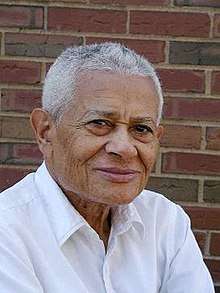

William Worthy

William Worthy, Jr. (July 7, 1921 – May 4, 2014) was an African-American journalist, civil rights activist, and dissident who pressed his right to travel regardless of U.S. State Department regulations.

William Worthy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 7, 1921 Boston, Massachusetts, US |

| Died | May 4, 2014 (aged 92) |

| Education | Bates College |

| Occupation | Journalist |

Biography

Early life

Worthy was born in Boston, Massachusetts,[1] as the son of a wealthy obstetrician. He graduated Boston Latin High School and received a B.A. degree in sociology from Bates College, Lewiston, Maine, in 1942. Worthy was a Nieman Fellow at Harvard University, class of 1957.

During World War II, Worthy was sentenced to one day in prison for dodging a physical examination for military service and failing to register at a conscientious objector's camp. In 1954, he voiced early opposition to American involvement in Vietnam after he visited Indo-China in 1953.

Right to travel controversies

In 1955, Worthy spent six weeks in Moscow, interviewing Nikita Khrushchev. He then traveled to China (1956–57), where he interviewed Zhou Enlai[2] and Cuba (1961), where he interviewed Fidel Castro, in violation of United States State Department travel regulations. At the time he entered China, Worthy was the first American reporter to visit and broadcast from there since the country's communist revolution in 1949.[3] While in China Worthy interviewed Samuel David Hawkins, an American soldier who was captured by the Chinese during the Korean War and defected to China in 1953.[4] His passport was seized upon his return to the U.S. from China and American lawyers Leonard Boudin and William Kunstler represented Worthy in an unsuccessful lawsuit seeking the return of his passport.

Without a passport, Worthy traveled to Cuba in the early days of Fidel Castro to report on the Cuban revolution. He was able to return to the U.S. in October 1961, showing his birth certificate and vaccination record at Miami Airport. However, in April 1962, he was summoned again to Miami, where he was tried and convicted for "returning to the United States without a valid passport." During this time, he was placed under surveillance by the FBI.[5] Worthy was again represented by Kunstler, who successfully persuaded a federal appeals court to overturn Worthy's conviction. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit found the restrictions unconstitutional. The court held that the government could not make it a crime under the Constitution to return home without a passport. Years later, Kunstler wrote in his autobiography, My Life As A Radical Lawyer, that the Worthy passport case was his "first experience arguing an issue about which I felt passionate," was the "first time I had ever invalidated a statute," and that success "confirmed my faith in the justice system."[6]

The Committee for the Freedom of William Worthy was formed in 1962 and was chaired by A. Philip Randolph and Bishop D. Ward Nichols. In a telegram to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, Randolph, James Farmer and James Forman noted that "white citizens who have come home without passports have never been prosecuted."[5] Folksinger Phil Ochs wrote a song called "The Ballad of William Worthy" about Worthy's trip to Cuba and its consequences.

He also travelled to North Vietnam, Indonesia, Cambodia and Iran. In 1981, the luggage of Worthy and two other journalists working with him, Terri Taylor and Randy Goodman, was seized by the FBI on their return from Iran; and they subsequently won a suit on Fourth Amendment grounds.[7]

Civil rights activist

Worthy was a civil rights activist and member of organisations such as the Fellowship of Reconciliation, the NAACP or the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, which advocated for a more balanced coverage of Cuba in the US media.

In 1947, he participated in the Journey of Reconciliation together with other prominent civil rights leaders, in which they challenged state segregation laws on public transport. The action inspired the later Freedom Riders.[5]

In the early 1960s he was an outspoken critic of the civil rights movement for not going far enough to achieve civil rights in housing and all areas of American life. William Worthy was one of the most important political allies of Malcolm X. In the late 1960s, Worthy organized a rent strike against a Catholic hospital in New York City that attempted to tear down Worthy's apartment building and turn it into a parking lot. Worthy later wrote about those experiences in a critically acclaimed book, The Rape of Our Neighborhoods, published in 1976.

Worthy was a reporter for the Baltimore Afro-American on and off from 1953 to 1980. He wrote a column and covered revolutions in Iran, Cuba, and China. Although a supporter of Malcolm X, he was critical of the Black Panthers in a 1969 column for "gratuitous and indiscriminate" 'Uncle Tom' attacks on virtually all the black bourgeoise" and their exposure to law enforcement due to "sloppy, inefficient, undisciplined organizational follow-through".[8]

Teaching

While Worthy continued to work in the field of journalism, in the 1970s he was appointed as head of the African American journalism program at Boston University. However, the BU president, John Silber, removed Worthy as head of the program after Worthy criticized the BU administration and he supported BU campus workers who were attempting to unionize. Following his BU appointment, Worthy taught journalism at UMass Boston. William Worthy and Michael Lindsey co-taught the first class in Critical Journalism in the country at the College of Public and Community service, a branch of UMass Boston. Noam Chomsky was a guest lecturer. William Worthy also taught at Howard University in the 1980s and 1990s and held the Anneberg Chair. During most of the 1990s until 2005, Worthy lived in Washington, D.C., where he served as a special assistant to the dean of the School of Communications at Howard U. and served on the board of directors of the National Whistleblower Center.

On February 22, 2008, the Nieman Foundation honored Worthy with the prestigious Louis M. Lyons Award.[9]

Death and legacy

Worthy died in Brewster, Massachusetts on May 4, 2014, at the age of 92, of Alzheimer's disease.[10]

The late psychologist Kenneth B. Clark said of Worthy: "The Bill Worthys of our society provide the moral fuel necessary to prevent the flickering conscience of our society from going out."

Footnotes

- Directory, Foreign Area Fellows - Volume 3. Foreign Area Fellowship Program. 1973. p. 14.

- "William Worthy, a Reporter Drawn to Forbidden Datelines, Dies at 92", New York Times, 2014-05-17, archived from the original on 2014-09-05, retrieved 2020-08-13

- The Press: Ban Broken. 07 January 1957.

- "Seven Out, Fourteen to Go!", Washington Afro-American, 1957-03-05, retrieved 2010-12-31

- Cold War Stories: William Worthy, the Right to Travel, and Afro-American Reporting on the Cuban Revolution (PDF), retrieved 2020-08-13

- Kunstler, William M., My Life As A Radical Lawyer, pp. 95-97 (Birch Lane Press 1994).

- McKibben, William E. (January 20, 1982). "3 Journalists To Sue FBI On Confiscation". The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved May 11, 2013.

- Militants being killed, jailed or forced to run. Worthy, William. Afro-American (1893-1988). Baltimore, Md. 08 Mar. 1969: 1.

- "Reclaiming a gallant voice - The Boston Globe". Boston.com. Retrieved 2014-05-13.

- "William Worthy, defiant journalist, dies at 92". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2014-05-13.

Works

- Our Disgrace in Indo-China. 1954.

- The Silent Slaughter: The Role Of The United States In The Indonesian Massacre. With Eric Norden, Andrew March, and Mark Lane. 1967.

- The Vanguard: A photographic essay on the Black Panthers. With Ruth-Marion Baruch and Parkle Jones. 1970.

- The Rape of Our Neighborhoods: And How Communities Are Resisting Take-Overs by Colleges, Hospitals, Churches, Businesses, and Public Agencies. 1976.

- Pampered Dictators and Neglected Cities: The Philippine Connection. 1978.

Further reading

- Robeson Taj Frazier, The East is Black: Cold War China in the Black Radical Imagination. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015.