Texas divisionism

Texas divisionism is a mainly historical movement that advocates the division of the U.S. state of Texas into as many as five states, as statutorily permitted by a provision included in the resolution admitting the former Republic of Texas into the Union in 1845.[1]

Texas divisionists argue that the division of their state could be desirable because, as the second-largest and second most-populous state in the U.S., Texas is too large to be governed efficiently as one political unit, or that in several states Texans would gain more power at the federal level, particularly in the U.S. Senate, where each state elects two Senators, and by extension in the Electoral College, in which each state gets two electoral votes for their Senators in addition to an electoral vote for each Representative. However, others argue that division may be wastefully duplicative, requiring a new state government for each new state.

Federal constitutional process

Article IV, Section 3, of The United States Constitution expressly prohibits any other state from dividing up and forming smaller states without Congressional approval. The relevant clause says "New states may be admitted by the Congress into this union; but no new states shall be formed or erected within the jurisdiction of any other state; nor any state be formed by the junction of two or more states, or parts of states, without the consent of the legislatures of the states concerned as well as of the Congress".[2]

The Joint Resolution for Annexing Texas to the United States[1] , approved by Congress on March 1, 1845, states:

"Third -- New States of convenient size not exceeding four in number, in addition to said State of Texas and having sufficient population, may, hereafter by the consent of said State, be formed out of the territory thereof, which shall be entitled to admission under the provisions of the Federal Constitution; and such states as may be formed out of the territory lying south of thirty-six degrees thirty minutes north latitude, commonly known as the Missouri Compromise Line, shall be admitted into the Union, with or without slavery, as the people of each State, asking admission shall desire; and in such State or States as shall be formed out of said territory, north of said Missouri Compromise Line, slavery, or involuntary servitude (except for crime) shall be prohibited.”.

Proponents of creating new states argue that the resolution of 1845, a bill which passed both houses of Congress, stands as Congressional "pre-approval" under the terms of the Constitution for formation of such new states. Opponents argue that Constitution require future Congressional approval of any new states that are proposed to be formed from what is now the state of Texas.

Some constitutional scholars argue that any special "right" of Texas to create new states was ended by the secession of Texas in 1861, to join the Confederacy, and its subsequent, formal, readmission to the United States of America in 1865. Complicating this argument is an 1869 United States Supreme Court ruling, Texas v. White, holding that Texas remained part of the United States even during the Civil War.

Legislative efforts

The division of the state of Texas was frequently proposed in the early decades of Texan statehood, particularly in the decades immediately prior to and following the American Civil War.

Compromise of 1850 debates

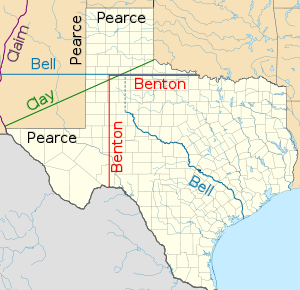

In the Compromise of 1850 debates, Senator John Bell proposed division into two southern states, with the assent of Texas, in February 1850. New Mexico would get all Texas land north of the 34th parallel north, including today's Texas Panhandle, while the area to the south, including the southeastern part of today's New Mexico, would be divided at the Colorado River of Texas into two Southern states, balancing the admission of California and New Mexico as free states.[3]

State of Lincoln

The State of Lincoln was proposed in 1869, to be carved out of the territory of Texas from the area south and west of the state's Colorado River. Unlike many other Texas division proposals of the Reconstruction period, this one was presented to Congress, but the state legislature did not take final action. [4]

State of Jefferson

A bill was introduced in the Texas legislature in 1915 to create a State of Jefferson, made up of the Texas Panhandle.[5]

Texlahoma

In 1935,[6] in response to what proponents felt was lack of state attention to road infrastructure, A. P. Sights proposed that 46 northern Texas counties and 23 western Oklahoma counties secede to form a new, roughly rectangular state called Texlahoma.[7]

Considerations

In 2009 Nate Silver wrote that a division could slightly help Republicans in the Senate while slightly hurting them in the Electoral College, concluding that there's not much rationale for either political party to support such a division.[8]

References

- "Joint Resolution for Annexing Texas to the United States Approved March 1, 1845". Texas State Libraries and Archive Commission.

- "Article IV | U.S. Constitution". Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- W. J. Spillman (January 1904). "ADJUSTMENT OF THE TEXAS BOUNDARY IN 1850". Quarterly of the Texas State Historical Association. 7.

- Division of Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online

- Division of Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online

- "Proposal Made to Create 49th State of Texlahoma". Hoosier State Chronicles: Indiana's Digital Historic Newspaper Program. The Daily Banner, Greencastle, Indiana (United Press). June 12, 1935. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- Trinklein, Mike (5 May 2010). "Lost States: Texlahoma". Mental Floss. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- Silver, Nate (24 April 2009). "Messing with Texas". FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

External links

- Snopes.com entry on the history of the proposal

- "Messing with Texas," a post on the FiveThirtyEight blog on the political implications of a hypothetical modern-day division of Texas