Syrian Kurdistan

Syrian Kurdistan or Western Kurdistan (Kurdish: Rojavayê Kurdistanê) often shortened to Rojava, is the area of northern Syria regarded by many Kurds[1][2][3] and some regional experts as one of the four parts of a Greater Kurdistan.[4][5] In this conception, northern Syria (Western Kurdistan) is joined by southeastern Turkey (Northern Kurdistan), northern Iraq (Southern Kurdistan), and northwestern Iran (Eastern Kurdistan).[6] The term Syrian Kurdistan is often used in the context of Kurdish nationalism, which makes it a controversial concept among proponents of Syrian and Arab nationalism. There is ambiguity about its geographical extent, and the term has different meanings depending on context.

Demographic background

_1803.jpg)

Northern Syria is an ethnically diverse region. Kurds constitute one of several groups which have lived there since antiquity or the Middle Ages.[lower-alpha 1] The first Kurdish communitites constituted a minority and mostly consisted of nomads or military colonists.[8][7] During the Ottoman Empire (1516–1922), large Kurdish-speaking tribal groups both settled in and were deported to areas of northern Syria from Anatolia.[9] The last years of Ottoman rule witnessed extensive demographic changes in northern Syria as a result of the Assyrian Genocide and mass migrations.[10] During WWI, Kurdish tribes cooperated with the Turkish authorities in the massacres of Armenian and Assyrian Christians in Upper Mesopotamia, between 1914 and 1920, with further attacks on unarmed fleeing civilians conducted by local Arab militias.[11][12][13][14] Many Assyrians fled to Syria during the genocide and settled mainly in the Jazira area.[13][15][16]

Starting in 1926, the region saw another immigration of Kurds following the failure of the Sheikh Said rebellion against the Turkish authorities.[17] Waves of Kurds fled their homes in Turkey and settled in Syrian Al-Jazira Province, where they were granted citizenship by the authorities of the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon.[18] The number of Kurds settled in the Jazira province during the 1920's was estimated at 20,000[19] to 25,000 people[20], out of 100,000 inhabitants, with the remainder of the population being Christians (Syriac, Armenian, Assyrian) and Arabs.[19]

French mandate authorities gave the new Kurdish refugees considerable rights and encouraged minority autonomy as part of a divide and rule strategy and recruited heavily from the Kurds and other minority groups, such as Alawite and Druze, for its local armed forces.[21] French Mandate authorities encouraged their immigration and granted them Syrian citizenship.[22] The French official reports show the existence of at most 45 Kurdish villages in Jazira prior to 1927. A new wave of refugees arrived in 1929.[23] The mandatory authorities continued to encourage Kurdish immigration into Syria, and by 1939, the villages numbered between 700 and 800.[23] The French authorities themselves generally organized the settlement of the refugees. One of the most important of these plans was carried out in Upper Jazira in northeastern Syria where the French built new towns and villages (such as Qamishli) were built with the intention of housing the refugees considered to be "friendly". This has encouraged the non-Turkish minorities that were under Turkish pressure to leave their ancestral homes and property, they could find refuge and rebuild their lives in relative safety in neighboring Syria.[24] Consequently, the border areas in al-Hasakah Governorate started to have a Kurdish majority, while Arabs remained the majority in river plains and elsewhere. The population of the governorate reached 155,643 in 1949, including about 60,000 Kurds.[25] These continuous waves swelled the number of Kurds in the area who represented 37% of the Jazira population in a 1939 French authorities census.[26] In 1953, French geographers Fevret and Gibert estimated that out of the total 146,000 inhabitants of Jazira, agriculturalist Kurds made up 60,000 (41%), semi-sedentary and nomad Arabs 50,000 (34%), and a quarter of the population were Christians.[27]

Another demographic shift took place after Syria's independence, when 4000 farmer families from Raqqa were settled in Jazira to compensate them for their land inundated by the Tabqa Dam.[28] Mass migration also took place during the Syrian civil war. Accordingly, estimates as to the ethnic composition of northern Syria vary widely, ranging from claims about a Kurdish majority to claims about Kurds being a small minority.[29] In addition, the Kurdish population of Syria has been highly segmented due the different backgrounds and lifestyles of Kurdish groups.{{sfnp|Tejel|2009|p=9}

History

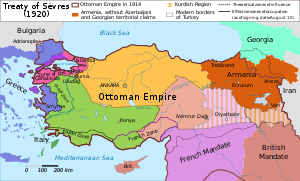

The concept of an independent "Kurdistan" as homeland of the Kurdish people has a long history,[30] but the extent of said territory has been disputed over time.[4] Although families of Kurdish ancestry have lived in territories which later became part of modern Syria for centuries (e.g., in Damascus, Aleppo, Hama),[8][7] Local Kurdish parties generally maintained ideologies which stayed in a firmly Syrian framework, and did not aspire to create a separate "Syrian Kurdistan".[31] In the 1920s, there were two separate demands for an autonomy of the areas with a Kurdish majority. One of Nouri Kandy, an influential Kurd from the Kurd Dagh, and another one of the Kurdish tribal leaders of the Barazi confederation. Both demands were not taken into consideration by the authorities of the French Mandate.[32]

The idea of Syrian territory being part of a distinct "Kurdistan" or "Syrian Kurdistan" gained more widespread support among Syrian Kurds in the 1980s and 1990s.[33] This development was fueled by the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) that strengthened Kurdish nationalist ideas in Syria, whereas local Kurdish parties had previously lacked "a clear political project" related to a Kurdish identity, partially due to political repression by the Syrian government.[34] Despite the role of the PKK in initially spreading the concept of "Syrian Kurdistan", the Democratic Union Party (PYD) (the Syrian "successor" of the PKK)[35] generally refrained from calling for the establishment of "Syrian Kurdistan".[9] As the PKK and PYD call for the removal of national borders in general, the two parties believed that there was no need for the creation of a separate "Syrian Kurdistan", as their internationalist project would allow for the "unification" of "Kurdistan" through indirect means.[2]

The idea of a "Syrian Kurdistan" gained even more relevance after the Syrian Civil War's start, as Kurdish-inhabited areas in northern Syria fell under the control of Kurdish-dominated factions. The PYD established an autonomous administration in northern Syria which it eventually began to call "Rojava" or "West Kurdistan".[2][5] By 2014, many local Kurds used this name synonymously to northeastern Syria.[1] As the PYD-led administration gained control over increasingly ethnically diverse areas, however, the use of "Rojava" for the merging proto-state was gradually reduced in official contexts.[36] Regardless, the polity continued to be called "Rojava" by locals and international observers,[37][38][39][40] with journalist Metin Gurcan noting that "the concept of Rojava [had become] a brand gaining global recognition" by 2019.[38]

See also

- Arabic Belt

Notes

- It is difficult to properly define early Kurds, as "Kurdish" was often used as a catch-all word for nomadic tribal groups west of Iran during antiquity and medieval times.[7]

References

- "Special Report: Amid Syria's violence, Kurds carve out autonomy". Reuters. 22 January 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- Kaya, Z. N., & Lowe, R. (2016). The curious question of the PYD-PKK relationship. In G. Stansfield, & M. Shareef (Eds.), The Kurdish question revisited (pp. 275–287). London: Hurst.

- Pinar Dinc (2020) The Kurdish Movement and the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria: An Alternative to the (Nation-)State Model?, Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies, 22:1, 47-67, DOI: 10.1080/19448953.2020.1715669

- Tejel (2009), p. 95.

- Kurdish Regional Self-rule Administration in Syria: A new Model of Statehood and its Status in International Law Compared to the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in Iraq

- Kurdish Awakening: Nation Building in a Fragmented Homeland, (2014), by Ofra Bengio, University of Texas Press

- Meri (2006), p. 445.

- Vanly (1992), p. 116.

- Tejel (2009), p. 123.

- Tejel (2009), pp. 9–10.

- Travis, Hannibal. Genocide in the Middle East: The Ottoman Empire, Iraq, and Sudan. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2010, 2007, pp. 237–77, 293–294.

- Hovannisian, Richard G., 2007. The Armenian Genocide: Cultural and Ethical Legacies. Accessed on 11 November 2014.

- R. S. Stafford (2006). The Tragedy of the Assyrians. pp. 24–25.

- Tejel, Jordi (2008). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society (PDF). pp. 25–29.

- "Ray J. Mouawad, Syria and Iraq – Repression Disappearing Christians of the Middle East". Middle East Forum. 2001. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- Bat Yeʼor (2002). Islam and Dhimmitude: Where Civilizations Collide. p. 162.

- Abu Fakhr, Saqr, 2013. As-Safir daily Newspaper, Beirut. in Arabic Christian Decline in the Middle East: A Historical View

- Dawn Chatty (2010). Displacement and Dispossession in the Modern Middle East. Cambridge University Press. pp. 230–232. ISBN 978-1-139-48693-4.

- Simpson, John Hope (1939). The Refugee Problem: Report of a Survey (First ed.). London: Oxford University Press. p. 458. ASIN B0006AOLOA.

- McDowell, David (2005). A Modern History of the Kurds (3. revised and upd. ed., repr. ed.). London [u.a.]: Tauris. p. 469. ISBN 1-85043-416-6.

- Yildiz, Kerim (2005). The Kurds in Syria : the forgotten people (1. publ. ed.). London [etc.]: Pluto Press, in association with Kurdish Human Rights Project. p. 25. ISBN 0745324991.

- Kreyenbroek, Philip G.; Sperl, Stefan (1992). The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview. London: Routledge. pp. 147. ISBN 0-415-07265-4.

- Tejel, Jordi (2009). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. London: Routledge. p. 144. ISBN 0-203-89211-9.

- Tachjian Vahé, The expulsion of non-Turkish ethnic and religious groups from Turkey to Syria during the 1920s and early 1930s, Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence, [online], published on: 5 March, 2009, accessed 09/12/2019, ISSN 1961-9898

- La Djezireh syrienne et son réveil économique. André Gibert, Maurice Févret, 1953. La Djezireh syrienne et son réveil économique. In: Revue de géographie de Lyon, vol. 28, n°1, 1953. pp. 1-15; doi : https://doi.org/10.3406/geoca.1953.1294 Accessed on 8 December 2019.

- Algun, S., 2011. Sectarianism in the Syrian Jazira: Community, land and violence in the memories of World War I and the French mandate (1915- 1939). Ph.D. Dissertation. Universiteit Utrecht, the Netherlands. Pages 11-12. Accessed on 8 December 2019.

- Fevret, Maurice; Gibert, André (1953). "La Djezireh syrienne et son réveil économique". Revue de géographie de Lyon (in French) (28): 1–15. Retrieved 2012-03-29.

- Allsopp & van Wilgenburg (2019), p. 27.

- Allsopp & van Wilgenburg (2019), pp. 7–16.

- Tejel (2009), p. 69.

- Tejel (2009), p. 86.

- Tejel (2009),p.27–28

- Tejel (2009), pp. 93–95.

- Tejel (2009), p. 93.

- Allsopp & van Wilgenburg (2019), p. 28.

- Allsopp & van Wilgenburg (2019), pp. 89, 151–152.

- "Turkey's military operation in Syria: All the latest updates". al Jazeera. 14 October 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- Metin Gurcan (7 November 2019). "Is the PKK worried by the YPG's growing popularity?". al-Monitor. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- "The Communist volunteers fighting the Turkish invasion of Syria". Morning Star. 31 October 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Nordsyrien: Warum ein Deutscher sein Leben für die Kurden riskiert" [Northern Syria: Why a German risks his life for the Kurds]. ARD (in German). 31 October 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

Works cited

- Allsopp, Harriet; van Wilgenburg, Wladimir (2019). The Kurds of Northern Syria. Volume 2: Governance, Diversity and Conflicts. London; New York City; etc.: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-8386-0445-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tejel, Jordi (2009). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. Abingdon-on-Thames, New York City: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-42440-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Meri, Josef W. (2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Volume 1: A - K. New York City, London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-96691-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vanly, Ismet Chériff (1992). "The Kurds in Syria and Lebanon". In Philip G. Kreyenbroek; Stefan Sperl (eds.). The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview. New York City, London: Routledge. pp. 112–134. ISBN 978-0-415-96691-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External Links

- Syria (Rojava or Western Kurdistan) by The Kurdish Project

- Examining the Experiment in Western Kurdistan by the LSE Middle East Centre

- The Emergence of Western Kurdistan and the Future of Syria by Robert Lowe