Cyclura nubila caymanensis

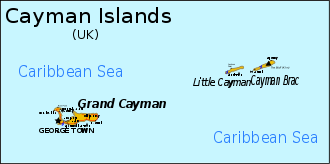

The Lesser Caymans iguana (Cyclura nubila caymanensis), also known as the Cayman Brac iguana, Cayman Island brown iguana or Sister Isles iguana, is a critically endangered subspecies of the Cuban iguana (Cyclura nubila). It is native to two islands to the south of Cuba: Cayman Brac and Little Cayman, which are also known as the Sister Isles due to their similar shapes and close proximity to each other. This subspecies is in decline due to habitat encroachment by human development and predation by feral dogs and cats. It is nearly extinct on Cayman Brac where less than 100 animals live, while Little Cayman supports a population of about 1,500 animals.

| Lesser Caymans iguana[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Iguania |

| Family: | Iguanidae |

| Genus: | Cyclura |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | C. n. caymanensis |

| Trinomial name | |

| Cyclura nubila caymanensis (Barbour & G.K. Noble, 1916) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy

The Lesser Caymans iguana, Cyclura nubila caymanensis, is only found on the islands of Little Cayman and Cayman Brac. It is a subspecies of Cuban iguana. This subspecies has been introduced to Grand Cayman, where it has interbred with that island's endemic blue iguana (C. lewisi).[3][4]

Its specific name, nubila, is Latin for 'cloudy', 'overcast' or 'gloomy'. According to one author the word means "gray" and in this instance was chosen in 1831 by the British zoologist John Edward Gray as a commemoration of himself, as opposed to the animal's color.[5] Its subspecific name caymanensis refers to the islands where it lives, the suffix -ensis meaning 'of' or 'pertaining to'.

Zoologists Thomas Barbour and Gladwyn Kingsley Noble first described the Lesser Caymans iguana as a species in 1916.[5] Chapman Grant, in an article published in 1940, subsumed the taxon as a subspecies of Cyclura macleayi [6]

In 1975 Albert Schwartz and Richard Thomas moved taxon to C. nubila, using the trinomial nomenclature, C. nubila caymanensis.[7] It evolved from and will readily interbreed with the nominate subspecies, as well as with Cyclura nubila lewisi.[3]

Anatomy and morphology

C. nubila caymanensis is a medium to large animal with an average total length between 30 and 40 inches.[8] Males are significantly larger than females.[9] The Lesser Caymans iguana has a skin color from light grey to green when mature, with a light blue or reddish-pink colored head, whereas females are more olive green, lacking any red or blue.[9] Young animals tend to be uniformly dark brown or green with faint dark bands.[9] Their distinctive black feet stand in contrast to the rest of their lighter overall body color.[9] Their eye-color is typically brown to blood red. An individual of this subspecies has been recorded as one of the longest lived of all species and subspecies of the genus Cyclura at 33 years.[10]

This species, like other species of Cyclura, is sexually dimorphic; males are larger than females, and have more prominent dorsal crests as well as larger femoral pores on their thighs, which are used to release pheromones.[8][9][11][12]

Distribution and habitat

Native to the islands of Little Cayman and Cayman Brac, this subspecies has been introduced to Grand Cayman.[3][4]

Like other members of the Genus Cyclura the Lesser Caymans iguana requires suitable areas in which to bask, forage, nest, and hide.[2] On Little Cayman these requirements are met in a variety of interior habitats even though the iguanas are widely dispersed.[2][13]

An ongoing population survey on Cayman Brac in 2012 has counted and pit-tagged 86 individuals. One of these was killed by a vehicle in April 2012. There are additional individuals which have been spotted but not yet captured and pit-tagged.

Diet

Like all Cyclura species the Lesser Caymans iguana is primarily herbivorous, consuming leaves, flowers and fruits from over 100 different plant species.[2][8] This diet is very rarely, if ever supplemented with animal matter.[2][8]

Mating

Mating occurs in April to May depending when the dry season ends, and 7-25 eggs are usually laid in May or June depending on the size and age of the female.[2] Due to being forced to dwell inland where the soil is rocky, the females often have to migrate to coastal areas in order to build their nests in the sand.[2][14] The hatchlings emerge from the nests in August to early September.[2]

Conservation

Endangered status

The Lesser Caymans iguana is critically endangered according to the current IUCN Red List endangered species.[2] The subspecies is vital to its native ecosystem as a seed disperser for native vegetation, and its extinction could have serious consequences as many of Little Cayman's and Cayman Brac's plants are not found elsewhere.[15]

Causes of decline

Habitat destruction is the main factor threatening the future of this iguana.[2][13] The iguanas nest in the sand of beaches that are a prime real-estate location on Little Cayman.[9][13]

Predation and injury to hatchlings by rats, to hatchlings and sub-adults by semi-domestic and feral cats, and killing of adults by roaming dogs are all placing severe pressure on the remaining wild population on both islands.[2]

Sister Island iguanas are all too frequently killed by vehicles.

Recovery efforts

A formal captive breeding program does not exist for this subspecies but it may be warranted for the Cayman Brac population.[16] As the population on Cayman Brac has not been found to be genetically distinct from the Little Cayman population; genetic diversity may be introduced from the Little Cayman population if it is needed.[16]

Captivity

The Lesser Caymans iguana is established in captivity, both in public and private collections.[8] Private individuals have established these animals in captive breeding programs (both purebred and occasionally mixed with either the blue iguana, Cuban iguana, and sometimes with both) minimizing the demand for wild-caught specimens for the pet trade.[8]

References

- "Cyclura nubila caymanensis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- Goetz, M. & Burton, F. J. (2012). "Cyclura nubila ssp. caymanensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved August 19, 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burton, Frederic (2004), "Taxonomic Status of the Grand Cayman Blue Iguana" (PDF), Caribbean Journal of Science, Caribbean Journal of Science, 8 (1), pp. 198–203, retrieved 2007-09-16

- "Green and Blue a world of difference to Iguanas", Cayman Net News, February 14, 2006, archived from the original on July 15, 2015, retrieved December 7, 2015

- Hollingsworth, Bradford D. (2004), "The Evolution of Iguanas: an Overview and a Checklist of Species", Iguanas: Biology and Conservation, University of California Press, p. 37, ISBN 978-0-520-23854-1

- Grant, Chapman (1940). "The Herpetology of the Cayman Islands". Bulletin Institute of Jamaican Science. 2: 1–55.

- Schwartz, Albert; Thomas, Richard (1975). Carnegie Museum of Natural History Special Publication No. 1 — A Check-list of West Indian Amphibians and Reptiles. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Carnegie Museum of Natural History. p. 113. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.123681.

- De Vosjoli, Phillipe (1992), The Green Iguana Manual, Contributions by David Blair, Escondido, California: Advanced Vivarium Systems, ISBN 1-882770-18-8

- Gerber, Glenn (2007-02-08), Lesser Caymans Iguana Cyclura nubila caymanensis, archived from the original on 2011-10-08

- Iverson, John; Smith, Geoffrey; Pieper, Lynne (2004), "Factors Affecting Long-Term Growth of the Allen Cays Rock Iguana in the Bahamas", Iguanas: Biology and Conservation, University of California Press, p. 184, ISBN 978-0-520-23854-1

- Martins, Emilia P.; Lacy, Kathryn (2004), "Behavior and Ecology of Rock Iguanas,I: Evidence for an Appeasement Display", Iguanas: Biology and Conservation, University of California Press, pp. 98–108, ISBN 978-0-520-23854-1

- Winker, Carol (2007-02-08), "Iguanas get royal attention", Cayman Net News

- Dorge, Ray (1996), "A Tour of the Grand Cayman Blue Iguana Captive-Breeding Facility", Reptiles: Guide to Keeping Reptiles and Amphibians, 4 (9): 40

- Blair, David (1983), "Dragons of the Cayman: Rock Iguanas Cling to their Islands", Oceans Magazine, 16 (1), pp. 31–33

- Alberts, Allison; Lemm, Jeffrey; Grant, Tandora; Jackintell, Lori (2004), "Testing the Utility of Headstarting as a Conservation Strategy for West Indian Iguanas", Iguanas: Biology and Conservation, University of California Press, p. 210, ISBN 978-0-520-23854-1

- "Iguana Population Struggling on Cayman Brac", Cayman Net News, 2005-07-01, archived from the original on 2009-09-09

| Wikispecies has information related to Cyclura nubila caymanensis |

Further reading

- Alberts, Allison C. (Editor), Carter, Ronald L. (Editor), Hayes, William K. (Editor), Martins, Emilia P. (2004). Iguanas : Biology and Conservation. University of California Press

- Grant, C. (1940). The herpetology of the Cayman Islands. Bulletin of the Institute of Jamaica Science Series

- Malone, C.L., Wheeler, T., Taylor, J.F. and Davis, S.K. (2000). Phylogeography of the Caribbean Rock Iguana (Cyclura): implications for conservation and insights on the biogeographic history of the West Indies.

- Schwartz, A. and M. Carey (1977). Systematics and evolution in the West Indian iguanid genus Cyclura. Fauna Curaçao Caribbean Islands.

External links

- Entry at Cyclura.com

- International Iguana Foundation Sister Isles Iguana

- Cayman Wildlife Connection

- Blue Iguana Recovery Program (B.I.R.P.)

- International Reptile Conservation Foundation

- World Wildlife Fund, ed. (2001). "Cayman Islands xeric scrub". WildWorld Ecoregion Profile. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 2010-03-08.

- Care of Cycluras in captivity