Szilágyi – Hunyadi Liga

Szilágyi – Hunyadi League[1][2][3][4][5] [6]was a movement led by Michael Szilágyi and his sister Erzsébet Szilágyi, created with the objective of putting Matthias Corvinus on the throne of the Kingdom of Hungary.

History

John Hunyadi died on 11 August 1456, less than three weeks after his greatest victory over the Ottomans in Belgrade.[7] John's elder son—Matthias's brother—Ladislaus became the head of the House of Hunyadi.[8][9] John's conflict with Ulrich II, Count of Celje ended with Ulrich's capture and assassination on 9 November.[10][11][12] Under duress, the King promised he would never take his revenge against the Hunyadis for Ulrich's killing.[13] However, the murder turned most barons—including Palatine Ladislaus Garai, Judge royal Ladislaus Pálóci, and Nicholas Újlaki, Voivode of Transylvania—against Ladislaus Hunyadi.[13] Taking advantage of their resentment, the King had the Hunyadi brothers imprisoned in Buda on 14 March 1457.[11][14] The royal council condemned them to death for high treason and Ladislaus Hunyadi was beheaded on 16 March.[15]

Matthias Corvinus was held in captivity in a small house in Buda.[13][16] His mother Erzsébet Szilágyi and her brother Michael Szilágyi founded Szilágyi – Hunyadi League, and staged a rebellion against the King and occupied large territories in the regions to the east of the river Tisza.[13][14] King Ladislaus fled to Vienna in mid-1457, and from Vienna to Prague in September, taking Matthias with him.[11][17][18] The civil war between the Szilágyi – Hunyadi League and the barons loyal to the monarch continued until the sudden death of the young King Ladislaus on 23 November 1457.[13] Hereafter the Hussite Regent of Bohemia—George of Poděbrady—held Matthias captive.[19]

Ladislaus V died childless in 1457.[20][21] His elder sister Anna and her husband, William III, Landgrave of Thuringia laid claim to his inheritance but received no support from the Estates.[20] The Diet of Hungary was convoked to Pest to elect a new king in January 1458.[22] Pope Calixtus III's legate Cardinal Juan Carvajal, who had been John Hunyadi's admirer, began openly campaigning for Matthias.[22][23]

The election of Matthias Corvinus as king was the only way of avoiding a protracted civil war.[22] Ladislaus Garai was the first baron to yield.[23] At a meeting with Michael Szilágyi and Erzsébet Szilágyi, he promised that he and his allies would promote Matthias's election, and Michael Szilágyi promised that his nephew would never seek vengeance for Ladislaus Hunyadi's execution.[22][23] They also agreed that Matthias would marry the Palatine's daughter Anna—his executed brother's bride.[22][23]

Michael Szilágyi arrived at the Diet with 15.000 troops, intimidating the barons who assembled in Buda.[11][22] Stirred up by Szilágyi, the noblemen gathered on the frozen River Danube and unanimously proclaimed the 14-year-old Matthias King on 24 January.[22][24][25] At the same time, the Diet elected Michael Szilágyi as Regent of the Kingdom of Hungary.[23][25]

Gallery

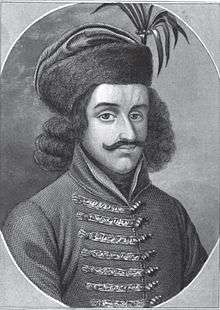

Matthias Corvinus as young monarch (after a contemporary miniature from the Corviniana collection of the British Museum)

Matthias Corvinus as young monarch (after a contemporary miniature from the Corviniana collection of the British Museum)

See also

- House of Szilágyi

References

- http://www.3szek.ro/load/cikk/77310/kiralyvalasztas_a_duna_jegen_1458_januar_24, 7 March 2015

- http://andrassygimi.hu/joomla/wrappers/koll_tortenet/pages/szilagyi.html, 7 March 2015

- http://index.hu/tudomany/tortenelem/2013/01/24/mi_tortent_a_duna_jegen_matyas_kirallyal/, 7 March 2015

- http://okpv.hu/viva-viva-rex-mathias/, 7 March 2015

- http://www.hir24.hu/tech-tud/2015/01/23/kiralyt-valasztottak-a-duna-jegen/, 7 March 2015

- http://www.rubicon.hu/magyar/oldalak/1458_oktober_8_matyas_kiraly_elfogatja_szilagyi_mihaly_kormanyzot/, 19 March 2015

- Engel 2001, pp. 280, 296.

- Kubinyi 2008, p. 25.

- Engel 2001, p. 296.

- Fine 1994, p. 569.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 61.

- Kubinyi 2008, p. 26.

- Engel 2001, p. 297.

- Kubinyi 2008, p. 27.

- Tanner 2009, p. 49.

- Tanner 2009, p. 50.

- Kubinyi 2008, p. 28.

- E. Kovács 1990, p. 30.

- Kubinyi 2008, p. 30.

- Kubinyi 2008, p. 29.

- Magaš 2007, p. 75.

- Engel 2001, p. 298.

- Kubinyi 2008, p. 31.

- Kubinyi 2008, pp. 31–32.

- Bartl et al. 2002, p. 51.

Sources

- Fraknói Vilmos: Michael Szilágyi, The uncle of King Matthias. Budapest, 1913.

- Kubinyi András (2008). Matthias Rex. Balassi Kiadó. ISBN 978-963-506-767-1.

- Engel Pál (2001). The Realm of St Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526. I.B. Tauris Publishers. ISBN 1-86064-061-3.

- John Van Antwerp Fine Jr. (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.

- Bryan Cartledge (2011). The Will to Survive: A History of Hungary. C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-1-84904-112-6.

- Tanner Marcus (2009). The Raven King: Matthias Corvinus and the Fate of his Lost Library. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15828-1.

- E. Kovács Péter (1990). Matthias Corvinus. Officina Nova. ISBN 963-7835-49-0.

- Magaš Branka (2007). Croatia Through History. SAQI. ISBN 978-0-86356-775-9.

- Bartl, Július; Čičaj, Viliam; Kohútova, Mária; Letz, Róbert; Segeš, Vladimír; Škvarna, Dušan (2002). Slovak History: Chronology & Lexicon. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, Slovenské Pedegogické Nakladatel'stvo. ISBN 0-86516-444-4.