William Hamilton Bird

William Hamilton Bird was an Irish musician who was active in India during Company rule. He was a pioneer in transcribing Indian music into western notation.[1]

Biography

Little is known of Bird´s early life. He appears to have come from Dublin, and by his own account he travelled to India in about 1770, remaining there until the 1790s. In 1789 he published in Calcutta (Kolkata) the work for which he is remembered, The Oriental Miscellany; being a collection of the most favourite airs of Hindoostan, compiled and adapted for the Harpsichord. There are about 30 pieces plus a flute sonata. The book was republished in Edinburgh (c. 1805 after Bird's death) with a slightly different selection of pieces.

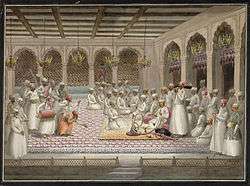

Bird's transcriptions can be seen in the broad context of European interest in "national" music, evidenced by publications of Irish and Scottish folk-song arrangements, such as "25 Scottish Songs" (Beethoven). They can also be seen in the context of a mingling of cultures in late 18th century India, as described, for example by the historian William Dalrymple.[2] The first edition of Bird's work was dedicated to Warren Hastings, the de facto Governor-General of India from 1773 to 1785. Hastings was interested in Indian music and Indian culture generally, he had promoted the first translation into English of the Bhagavad Gita. Other members of the British community who were interested in Indian music included:

- the judge Sir William Jones, who arrived in Calcutta in 1783. Best remembered as a philologist, his work "On the Musical Modes of the Hindus" was published posthumously in 1799.[1] He is known to have been involved in the transcription of song lyrics.[3]

- Sophia Plowden, an amateur musician who arrived in Calcutta in 1777 and also lived in the princely state of Lucknow. Plowden was one of the 250 subscribers to the "Oriental Airs".[4] She was a fan of the nautch girl Khanum Jan, one of the singers referenced in the work. She compiled a manuscript collection of airs which is now in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, and it appears that she was the source for some of the tunes published by Bird. She preserved lyrics as well as music, allowing the words to be restored for some of the music in Bird's book (which supplies Urdu titles but not lyrics).[5][6]

Sources

Bird appears to have collected his material from live performances of genres such as tappa (a mainly vocal tradition). Sometimes he indicates the singer associated with the piece and he appears to have had other, uncredited, collaborators such as Sophia Plowden.

The music came from an oral tradition, and we are not in a position to compare the transcriptions directly with the original versions. However, there is little doubt that in various ways, Bird's transcriptions are not faithful to the original versions:

- the tuning system of the main instrument featured, the harpsichord, does not give much scope for microtonality (shruti), a feature of Indian music.

- in the introduction to the Miscellany, Bird indicates that he struggled with Indian rhythms. When adapting the music to western taste, he avoided the more complicated rhythms, working with multiples of two or three beats per bar.[6]

- he added harmonies, whereas the Indian tradition is monophonic.

Live and recorded performances

The British label Signum Classics released a recording of the "Oriental Miscellany" in 2015 featuring the harpsichordist Jane Chapman.[6] It received international attention.[7] Jane Chapman had studied the music in a project supported by the Leverhulme Trust.[4] She played a 1722 Jacob Kirckman instrument in the Horniman Museum, London.[8] For the recording it was tuned in Vallotti temperament,[9] an alternative to equal temperament (the norm in Western music). The tuning gives the player more scope for an approximation of the modes (ragas) of Indian music.

Bird's work is also in the repertoire of other harpsichordists, for example Mahan Esfahani.[10]

See also

References

- Hewett, Ivan (2015). "The man who discovered Indian music". www.telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- Ziegler, P (2002). "A romance famous in the east (review of White Mughals)".

The tone of this early period of British life in India seemed instead to be about intermixing and impurity, a succession of unexpected and unplanned minglings of peoples and cultures and ideas.

- Woodfield, Ian (1994). "Collecting Indian Songs in Late 18th-Century Lucknow: Problems of Transcription". British Journal of Ethnomusicology. 3: 73–88. doi:10.1080/09681229408567227. JSTOR 3060807. accessed via JSTOR, subscription required

- "Jane Chapman: artist in residence at the Foyle Special Collections Library". King's College London. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Schofield, K (2018). "Sophia Plowden, Khanum Jan, and Hindustani airs".

- Kennicott (10 July 2015). "William Hamilton Bird: The Oriental Miscellany". Gramophone.

- Khurana (2015). "Of clefs and chords". The Indian Express.

- "Harpsichord". www.horniman.ac.uk. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- O´Regan, N. (2015). "The Oriental Miscellany". Early Music Review.

- "Programme note: 'El otro exotico' (concert given in Madrid in March 2018 in the series 'The East and Western Music')". Fundación Juan March (www.march.es). Retrieved 21 April 2018.