ammunition would be imported to cover existing shortages, but a sabotage action carried out against the old Rhodesian Army stockpiles negated this factor. Zimbabwe promptly supplemented its surviving inventory with Soviet and North Korean arms.[33]

South Africa

The FAL was produced under licence in South Africa by Lyttleton Engineering Works, where it is known as the R1. The first South African-produced rifle, serial numbered 200001, was presented to the then Prime Minister, Dr Hendrik Verwoerd, by Armscor and is now on view at the South African National Museum of Military History in Johannesburg.[34]

Syria

Syria adopted the FN FAL in 1956. 12,000 rifles were bought in 1957.[35] The Syrian state produced 7.62×51mm cartridges[35] and is reported to have acquired FALs from other sources. During the Syrian Civil War, FALs from various sources, including Israel, were used by governmental forces, rebels, Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant and Kurdish forces.[35] The Syrian Arab Army and loyalist paramilitary forces used it as a designated marksman rifle.[36] At the end of 2012, the use of .308 Winchester cartridges may have caused these FALs to malfunction, thus reducing the popularity of the weapon.[37]

United States

Following World War II and the establishment of the NATO alliance, there was pressure to adopt a standard rifle, alliance-wide. The FAL was originally designed to handle intermediate cartridges, but in an attempt to secure US favor for the rifle, the FAL was redesigned to use the newly developed 7.62×51mm NATO cartridge. The US tested several variants of the FAL to replace the M1 Garand. These rifles were tested against the T44, essentially an updated version of the basic Garand design.[38] Despite the T44 and T48 showing performing similarly in trials,[38] the T44 was, for several reasons, selected and the US formally adopted the T44 as the M14 service rifle.

During the late 1980s and 1990s, many countries decommissioned the FAL from their armories and sold them en masse to United States importers as surplus. The rifles were imported to the United States as fully automatic guns. Once in the U.S., the FALs were "de-militarized" (upper receiver destroyed) to eliminate the rifles' character as an automatic rifle, as stipulated by the Gun Control Act of 1968 (GCA 68 currently prohibits the importation of foreign-made full-automatic rifles prior to the enactment of the Gun Control Act; semiautomatic versions of the same firearm were legal to import until the Semiautomatic Assault Rifle Ban of 1989). Thousands of the resulting "parts kits" were sold at generally low prices ($90 – $250) to hobbyists. The hobbyists rebuilt the parts kits to legal and functional semi-automatic rifles on new semi-automatic upper receivers. FAL rifles are still commercially available from a few domestic firms in semi-auto configuration: Entreprise Arms, DSArms, and Century International Arms. Century Arms created a semi-automatic version L1A1 with an IMBEL upper receiver and surplus British Enfield inch-pattern parts, while DSArms used Steyr-style metric-pattern FAL designs (this standard-metric difference means the Century Arms and DSArms firearms are not made from fully interchangeable batches of parts).

Venezuela

Until recently, the FAL was the main service rifle of the Venezuelan army, made under license by CAVIM.[39] The first batch of rifles to arrive in Venezuela were chambered in 7×49mm (also known as 7 mm Liviano or 7 mm Venezuelan). Essentially a 7×57mm round shortened to intermediate length, this caliber was jointly developed by Venezuelan and Belgian engineers motivated by a global move towards intermediate calibers. The Venezuelans, who had been exclusively using the 7×57mm round in their light and medium weapons since the turn of the 20th century, felt it was a perfect platform on which to base a calibre tailored to the particular rigours of the Venezuelan terrain.

Eventually the plan was dropped despite having ordered millions of rounds and thousands of weapons of this caliber. As the Cold War escalated, the military command felt it necessary to align with NATO despite not being a member, resulting in the adoption of the 7.62×51mm NATO cartridge and the rechambering of the 5,000 or so FAL rifles that had already arrived in 7×49mm by 1955–56.

Venezuela has bought 100,000 AK-103 assault rifles from Russia in order to replace the old FALs.[39] Although the full shipment arrived by the end of 2006, the FAL will remain in service with the Venezuelan Reserve Forces and the Territorial Guard.

Conflicts

In the more than 60 years of use worldwide, the FAL has seen use in conflicts all over the world. During the Falklands War, the FN FAL was used by both sides. The FAL was used by the Argentine armed forces and the L1A1 Self Loading Rifle (SLR), a semi-automatic only version of the FAL, was used by the armed forces of the UK and other Commonwealth nations.[41]

- Mau Mau Uprising:[42] British FN-made prototypes[40]

- Cuban Revolution[43]

- Bangladesh Liberation War[44]

- Congo Crisis[45]

- Bay of Pigs Invasion[2]

- Araguaia Guerrilla War

- Nigerian Civil War[46]

- Six-Day War[47][48]

- War of Attrition

- Moro conflict[49]

- Yom Kippur War[47]

- Portuguese Colonial War[50]

- Angolan Civil War[51]

- South African Border War[52]

- Rhodesian Bush War[53][54]

- Western Sahara War[55]

- Shaba II[56]

- Salvadoran Civil War[57]

- Falklands War[2]

- Lebanese Civil War

- Gulf War[58]

- Bougainville Civil War[59]

- Croatian war of independence, see "Former users".

- Burundian Civil War[60]

- First Congo War[61]

- Kivu conflict

- Mexican Drug War[62]

- 2010 Rio de Janeiro Security Crisis[59]

- Iraqi insurgency[63]

- Libyan Civil War[64][65]

- Syrian Civil War[66]

- Boko Haram insurgency[67]

- Yemeni Civil War (2015–present)

- Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen

- South Sudanese Civil War

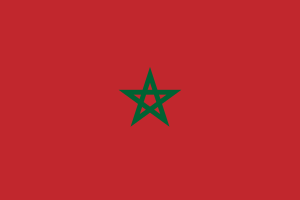

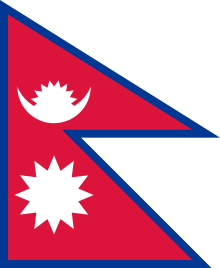

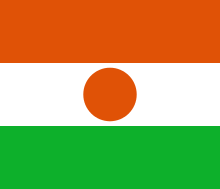

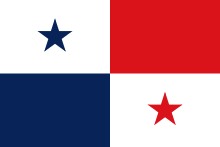

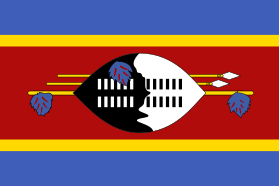

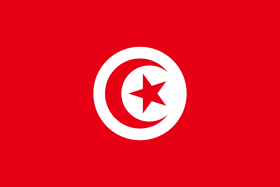

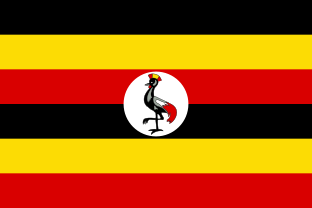

Users

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Non-state users

.svg.png)

- ex-Libyan FALs can be traced to Algeria, Chad, Egypt, Lebanon, Niger, Syria and Tunisia[90]

Former users

.svg.png)

%3B_Flag_of_Serbia_and_Montenegro_(2003%E2%80%932006).svg.png)

.svg.png)

See also

- FN-49, predecessor to the FAL

- L1A1 Self-Loading Rifle, the British Commonwealth pattern of the FAL

- FN CAL, an unsuccessful FN 5.56mm NATO assault rifle that externally resembles the FAL

- IMBEL MD97

- Ishapore 1A1 Indian Copy of FN FAL.

- ParaFAL

- Heckler & Koch G3, a German 7.62 battle rifle designed in the 1950s

- Desarrollos Industriales Casanave SC-2005, the Peruvian pattern upgrade of the FAL

References

- Aldis, Anne (2005). Soft Security Threats & Europe. Routledge. p. 83.

- Bishop, Chris. Guns in Combat. Chartwell Books, Inc (1998). ISBN 0-7858-0844-2.

- "Fabrique Nationale FN FAL Battle Rifle (1953)". MilitaryFactory. Archived from the original on 2 August 2014. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- Hogg, Ian (2002). Jane's Guns Recognition Guide. Jane's Information Group. ISBN 0-00-712760-X.

- "FN FAL (Belgium)". Archived from the original on 17 November 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- "Earl Harvey's T-25". powmadeak47.com. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012.

- Boring, War Is (5 October 2014). "The FN FAL Was Almost America's Battle Rifle". Archived from the original on 6 May 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- Cashner 2013, p. 5.

- "Tuning the FAL's Gas System". Archived from the original on 12 January 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- Popeneker, Maxim & Williams, Anthony (2005). Assault Rifle. The Crowood Press Ltd. ISBN 1-86126-700-2.

- J., Dougherty, Martin (2011). Small arms visual encyclopedia. London: Amber Books. p. 222. ISBN 9781907446986. OCLC 751804871.

- "The StG58: Austria's Select Fire FAL". www.smallarmsreview.com. Archived from the original on 2019-02-24. Retrieved 2019-02-23.

- "Armtech FAL SAS". Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- Bourne, Mike (2007). Arming Conflict: The Proliferation of Small Arms. Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-0230019331.

- "Multiplying the Sources: Licensed and Unlicensed Military Production" (PDF). Geneva: Small Arms Survey. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- "Legacies of War in the Company of Peace: Firearms in Nepal" (PDF). Geneva: Small Arms Survey. May 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2014. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- Graduate Institute of International Studies (2003). Small Arms Survey 2003: Development Denied. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 97–113. ISBN 978-0199251759.

- BASTOS, Carlos Stephani. FAL M964A1/Pelopes 7,62: Aproveitando melhor o que se tem Archived 2016-10-12 at the Wayback Machine (in Portuguese). Federal University of Juiz de Fora.

- "FN MINIMI - EB aposenta o FAP e adota a FN Mini Mitrailleuse". 2013-10-20. Archived from the original on 2016-10-12. Retrieved 2016-10-11 – via DefesaNet.

- Administrator. "Fuzil 7,62 M964 (FAL)". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- "Europe". web.prm.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2017-04-27. Retrieved 2017-06-26.

- Sazanidis

- Hellenic Army General Staff / Army History Directorate

- Cashner 2013, pp. 21–22:"The IDF has long been fond of the rifle grenade. For night assaults on prepared defensive positions, Israeli infantry often crept to within rifle grenade range. The assault was started with a volley of grenades onto the enemy positions intended to stun them and put their heads down, immediately followed by the infantry assault before their opponents could recover... As far back as the 1960s, S.L.A. Marshall noted: "Israel's infantry prefers the rifle-fired antitank grenade to the bazooka for shock effect on a group or bunker. At night, if the section should run into an ambush, the grenadier fires, and the others rush straight in, not firing""

- "Images of Israeli use of rifle grenades from 1956 onwards". 24 October 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- South African Military History Society Newsletter (June 2006) http://samilitaryhistory.org/6/06junnl.html Archived 2008-12-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Bodinson, Holt, "Century’s Golani Sporter: The Israeli-designed AK Hybrid is a Solid Performer", Guns Magazine, July 2007

- "Weapons Wizard Israeli Galili", Soldier of Fortune Magazine, March 1982

- Cashner 2013, pp. 21–22

- Chris Cocks (2002-04-03). Fireforce: One Man's War in the Rhodesian Light Infantry (July 1, 2001 ed.). Covos Day. pp. 139–141. ISBN 1-919874-32-1.

- Smith, Ian (1997). The Great Betrayal. London: Blake Publishing Ltd. pp. 74–75. ISBN 1-85782-176-9.

- Jones, Richard D. Jane's Infantry Weapons 2009/2010. Jane's Information Group; 35 edition (January 27, 2009). ISBN 978-0-7106-2869-5.

- Nelson, Harold (1983), Zimbabwe: a country study, The American University (Washington, D.C.), ISBN 0160015987

- "History of the FN-F.A.L. Rifle in South Africa". Southern African Arms and Ammunition Collectors Association. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- Jenzen-Jones & Spleeters 2015, p. 7.

- "La 104ème brigade de la Garde républicaine syrienne, troupe d'élite et étendard du régime de Damas". France-Soir (in French). 20 March 2017. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- Jenzen-Jones & Spleeters 2015, p. 23.

- Stevens, R. Blake, The FAL Rifle, Collector Grade Publications, ISBN 0-88935-168-6, ISBN 978-0-88935-168-4 (1993)

- Pablo Dreyfus. "A Recurrent Latin American Nightmare" (PDF). Federation of American Scientists. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-06-13. Retrieved 2010-04-01.

- Cashner 2013, p. 15.

- "Top Ten Combat Rifles". Military Channel. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- "Contre les Mau Mau". Encyclopédie des armes : Les forces armées du monde (in French). XII. Atlas. 1986. pp. 2764–2766.

- Cashner 2013, p. 66.

- "Arms for freedom". 29 December 2017. Retrieved 2019-08-31.

- Cashner 2013, pp. 41-42.

- McNab 2002, p. 185.

- Cashner 2013, p. 47.

- McNab 2002, p. 140.

- Schroeder, Matt (2013). "Captured and Counted: Illicit Weapons in Mexico and the Philippines" (PDF). Small Arms Survey 2013: Everyday Dangers. Cambridge University Press. p. 303. ISBN 978-1-107-04196-7.

- Cashner 2013, p. 46.

- Fitzsimmons, Scott (November 2012). "Callan's Mercenaries Are Defeated in Northern Angola". Mercenaries in Asymmetric Conflicts. Cambridge University Press. p. 155. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139208727.005. ISBN 978-1-107-02691-9.

- McNab 2002, p. 204.

- McNab, Chris (2002). 20th Century Military Uniforms (2nd ed.). Kent: Grange Books. p. 196. ISBN 1-84013-476-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cashner 2013, p. 43.

- Abdalahe, M'Beirik Ahmed (October 2015). Santana Pérez, Juan Manuel (ed.). El Nacionalismo Saharaui, de Zemla a la Organización de la Unidad Africana (PDF) (PhD) (in Spanish). Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. p. 335. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-04-19. Retrieved 2018-12-20.

- Sicard, Jacques (November 1982). "Les armes de Kolwezi". La Gazette des armes (in French). No. 111. pp. 25–30. Archived from the original on 2018-10-19. Retrieved 2018-10-18.

- Cashner 2013, pp. 66-68.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (1993). Armies of the Gulf War. Elite 45. Osprey Publishing. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-85532-277-6.

- Dom Rotheroe (Director) (2001). The Coconut Revolution.

- Small Arms Survey (2007). "Armed Violence in Burundi: Conflict and Post-Conflict Bujumbura" (PDF). The Small Arms Survey 2007: Guns and the City. Cambridge University Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-521-88039-8. Archived from the original on 2018-08-27. Retrieved 2018-08-29.

- Small Arms Survey 2005, p. 318.

- admin. "Mexican Drug War Fighters".

- Baker, Aryn (20 January 2014). "A Nightmare Returns". Time Magazine. p. 31.

- "Up Close With Mustafa Abud Al-Jeleil, Leader Of Libyan Rebels". World Crunch.com.com. Archived from the original on 2011-04-03. Retrieved 2011-03-12.

- "Gaddafi forces 'intercept arms from Qatar'". 2011-07-05. Archived from the original on 2011-08-18. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- "The FN FAL in Syria". 2014-06-08. Retrieved 2018-10-02.

- Savannah de Tessières (January 2018). At the Crossroads of Sahelian Conflicts: Insecurity, Terrorism, and Arms Trafficking in Niger (PDF) (Report). Small Arms Survey. p. 58. ISBN 978-2-940548-48-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2018-06-05.

- Jones, Richard D. Jane's Infantry Weapons 2009/2010. Jane's Information Group; 35th edition (January 27, 2009). ISBN 978-0-7106-2869-5.

- Berrigan, Frida; Ciarrocca, Michelle (November 2000). "Report: Profiling the Small Arms Industry - World Policy Institute - Research Project". World Policy Institute. Archived from the original on 2018-08-23. Retrieved 2018-08-29.

- Small Arms Survey (2005). "The Central African Republic: A Case Study of Small Arms and Conflict" (PDF). Small Arms Survey 2005: Weapons at War. Oxford University Press. p. 313. ISBN 978-0-19-928085-8. Archived from the original on 2018-08-30. Retrieved 2018-08-29.

- Katz, Sam (24 Mar 1988). Arab Armies of the Middle East Wars (2). Men-at-Arms 128. Osprey Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 9780850458008.

- Small Arms Survey 2012, p. 320.

- Lavery, Don (2011-11-06). "Irish Independent Article". Archived from the original on 2011-11-08. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- Anders, Holger (June 2014). Identifier les sources d'approvisionnement: Les munitions de petit calibre en Côte d'Ivoire (PDF) (in French). Small Arms Survey and United Nations Operation in Côte d'Ivoire. p. 15. ISBN 978-2-940-548-05-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-10-09. Retrieved 2018-09-05.

- Berman, Eric G. (March 2019). Beyond Blue Helmets: Promoting Weapons and Ammunition Management in Non-UN Peace Operations (PDF). Small Arms Survey/MPOME. p. 43.

- Jenzen-Jones, N.R.; McCollum, Ian (April 2017). Small Arms Survey (ed.). Web Trafficking: Analysing the Online Trade of Small Arms and Light Weapons in Libya (PDF). Working Paper No. 26. pp. 77, 79. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-10-09. Retrieved 2018-08-30.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scarlata, Paul (May 2012). "The military rifle cartridges of Burma/Myanmar". Shotgun News. Archived from the original on 2018-11-28. Retrieved 2018-11-27.

- "Licensed and unlicensed production of FN Herstal products, to August 2006" (PDF). Small Arms Survey. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-05. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- "Nigeria - Arms Procurement and Defense Industries". June 1991. Archived from the original on 2008-12-07. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- "DOSSIER - The Question of Arms in Africa". Agenzia Fides. Archived from the original on 2009-03-18. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- "The History of the FAL/LAR". Archived from the original on 2013-09-30.

- "The Situation In Zamboanga. FN FAL Identification Needed". The Firearm Blog. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- Jenzen-Jones & Spleeters 2015, p. 21.

- Small Arms Survey (2012). "Surveying the Battlefield: Illicit Arms In Afghanistan, Iraq, and Somalia". Small Arms Survey 2012: Moving Targets. Cambridge University Press. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-521-19714-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-08-31. Retrieved 2018-08-30.

- Ezell, 1988, p. 328

- Small Arms Illustrated, 2010

- "Modern Firearms". Archived from the original on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- Small Arms Survey (2015). "Waning Cohesion: The Rise and Fall of the FDLR–FOCA" (PDF). Small Arms Survey 2015: weapons and the world (PDF). Cambridge University Press. p. 202. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-01-28. Retrieved 2018-08-29.

- Small Arms Survey (2006). "Fuelling Fear: The Lord's Resistance Army and Small Arms" (PDF). Small Arms Survey 2006: Unfinished Business. Oxford University Press. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-19-929848-8. Archived from the original on 2018-08-30. Retrieved 2018-08-29.

- Jenzen-Jones & McCollum 2017, p. 49.

- Binnie, Jeremy; de Cherisey, Erwan (2017). "New-model African armies" (PDF). Jane's. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 June 2017.

- "Obuka Bojne Frankopan (Žutica)". YouTube. Botswanac. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- de Quesada, Alejandro (10 Jan 2009). The Bay of Pigs: Cuba 1961. Elite 166. pp. 60–61. ISBN 9781846033230.

- http://www.crveneberetke.com/i-tvoje-ce-rane-neko-da-vida/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Abbott, Peter (20 February 2014). Modern African Wars (4): The Congo 1960–2002. Men-at-Arms 492. Osprey Publishing. p. 14. ISBN 9781782000761.

- Jenzen-Jones & Spleeters 2015, p. 20.

- Ezell, 1988, p. 276

- Afonso, Aniceto and Gomes, Carlos de Matos, Guerra Colonial (2000), ISBN 972-46-1192-2, pp. 183–184, 358-359

- Afonso, Aniceto and Gomes, Carlos de Matos, Guerra Colonial (2000), ISBN 972-46-1192-2, pp. 358–359

- "The military rifle cartridges of Rhodesia Zimbabwe: from Cecil Rhodes to Robert Mugabe". Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- "Современное стрелковое оружие мира - Автоматы и штурмовые винтовки". Archived from the original on 17 November 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- A fonso, Aniceto and Gomes, Carlos de Matos. Guerra Colonial, 2000.

- Cashner, Bob (2013). The FN FAL Battle Rifle. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78096-903-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chanoff, David; Doan Van Toai. Vietnam, A Portrait of its People at War. London: Taurus & Co, 1996. ISBN 1-86064-076-1.

- Ezell, Clinton. Small Arms of the World, Stackpole Books, 1983.

- Hellenic Army General Staff / Army History Directorate, (in Greek).(Γενικό Επιτελείο Στρατού / Διεύθυνση Ιστορίας Στρατού), "The armament of Greek Army 1868 - 2000 (Οπλισμός Ελληνικού Στρατού 1868 2000)", Athens, Greece, 2000.

- Jenzen-Jones, N.R.; Spleeters, Damien (August 2015). Identifying & Tracing the FN Herstal FAL Rifle: Documenting signs of diversion in Syria and beyond (PDF). Australia: Armament Research Services Pty. Ltd. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-9924624-6-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pikula, Maj. Sam. The Armalite AR-10, 1998.

- Sazanidis, Christos. (in Greek). "Arms of the Greeks (Τα όπλα των Ελλήνων)". Maiandros (Μαίανδρος), Thessaloniki, Greece, 1995. ISBN 978-960-90213-0-2.

- Stevens, R. Blake. The FAL Rifle Classic Edition. Cobourg, Ontario, Canada: Collector Grade Publications Incorporated, 1993. ISBN 0-88935-168-6.

- Stevens, R. Blake. More on the Fabled FAL: A Companion to The FAL Rifle. Cobourg, Ontario, Canada: Collector Grade Publications Incorporated, 2011. ISBN 978-0-88935-534-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to FN FAL. |

- Additional information, including pictures at Modern Firearms

- The FAL Files

- The FN/FAL & L1A1 FAQ

- Manual Collection

- FN FAL Rifle Ejector Photos

- Video

- Video of operation on YouTube (in Japanese)

- FN FAL "Paratrooper" Model Presentation (MPEG)

_ACMAT_VLRA_2.jpg)