Wirehead (science fiction)

Wirehead is a term first used in works of science fiction to refer to various kinds of interaction between human beings and technology, or to a person who makes use of such technology. In its most common usage, the "wirehead" concept refers to technologies involving electrical wiring that is implanted in or otherwise connected to a human brain and used to deliver safe amounts of electricity either to the whole brain or to more specific areas of the brain, often the so-called "pleasure centers" or reward circuitry.[2]

Though the concept of "wireheading" originated in science fiction, electrical brain stimulation and related technologies have long been studied in neuroscience and psychiatry and are routinely used in therapeutic and research settings. Usage of the science fiction term has since expanded to include these real-world applications.

In fiction

Literature

In Larry Niven's Known Space stories, a "wirehead" is someone who has been fitted with an electronic brain implant known as a "droud" in order to stimulate the pleasure centers of their brain. Wireheading is the most addictive habit known (Louis Wu is the only given example of a recovered addict), and wireheads usually die from neglecting their basic needs in favour of the ceaseless pleasure. Wireheading is so powerful and easy that it becomes an evolutionary pressure, selecting against that portion of humanity without self-control. A wirehead's death is central to Niven's Gil "the Arm" Hamilton story "Death by Ecstasy", published by Galaxy Magazine in 1969, and a main character in the book Ringworld Engineers is a former wirehead trying to quit.

Also in the Known Space universe, a device called a "tasp" which does not need a surgical implant (similar to transcranial magnetic stimulation) can be used to achieve similar goals: the pleasure center of a person's brain is found and remotely stimulated (considered a violation without seeking the person's consent beforehand). It is an important device in Niven's Ringworld novels.

Niven's stories explain wireheads by mentioning a study in which experimental rats had electrodes implanted at strategic locations in their brains, so that an applied current would induce a pleasant feeling. If the current could be obtained any time the rats pushed the lever, they would use it over and over, ignoring food and physical necessities until they died. Such experiments were actually conducted by James Olds and Peter Milner in the 1950s, first discovering the locations of such areas, and later showing the extremes to which rats would go to obtain the stimulus again.[3][4]

Mindkiller, a 1982 sci-fi novel by Spider Robinson set in the late 1980s, explores the social implications of technologies that manipulate the brain, beginning with wireheading, the use of electric current to stimulate the pleasure center of the brain in order to achieve a narcotic high.

In the Shaper/Mechanist stories by Bruce Sterling, "wirehead" is the Mechanist term for a human who has given up corporeal existence and become a computer simulation.

In The Terminal Man (1972) by Michael Crichton, forty electrodes are implanted into the brain of the character Harold Franklin "Harry" Benson to control his seizures. However, his pleasure center is also stimulated, and his body begins producing more seizures in order to receive the pleasurable sensation.[5]

Film and television

In the 1983 film Brainstorm, a wireless brain connection machine is made. A character named Hal Abramson abuses the device with a signal of neverending sexual pleasure.

In season three, episode 10, "Awakening" of the television series The Outer Limits, a neurologically impaired woman receives a brain implant to help her become more like a typical human.

In episode 41, "Zone Dancer" of the 1986 animated series The Centurions, the lead character Crystal Kane is accused of "Zone Dancing" (the series' term for computer hacking) and seen using a "droud" to interface her brain with computer networks in what is probably the first animated representation of cyberspace and virtual reality. The story, written by Michael Reaves, weaves a future noir tale of cyberpunk espionage, cloning, and private-eye procedural, all set in the universe of the animated series and makes copious references to William Gibson's Neuromancer. There is even a Zone Dancer named Gibson and, in what may be an homage to Larry Niven's Louis Wu, a cyberneticist named Dr. Wu.

The title character of the television series House is a physician who suffers from chronic pain. In the episode "Half-Wit", House seeks a medical procedure to stimulate the "pleasure center" of his brain.

Real-world examples

Though electrical brain stimulation is exaggerated to its logical extremity in science fiction tropes such as wireheading, the technology and its application for medical purposes do indeed exist in the real world. The application of electricity to the brains of animals in order to study brain function has been practiced for nearly a century. In 1924, Hans Berger succeeded in recording the first human electroencephalogram (EEG).[6] William Grey Walter wrote a paper in 1938 on the applications of electro-encephalography, the measurement of electrical activity in the brain using wires of different types.[7]

Wilder Penfield and Herbert Jasper used electrical stimulation of the human brain to find the places where their patients' seizures were coming from.[8] Dr. J. Lawrence Pool wrote "Effects of Electrical Stimulation of the Human Cerebellar Cortex" and described stimulation of a patient's brain.[9][10] In 1944, Reginald Bickford[11] is reported to have recorded the EEG of psychiatric patients who had had lobotomies.[12] After the 1949 Nobel Prize was awarded to António Egas Moniz for the procedure of lobotomy, a more precise method of destroying brain structures was pursued. In 1955, the placing of wires into a mentally ill patient was performed by Carl Wilhelm Sem-Jacobsen.[13] Stephen Sherwood also performed wire implantation.[14][15] In 1961, five patients had wires implanted to treat their mental illness and a precision leucotomy was performed for favorable results.[16][17]

Throughout the 1950s, many doctors continued to place wires or electrodes into the human brain.[18] They worked primarily on the brains of epileptic and psychiatric patients.[19][20][21][22] Robert Galbraith Heath placed electrodes in his subjects' brains in the 1950s to try to treat their mental illness and wrote several papers on his work of stimulating the various regions of the brain.[23] José Manuel Rodriguez Delgado also placed electrodes in his patients' brains. He called his inventions a "stimoceiver" and a "chemitrode".

By the 1980s, silver and copper electrodes had been found to be toxic to brain tissue.[24] Electrodes are encapsulated by fibrous growths as an inflammatory bodily response to a foreign object.[25]

- 1953: "Induced paroxysmal electrical activity in man recorded simultaneously through subcortical and scalp electrodes".[26]

- 1955: "Stimulation of the amygdaloid nucleus in a schizophrenic patient" by Robert Galbraith Heath.[27]

- 1963: "Electrical self-stimulation of the brain in man" by Robert Galbraith Heath.[28]

- 1972: A 24-year-old man with temporal lobe epilepsy, identified as patient "B-19". "He was permitted to wear the device for 3 hours at a time: on one occasion he stimulated his septal region 1,200 times, on another occasion 1,500 times, and on a third occasion 900 times. He protested each time the unit was taken from him, pleading to self-stimulate just a few more times..."[29][30]

- 1986: A 48-year-old woman with chronic pain. "The patient self-stimulated throughout the day, neglecting personal hygiene and family commitments."[29]

- 1986: To treat patients suffering from pain due to cancer, Dr. Young and Dr. Brechner made a study of electrical stimulation of the brain.[31]

- 2012: Cathy Hutchinson who is paralyzed had one hundred electrodes placed on the surface of her brain. With this brain–computer interface she is able to control a variety of devices.[32]

- 2013: A 49-year-old, right-handed woman had multiple electrodes placed in her brain for epilepsy. She reported an orgasmic ecstasy following the stimulation of the left hippocampus.[33]

- 2016: The New England Journal of Medicine described a growing do-it-yourself (DIY) medical engineering culture that includes DIY transcranial direct-current stimulation.[34]

- 2019: "Electronic implants studied for treatment of drug addiction". In China, doctors are treating addiction with brain implants aimed to stimulate the nucleus accumbens.[35]

See also

- Brain–computer interface

- Brain implant

- Brain stimulation reward (BSR)

- Click, an adult/erotic comic book series by Milo Manara

- Cortical stimulation mapping

- Deep brain stimulation (DBS)

- Experience machine

- Neuromodulation (medicine)

- Nucleus accumbens

- Pain and pleasure#Deep brain stimulation

- Pleasure center

- Responsive neurostimulation device (RNS)

- Transcranial pulsed ultrasound

External links

- 16 second YouTube graphic of an idealized working DBS

- Patient with wired brain At time index 1:24, a black and white YouTube video of Dr Robert Galbraith Heath and a patient with DBS wires embedded in their brain.

- Time Magazine February 2011

- The Perils of Deep Brain Stimulation for Depression. Author Danielle Egan. September 24, 2015.

- Brain Implants: Spinning the Trial Results to Protect the Product. Author Danielle Egan. January 14, 2018.

References

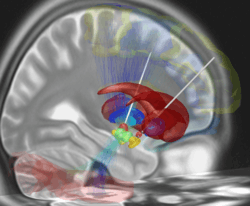

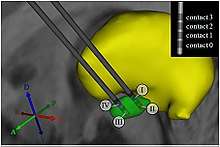

- Horn A, Kühn A (2015). "Lead-DBS: a toolbox for deep brain stimulation electrode localizations and visualizations". NeuroImage. 107: 127–35. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.12.002. PMID 25498389.

- "THE PLEASURE CENTRES" McGill University

- Olds J, Milner P (Dec 1954). "Positive reinforcement produced by electrical stimulation of septal area and other regions of rat brain". Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 47 (6): 419–27. doi:10.1037/h0058775. PMID 13233369.

- Olds J (1958). "Self-Stimulation of the Brain". Science. 127 (3294): 315–324. doi:10.1126/science.127.3294.315. PMID 13506579.

- Faria MA (2013). "Violence, mental illness, and the brain - A brief history of psychosurgery: Part 3 - From deep brain stimulation to amygdalotomy for violent behavior, seizures, and pathological aggression in humans". Surg Neurol Int. 4: 91. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.115162. PMC 3740620. PMID 23956934.

- Haas, LF (January 2003). "Hans Berger (1873-1941), Richard Caton (1842-1926), and electroencephalography". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 74 (1): 9. doi:10.1136/jnnp.74.1.9. PMC 1738204. PMID 12486257.

- Walter WG (1938). "Critical Review: The Technique and Application of Electro-Encephalography". J Neurol Psychiatry. 1 (4): 359–85. doi:10.1136/jnnp.1.4.359. PMC 1088109. PMID 21610936.

- "Stimulation of the human cortex and the experience of pain: Wilder Penfield's observations revisited" Laure Mazzola, Jean Isnard, Roland Peyron, François Mauguière . October 2011. doi.org/10.1093/brain/awr265

- Pool J. Lawrence (1943). "Effects of Electrical Stimulation of the Human Cerebellar Cortex". Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 2 (2): 203–204. doi:10.1097/00005072-194304000-00010.

- [Functional and Stereotactic Neurosurgery author E.I. Kandel. year 1989. Page 133. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-1-4613-0703-7#about]

- "In Memoriam: Reginald G. Bickford". American Journal of Electroneurodiagnostic Technology. 38 (3): 153–155. 1998. doi:10.1080/1086508X.1998.11079224.

- "Invasive Studies of the Human Epileptic Brain: Principles and Practice" edited by Samden D. Lhatoo, Philippe Kahane, Hans O. Luders. Page 10 of chapter "History of Invasive EEG".

- Sem-Jacobsen Carl W., Petersen Magnus C., Lazarte Jorge A., Dodge Henry W., Holman Colin B. (1955). "Electroencephalographic rhythms from the depths of the frontal lobe in 60 psychotic patients". Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 7 (2): 193–210. doi:10.1016/0013-4694(55)90035-3. PMID 13241382.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Sherwood Stephen L (2006). "Electrographic Depth Recordings from the Brains of Psychotics". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 96: 375–385. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1962.tb50130.x. PMID 13911750.

- "Depth-electrographic stimulation of the human brain and behavior" 1968

- Crow HJ, Cooper R, Phillips DG (1961). "Controlled multifocal frontal leucotomy for psychiatric illness". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 24 (4): 353–60. doi:10.1136/jnnp.24.4.353. PMC 495397. PMID 13882422.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Crow HJ, Cooper R, Phillips DG (1961). "Controlled multifocal frontal leucotomy for psychiatric illness". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 24 (4): 353–60. doi:10.1136/jnnp.24.4.353. PMC 495397. PMID 13882422.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Report to the people" by Governor C. Elmer Anderson. The Winthrop News. October 1st, 1953

- SEM-Jacobsen CW, Bickford RG, Petersen MC, Dodge HW Jr (1953). "Depth distribution of normal electroencephalographic rhythms". Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 28 (6): 156–61. PMID 13037901.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Monroe Russell R (1957). "Correlation of rhinencephalic electrograms with behavior". Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 9 (4): 623–642. doi:10.1016/0013-4694(57)90084-6. PMID 13480236.

- Lien J.B. (1960). "Depth-EEG of Two Schizophrenic Patients Under Marsilid-medication". European Neurology. 140: 133. doi:10.1159/000131248. PMID 13762050.

- "Exploration du cerveau humain par électrodes profondes". Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 12 (2): 490. 1960. doi:10.1016/0013-4694(60)90025-0.

- "For the mentally ill Pacemakers regulate the brain" Newspaper "The Spokesman Review" May 8, 1977.

- "Functional and Stereotactic Neurosurgery author E.I. Kandel. year 1989. Page 133."

- Review of Neuromodulation Techniques and Technological Limitations 5.1. Limitations of electrical electrodes page 4. November 2015. Authors Rabinder Henry, Martin Deckert, Velmathi Guruviah & Bertram Schmidt

- HEATH, RG; PEACOCK SM, Jr; MILLER W, Jr (1953). "Induced paroxysmal electrical activity in man recorded simultaneously through subcortical and scalp electrodes". Transactions of the American Neurological Association. 3 (78th Meeting): 247–50. PMID 13179226.

- Heath RG, Monroe RR, Mickle WA (1955). "Stimulation of the Amygdaloid Nucleus in a Schizophrenic Patient". American Journal of Psychiatry. 111 (11): 862–863. doi:10.1176/ajp.111.11.862. PMID 14361778.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Heath R.G. (1963). "Electrical self-stimulation of the brain in man". American Journal of Psychiatry. 120 (6): 571–577. doi:10.1176/ajp.120.6.571. PMID 14086435.

- "Erotic self-stimulation and brain implants". 2008-09-16.

- Moan C.E., Heath R.G. (1972). "Septal stimulation for the initiation of heterosexual activity in a homosexual male". Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 3: 23–30. doi:10.1016/0005-7916(72)90029-8.

- Young Ronald F (1986). "Electrical stimulation of the brain for relief of intractable pain due to cancer". Cancer. 57 (6): 1266–1272. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19860315)57:6<1266::AID-CNCR2820570634>3.0.CO;2-Q. PMID 3484665.

- "Paralyzed woman uses mind-control technology to operate robotic arm" by Scott Pelley CBS News May 16, 2012.

- Surbecka Werner, Bouthillierb Alain, Khoa Nguyenc Dang (2013). "Bilateral cortical representation of orgasmic ecstasy localized by depth electrodes". Epilepsy & Behavior Case Reports. 1: 62–65. doi:10.1016/j.ebcr.2013.03.002. PMC 4150648. PMID 25667829.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Greene JA (2016). "Do-It-Yourself Medical Devices — Technology and Empowerment in American Health Care". New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (4): 305–308. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1511363. PMID 26816009.

- "Electronic implants studied for treatment of drug addiction" CTV news. May 8, 2019. Author Erika Kinetz, The Associated Press.