Workers' Party of Ireland

The Workers' Party (Irish: Páirtí na nOibrithe) is a Marxist–Leninist political party active in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.[2][3]

The Workers' Party Páirtí na nOibrithe | |

|---|---|

| |

| President | Michael Donnelly |

| Founded |

|

| Headquarters | 8 Cabra Road, Dublin 7, D07 T1W2, Ireland |

| Ideology | Communism Marxism–Leninism Irish republicanism Euroscepticism |

| Political position | Far-left |

| European affiliation | INITIATIVE |

| International affiliation | IMCWP ICS (Defunct) |

| Colours | Red, green |

| Local government in the Republic of Ireland | 1 / 949 |

| NI Assembly | 0 / 90 |

| NI Local Councils | 0 / 462 |

| Website | |

| www.workersparty.ie | |

It arose as the original Sinn Féin organisation founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffith, but took its current form in 1970 following a division within the party, in which it was the larger faction. This majority group continued under the same leadership as Sinn Féin (Gardiner Place) or Official Sinn Féin, while the breakaway group became known as Sinn Féin (Kevin Street) or Provisional Sinn Féin (giving rise to the contemporary party known as Sinn Féin). The party name was changed to Sinn Féin – The Workers' Party in 1977 and then to the Workers' Party in 1982.

Throughout its history, the party has been closely associated with the Official Irish Republican Army. Notable organisations that derived from it include Democratic Left and the Irish Republican Socialist Party. The party has one representative at local government level: Ted Tynan on Cork City Council.

Name

In the early to mid-1970s, Official Sinn Féin was sometimes called Sinn Féin (Gardiner Place) to distinguish it from the rival offshoot Provisional Sinn Féin, or Sinn Féin (Kevin Street). Gardiner Place had symbolic power as the headquarters of Sinn Féin for decades before the 1970 split. This sobriquet died out in the mid-1970s.

At its Ardfheis in January 1977, the Officials renamed themselves Sinn Féin – The Workers' Party. Their first seats in Dáil Éireann were won under this new name. A motion at the 1979 Ardfheis to remove the Sinn Féin prefix from the party name was narrowly defeated. The change finally came about three years later.[4]

In Northern Ireland, Sinn Féin was organised under the name Republican Clubs to avoid a ban on Sinn Féin candidates (introduced in 1964 under Northern Ireland's Emergency Powers Act), and the Officials continued to use this name after 1970.[5] The party later used the name The Workers' Party Republican Clubs. In 1982, both the northern and southern sections of the party became The Workers' Party.[6] The Workers' Party is sometimes referred to as the "Sticks" or "Stickies" because in the 1970s it used adhesive stickers for the Easter Lily emblem in its 1916 commemorations, whereas Provisional Sinn Féin used a pin for theirs.[7]

History

Origins

The modern origins of the party date from the early 1960s. After the failure of the then IRA's 1956–1962 "Border Campaign", the republican movement, with a new military and political leadership, undertook a complete reappraisal of its raison d'être.[4] Through the 1960s, some leading figures in the movement, such as Cathal Goulding, Seán Garland, Billy McMillen, Tomás Mac Giolla, moved steadily to the left, even to Marxism, as a result of their own reading and thinking and contacts with the Irish and international left. This angered more traditional republicans, who wanted to stick to the national question and armed struggle. Also involved in this debate was the Connolly Association.[8] This group's analysis saw the primary obstacle to Irish unity as the continuing division between the Protestant and Catholic working classes. This it attributed to the "divide and rule" policies of capitalism, whose interests were served by the working classes remaining divided. Military activity was seen as counterproductive, because its effect was to further entrench sectarian divisions. If the working classes could be united in class struggle to overthrow their common rulers, a 32-county socialist republic would be the inevitable outcome.[4]

However, this Marxist outlook became unpopular with many of the more traditionalist republicans, and the party/army leadership was criticised for failing to defend northern Catholic enclaves from loyalist attacks (these debates took place against the background of the violent beginning of what would become "the Troubles"). A growing minority within the rank-and-file wanted to maintain traditional militarist policies aimed at ending British rule in Northern Ireland.[4] An equally contentious issue involved whether to or not to continue with the policy of abstentionism, that is, the refusal of elected representatives to take their seats in British or Irish legislatures. A majority of the leadership favoured abandoning this policy.

A group consisting of Seán Mac Stiofáin, Dáithí Ó Conaill, Seamus Twomey, and others, established themselves as a "Provisional Army Council" in 1969 in anticipation of a contentious 1970 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis (delegate conference).[4] At the Ard Fheis, the leadership of Sinn Féin failed to attain the required two-thirds majority to change the party's position on abstentionism. The debate was charged with allegations of vote-rigging and expulsions. When the Ard Fheis went on to pass a vote of confidence in the official Army Council (which had already approved an end to the abstentionist policy), Ruairí Ó Brádaigh led the minority in a walk-out,[9] and went to a prearranged meeting in Parnell Square where they announced the establishment of a "caretaker" executive of Sinn Féin.[10] The dissident council became known as the "Provisional Army Council" and its party and military wing as Sinn Féin and the Provisional IRA, while those remaining became known as Official Sinn Féin and the Official IRA.[11] Official Sinn Féin, under the leadership of Tomás Mac Giolla, remained aligned to Goulding's Official IRA.[12]

The minority, those supportive of Seán Mac Stiofáin's "Provisional Army Council", endeavoured to achieve a united Ireland by force. As the Troubles escalated, this "Provisional Army Council" would come to command the loyalty of the IRA national organisation save for a few isolated instances (that of the IRA Company of the Lower Falls Road, Belfast under the command of Billy McMillen and other small units in Derry, Newry, Dublin and Wicklow); eventually the media came to characterise the Provisionals simply as "the IRA".

A key factor in the split was the desire of those who became the Provisionals to make military action the key object of the organisation, rather than a simple rejection of leftism.[13][14]

In 1977 Official Sinn Féin ratified the party's new name: Sinn Féin The Workers' Party without dissension.[15] According to Richard Sinnott, this "symbolism" was completed in April 1982 when the party became simply the Workers' Party.[16]

Political development

Although the Official IRA became drawn into the spiralling violence of the early period of conflict in Northern Ireland, it gradually reduced its military campaign against the United Kingdom's armed presence in Northern Ireland, declaring a permanent ceasefire in May 1972. Following this, the movement's political development increased rapidly throughout the 1970s.[4]

On the national question, the Officials saw the struggle against religious sectarianism and bigotry as their primary task. The party's strategy stemmed from the "stages theory": firstly, working-class unity within Northern Ireland had to be achieved, followed by the establishment of a united Ireland, and finally a socialist society would be created in Ireland.[17]

In 1977 the party published and accepted as policy a document called the Irish Industrial Revolution.[18] Written by Eoghan Harris and Eamon Smullen,[4] it outlined the party's economic stance and declared that the ongoing violence in Northern Ireland was "distracting working class attention from the class struggle to a mythical national question". The policy document used Marxist terminology: it identified US imperialism as the now-dominant political and economic force in the southern state and attacked the failure of the national bourgeoisie to develop Ireland as a modern economic power.[19]

Official Sinn Féin gravitated towards Marxism-Leninism and became fiercely critical of the physical force Irish republicanism still espoused by Provisional Sinn Féin. Its new approach to the Northern conflict was typified by the slogan it would adopt: "Peace, Democracy, Class Politics". It aimed to replace sectarian politics with a class struggle which would unite Catholic and Protestant workers. The slogan's echo of Vladimir Lenin's "Peace, Bread, Land" was indicative of the party's new source of inspiration. Official Sinn Féin also built up fraternal relations with the USSR and with socialist, workers' and communist parties around the world.[4]

Throughout the 1980s the party came to staunchly oppose republican political violence, controversially to the point of recommending cooperating with British security forces. They were one of the few organisations on the left of Irish politics to oppose the INLA/Provisional IRA 1981 Irish hunger strike.[4]

The Workers' Party (especially the faction around Harris) strongly criticised traditional Irish republicanism, causing some of its critics such as Vincent Browne and Paddy Prendeville to accuse it of having an attitude to Northern Ireland that was close to Ulster unionism.[20][21]

IRSP/INLA split and feud

In 1974 the Official Republican Movement split over the ceasefire and the direction of the organisation. This led to the formation of the Irish Republican Socialist Party (IRSP) with Seamus Costello (whom the Official IRA had expelled) as its chairperson. Also formed on the same day was IRSP's paramilitary wing, the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA). A number of tit-for-tat killings occurred in a subsequent feud until a truce was agreed in 1977.[22]

The Ned Stapleton Cumann inside RTÉ

Part of the party's plan to gain influence in the Republic of Ireland was the formation and maintenance of a secret branch (cumann), the Ned Stapleton Cumann, inside Ireland's national broadcaster RTÉ. Centred around the leadership of Eoghan Harris, the members were all employees of RTÉ and many of them were journalists. Members included Charlie Bird, John Caden and Marian Finucane. Úna Claffey was considered to be aligned with the Cumann. The branch started in the early 1970s and continued to operate in secrecy[23] until the Worker's Party broke apart in the early 1990s as the Soviet Union collapsed (1991) and likewise the Worker's Party saw a major split with the formation of the Democratic Left (1992). Remaining undetected was fundamental to the existence of the Cumann, as officially RTÉ reporters were not allowed to have party-political affiliations, in order to appear objective as journalists. The Cumann was influential within RTÉ, and used its position to shape the output of RTÉ programming; they pushed for narratives which reflected the official Sinn Féin/Worker's Party outlook, particularly in relation to the Provisional IRA.[24][25]

One programme impacted by the Cumann, Today Tonight, aired 4 nights a week and focused on investigative journalism. Although not directly involved with the show, the Cumann members ensured that SFWP members regularly appeared on the programme without having to acknowledge their membership. The Cumann was also able to influence one of RTÉ's flagship shows The Late Late Show, and placed SWFP activists into the show's studio audience, a studio audience who often took part in discussions on the show.[24]

During 1981 Irish hunger strike the Cumann was deeply annoyed by the positive coverage that the hunger strikers (such as Bobby Sands) began to receive, as they were aligned with the Provisionals. In response, they produced pieces which focused on the victims of violence by the Provisional IRA in Northern Ireland.[24]

The 1992 split

In early 1992, following a failed attempt to change the organisation's constitution, six of the party's seven TDs, its MEP, numerous councillors and a significant minority of its membership broke off to form Democratic Left, a party which later merged with the Labour Party in 1999.

The reasons for the split were twofold. Firstly, a faction led by Proinsias De Rossa wanted to move the party towards an acceptance of free-market economics.[26] Following the collapse of communism in eastern Europe, they felt that the Workers' Party's Marxist stance was now an obstacle to winning support at the polls. Secondly, media accusations had once again surfaced regarding the continued existence of the Official IRA which, it was alleged, remained armed and involved in fund-raising robberies, money laundering and other forms of criminality.[27]

De Rossa and his supporters sought to distance themselves from alleged paramilitary activity at a special Árd Fheis held at Dún Laoghaire on 15 February 1992. A motion proposed by De Rossa and General Secretary Des Geraghty sought to stand down the existing membership, elect an 11-member provisional executive council and make several other significant changes in party structures was defeated. The motion to "reconstitute" the party achieved the support of 61% of delegates. However, this was short of the two-thirds majority needed to change the Workers' Party constitution. The Workers' Party later claimed that there was vote rigging by the supporters of the De Rossa motion.[28] As a result of the conference's failure to adopt the motion, De Rossa and his supporters split from the organisation and established a new party which was temporarily known as "New Agenda" before the permanent name of "Democratic Left" was adopted.[29] In the South the rump of the party was left with seven councillors and one TD.

In the North, before the 1992 split, the party had four councillors – Tom French stayed with the party, Gerry Cullen (Dungannon) and Seamus Lynch (Belfast) joined New Agenda/Democratic Left, and David Kettyles ran in subsequent elections in Fermanagh as an Independent or Progressive Socialist.[30]

While the majority of public representatives left with De Rossa, many rank-and-file members remained in the Workers' Party. Many of these regarded those who broke away as careerists and social democrats who had taken flight after the collapse of the Soviet Union and denounced those who left as 'liquidators'.[31] Marian Donnelly replaced De Rossa as president from 1992 to 1994. Tom French became president in 1994, and served for four years until Sean Garland was elected president in 1998. Garland retired as president in May 2008, and was replaced by Mick Finnegan who served until September 2014, being replaced by Michael Donnelly[32][33]

A further minor split occurred when a number of members left and established a group called Republican Left; many of these went on to join the Irish Socialist Network. Another split occurred in 1998, after a number of former OIRA members in Newry and Belfast,[34] who had been expelled, formed a group called the Official Republican Movement,[35] which announced in 2010 that it had decommissioned its weapons.[36]

The party today

The Workers' Party has struggled since the early nineties to rejuvenate its fortunes in both Irish jurisdictions. The Workers' Party maintains a youth wing, Workers' Party Youth, and a Women's Committee. It also has offices in Dublin, Belfast, Cork and Waterford. Apart from its political work at home in Ireland, it has sent numerous party delegations to international gatherings of communist and socialist parties.[4]

The party supported an independent anti-sectarian candidate, John Gilliland, in the 2004 European elections in Northern Ireland.[37]

Waterford City remained a holdout for the party in the 1990s and early 2000s. In the 1997 Irish general election Martin O'Regan narrowly failed to secure a seat in the Waterford constituency.[38] However, in February 2008, John Halligan of Waterford resigned from the party when it refused to drop its opposition to service charges.[39] He was later elected a TD for Waterford in the 2011 general election. The party's sole remaining councillor in Waterford lost his seat in the 2014 local elections.

Michael Donnelly, a Galway-based university lecturer, was elected as the party President at the party's Ard Fheis on 27 September 2014 to replace Mick Finnegan who had announced his decision to retire from the position after six years.[40]

The Workers' Party called for a No vote against the Treaty of Lisbon in both the June 2008 referendum, in which the proposal was defeated, and the October 2009 referendum, in which the proposal was approved.[41] It was the only left-wing party to campaign for a No vote in the 2013 Seanad Abolition referendum. It called for a Yes vote in the marriage equality referendum in 2015. The party supported Brexit in the 2016 referendum.[42]

The Workers' Party has undergone a revival in the Dublin area since 2014. Éilis Ryan, an independent Councillor for the North Inner City ward of Dublin City Council, joined the Workers' Party in 2015.

The party has been heavily involved in campaigning for public housing and renters' rights as a response to the ongoing housing crisis in Ireland. In 2016 the party published Solidarity Housing, a public housing policy that proposed a cost-rental housing model for Ireland.[43][44] Later that year a Workers' Party motion for 100% mixed-income public housing on the publicly owned O’Devaney Gardens site in the north inner city was passed by Dublin City Councillors, but was later overturned after an intervention by then Minister for Housing Simon Coveney.[45]

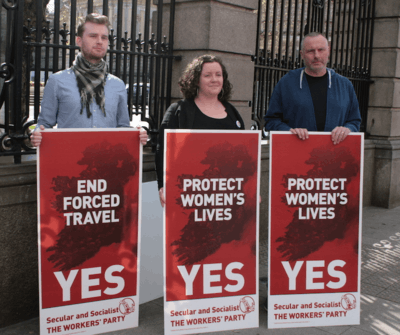

The party retains a strong tradition of secularism. In April 2017 Councillor Éilis Ryan organised a demonstration against the proposed control of the new National Maternity Hospital by the Sister of Charity.[46] The Workers' Party also campaigned for a yes vote in the referendum to repeal the 8th amendment in May 2018, having been the only party in the Dáil to oppose the introduction of the 8th amendment in 1983.[47]

Electoral performance

Republic of Ireland

The Workers' Party made its electoral breakthrough in 1981 when Joe Sherlock won a seat in Cork East. It increased this to three seats in 1982 and to four seats in 1987. The Workers' Party had its best performance at the polls in 1989 when it won seven seats in the general election and party president Proinsias De Rossa won a seat in Dublin in the European election held on the same day, sitting with the communist Left Unity group.[4]

Following the split of 1992, Tomás Mac Giolla, a TD in the Dublin West constituency and President of the party for most of the previous 30 years, was the only member of the Dáil parliamentary party not to side with the new Democratic Left. Mac Giolla lost his seat in the general election later that year, and no TD has been elected for the party since then. However, at local authority level, the Workers' Party maintained elected representation on Dublin, Cork and Waterford corporations in the aftermath of the split, and Mac Giolla was elected Lord Mayor of Dublin in 1993.

Outside of the south-east, the Workers' Party retains active branches in various areas of the Republic, including Dublin, Cork, County Meath[48] and County Louth. In the 1999 local elections, it lost all of its seats in Dublin and Cork and only managed to retain three seats in Waterford City. Further electoral setbacks and a minor split left the party after the 2004 local elections, with only two councillors, both in Waterford.

The party fielded twelve candidates in the 2009 local elections.[49] The party ran Malachy Steenson in the Dublin Central by-election on the same date.[50] Ted Tynan was elected to Cork City Council in the Cork City North East ward.[51] Davy Walsh retained his seat in Waterford City Council.[52] In the 2014 local elections Tynan retained his seat; however Walsh lost his, following major boundary changes resulting from the merging of Waterford City and County councils. In January 2015, Independent councillor Éilis Ryan on Dublin City Council joined the party.[53]

In the 2011 general election the Workers' Party ran six candidates, without success.[54] In the 2016 general election, the party ran five candidates, again without success.

Dáil Éireann elections

| Election | Seats won | ± | Position | First Pref votes | % | Government | Leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1973 as SF |

0 / 144 |

4th | 15,366 | 1.1% | No Seats | Tomás Mac Giolla | |

| 1977 as SFWP |

0 / 148 |

4th | 27,209 | 1.7% | No Seats | Tomás Mac Giolla | |

| 1981 as SFWP |

1 / 166 |

5th | 29,561 | 1.7% | Opposition (Abstained in formation vote on minority FG/Lab government) |

Tomás Mac Giolla | |

| Feb 1982 as SFWP |

3 / 166 |

4th | 38,088 | 2.3% | Opposition (Supported minority FF government) |

Tomás Mac Giolla | |

| Nov 1982 | 2 / 166 |

4th | 54,888 | 3.3% | Opposition | Tomás Mac Giolla | |

| 1987 | 4 / 166 |

5th | 67,273 | 3.8% | Opposition | Tomás Mac Giolla | |

| 1989 | 7 / 166 |

4th | 82,263 | 5.0% | Opposition | Proinsias De Rossa | |

| 1992 | 0 / 166 |

8th | 11,533 | 0.7% | No Seats | Tomás Mac Giolla | |

| 1997 | 0 / 166 |

11th | 7,808 | 0.4% | No Seats | Tom French | |

| 2002 | 0 / 166 |

9th | 4,012 | 0.2% | No Seats | Seán Garland | |

| 2007 | 0 / 166 |

9th | 3,026 | 0.1% | No Seats | Seán Garland | |

| 2011 | 0 / 166 |

10th | 3,056 | 0.1% | No Seats | Mick Finnegan | |

| 2016 | 0 / 158 |

11th | 3,242 | 0.2% | No Seats | Michael Donnelly | |

| 2020 | 0 / 158 |

14th | 1,195 | 0.1% | No Seats | Michael Donnelly |

Northern Ireland

The party gained ten seats at the 1973 Northern Irish local elections.[55] Four years later, in May 1977, this had dropped to six council seats and 2.6% of the vote.[56] One of their best results was when Tom French polled 19% in the 1986 Upper Bann by-election, although no other candidates stood against the sitting MP and a year later, when other parties contested the constituency, he only polled 4.7% of the vote.[57]

Three councillors left the party during the split in 1992. Davy Kettyles became an independent 'Progressive Socialist'[58] while Gerry Cullen in Dungannon and the Workers' Party northern chairman, Seamus Lynch in Belfast, joined Democratic Left.[59] The party held on to its one council seat in the 1993 local elections with Peter Smyth retaining the seat that had been held by Tom French in Craigavon.[60] This was lost in 1997,[61] leaving them without elected representation in Northern Ireland.

The party performed poorly in the March 2007 Assembly election; it won no seats, and in its best result in Belfast West, it gained 1.26% of the vote. The party did not field any candidates at the 2010 Westminster general election. In the 2011 Assembly election the Workers' Party ran in four constituencies, securing 586 first-preference votes (1.7%) in Belfast West and 332 (1%) in Belfast North.

The party contested the Westminster general election in May 2015, standing parliamentary candidates in Northern Ireland for the first time in ten years. It fielded five candidates and secured 2,724 votes, with Gemma Weir picking up 919 votes (2.3%) in Belfast North. The party did not field candidates in the December 2019 parliamentary election. In June 2020 the Ard Comhairle announced the Northern Ireland Business Committee and Belfast Constituency Council had split from the party by adopting "pro-unionist" policies.[62]

Publications

The party has published a number of newspapers throughout the years, with many of the theorists of the movement writing for these papers. After the 1970 split the Officials kept publishing the United Irishman (the traditional newspaper of the republican movement) monthly until May 1980. In 1973 the party launched a weekly paper The Irish People, which was focused on issues in the Republic of Ireland, there was also a The Northern People published in Belfast and focused on northern issues.[63] The party published an occasional international bulletin and a woman's magazine called Women's View. From 1989 to 1992 it produced a theoretical magazine called Making Sense. Other papers were produced such as Workers' Weekly.

The party produces a magazine, Look Left.[64] Originally conceived as a straightforward party paper, Look Left was relaunched as a more broad-left style publication in March 2010 but still bearing the emblem of the Workers' Party. It is distributed by party members and supporters and is also stocked by a number of retailers including Eason's and several radical/left-wing bookshops.[65]

Leaders

- Tomás Mac Giolla (1962–1988)[4]

- Proinsias De Rossa (1988–1992)

- Marian Donnelly (1992–1994)

- Tom French (1994–1998)

- Seán Garland (1998–2008)

- Mick Finnegan (2008–2014)

- Michael Donnelly (2014–present)

References

- The party emerged as the majority faction from a split in Sinn Féin in 1970, becoming known as Official Sinn Féin. In the Republic of Ireland, it renamed itself as Sinn Féin The Workers' Party in 1977. In Northern Ireland, it continued with the Republican Clubs name used by Sinn Féin to escape a 1964 ban, and later as Workers Party Republican Clubs. Both sections adopted the current name in 1982.

- "Register of Political Parties in Ireland". Houses of the Oireachtas. 23 November 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "NI Register of Political Parties". Electoral Commission. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- The Lost Revolution: The Story of the Official IRA and the Workers' Party, Brian Hanley and Scott Millar, ISBN 1-84488-120-2

- "CAIN". Cain.ulst.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- Ireland Today: Anatomy of a Changing State by Gemma Hussey, (1993) pgs. 172-3,194 .

- "The Lost Revolution: The Story of the Official IRA and the Workers' Party by Brian Hanley & Scott Millar, (2010) p. 151.

- Patterns of Betrayal: the flight from Socialism, Workers Party pamphlet, Repsol Ltd, Dublin, May 1992, page 74

- Sinn Féin: A Hundred Turbulent Years, Brian Feeney, O'Brien Press, Dublin 2002, ISBN 0-86278-695-9 pg. 250-1, Sinn Féin: A Century of Struggle, Parnell Publications, Mícheál MacDonncha, 2005, ISBN 0-9542946-2-9

- The Lost Revolution: The Story of The Official IRA and The Workers' Party, Brian Hanley & Scott Millar, Penguin Ireland (2009), ISBN 978-1-84488-120-8 p.146

- Richard Sinnott (1995), Irish Voters Decide: Voting behaviour in elections and referendums since 1918, Manchester University Press, p.59

- The Lost Revolution: The Story of the Official IRA and the Workers' Party, Brian Hanley and Scott Millar, ISBN 1-84488-120-2 pp. 286–336

- Henry McDonald, Gunsmoke and Mirrors, ISBN 978-0-7171-4298-9 p. 28

- Stephen Collins, The Power Game: Fianna Fáil since Lemass, ISBN 0-86278-588-X, p. 61

- The Lost Revolution: The Story of the Official IRA and the Workers' Party, Brian Hanley and Scott Millar, ISBN 1-84488-120-2 p. 336

- Irish voters decide: voting behaviour in elections and referendums since 1918, Richard Sinnott, Manchester University Press ND, 1995, ISBN 978-0-7190-4037-5 p.59

- See Swan,(pgs 303,330) and Brian Hanley and Scott Millar, The Lost Revolution, 2009 (pgs. 220, 256–7).

- http://cedarlounge.files.wordpress.com/2010/08/iir.pdf

- The Politics of Illusion: A Political History of the I.R.A. by Henry Patterson, (1997) and Official Irish Republicanism by Swan.

- The Longest War: Northern Ireland and the IRA by K. Kelley (1988) claimed that SFWP's attitude to the North was "indistinguishable in its structural form from that held by most Unionists" (pg. 270). See also Swan,Official Irish Republicanism, Chapter 8, and Politics in the Republic of Ireland by John Coakley and Michael Gallagher (2004), Pg. 28

- One of Harris' critics, Derry Kelleher, accused him of adopting the "Two Nations Theory" associated with Conor Cruise O'Brien; see Kelleher's book, Buried Alive in Ireland (2001), Greystones, Co. Wicklow: Justice Books.(pp. 252,294).

- English, Richard (2004) [2003]. "4: The Politics of Violence 1972-6". Armed Struggle: The History of the IRA. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 177ff. ISBN 9780195177534.

- Heaney, Mick (3 January 2012). "The battle for political supremacy in the newsroom". Irish Times. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- "The story of the revolutionaries working inside RTÉ". 30 August 2009. Archived from the original on 1 March 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- Corcoran, Farrel John (2004). RTÉ and the Globalisation of Irish Television.

- Proinsias De Rossa, 'The case for a new departure Making Sense March–April 1992

- BBC Spotlight programme, 'Sticking to their guns', June 1991

- Patterns of Betrayal, the Flight from Socialism, Workers Party, 1992, page 11

- The Lost Revolution: The Story of the Official IRA and the Workers' Party, Brian Hanley and Scott Millar, ISBN 1-84488-120-2, p. 588

- "The 1989 Local Government Elections, www.ark.ac.uk". Ark.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- Sean Garland, 'Beware of hidden agendas' Making Sense March–April 1992

- The Lost Revolution: The Story of the Official IRA and the Workers' Party, Brian Hanley and Scott Millar, ISBN 1-84488-120-2, p. 600

- "Keynote address of Party President Michael Donnelly". The Workers' Party of Ireland. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- "Official Republican Movement (ORM) – CAIN Archive". Cain.ulst.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- "Official Republican Movement". Irish Left Archive. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- McDonald, Henry (8 February 2010). "Rival Irish republican groups disarm". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- "Independent candidate: John Gilliland, www.bbc.co.uk". BBC News. 18 May 2004. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- "ElectionsIreland.org: 28th Dail – Waterford First Preference Votes". Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- "Workers' Party asks Halligan for his seat | Munster Express Online". Munster-express.ie. 22 February 2008. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- "http://workersparty.ie/2014/09/workers-partys-vibrant-ard-fheis/"

- Lisbon – A Treaty Too Far Workers' Party website

- "LEXIT: the socialist case for voting 'Leave'". The Workers' Party of Ireland. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- "Workers' Party publishes costed proposal for cross-subsidised public housing". The Workers' Party of Ireland. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- "Housing". The Workers' Party of Ireland. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- "Sinn Féin urged to publish legal advice ahead of vote to allow privatisation of O'Devaney Gardens land". The Workers' Party of Ireland. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- "'This is an insult to abuse survivors' – Protesters on the ownership of the new National Maternity Hospital". Irish Independent. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- "Workers' Party launches referendum campaign 35 years on from first opposing 8th amendment". The Workers' Party of Ireland. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- WP Meath branch http://www.wpi-meath.org/

- Local Elections Candidates Archived 9 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Press release Malachy Steenson candidate in Dublin Central". 7 April 2009. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- Ted Tynan Elected Cork Politics Website, 7 June 2009

- North Ward Waterford City Council – Election 2009 results RTÉ Website, 7 June 2009

- "Cllr. Éilis Ryan joins Workers' Party – The Workers' Party of Ireland". The Workers' Party of Ireland. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- "ElectionsIreland.org: Party Candidates". Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- "Local Government Elections 1973". Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- "Local Government Elections 1977". Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- Dr Nicholas Whyte. "Upper Bann results 1983–1995". Ark.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- "Fermanagh Council Elections 1993–2011". Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- "Courting Couple". JSTOR 25553420. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Local Government Elections 1993". Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- "Local Government Elections 1997". Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- Ryan, Eilis. "Statement by the Ard Comhairle of the Workers' Party on the decision to leave the Party by the Northern Ireland Business Committee and its supporters". The Workers' Party of Ireland. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Looking Left: The Irish People DCTV

- "Look Left Online". Look Left Online. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- "About us: Look Left". Lookleftonline.org. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

Bibliography

- Navigating the Zeitgeist: A Story of the Cold War, the New Left, Irish Republicanism and International Communism, Helena Sheehan, ISBN 978-1-58367-727-8

- My Life in the IRA, Michael Ryan, ISBN 978-1-781175187

- The Politics of Illusion: A Political History of the IRA, Henry Patterson, ISBN 1-897959-31-1

- Official Irish Republicanism, 1962 to 1972, Sean Swan, ISBN 1-4303-1934-8

- The Lost Revolution: The Story of the Official IRA and the Workers' Party, Brian Hanley and Scott Millar, ISBN 1-84488-120-2

External links

- Workers' Party official website

- Campaign to Stop the Extradition of Seán Garland to the United States

- Panorama – The Superdollar Plot – Transcript of BBC documentary

- BBC: Paramilitaries – Official IRA